Florida Republicans are poised to adopt one of the nation’s most aggressive congressional maps, pressing forward with a proposal from Gov. Ron DeSantis that would most likely add four congressional districts for the party while eliminating three held by Democrats.

The map, which the Florida Senate approved by a party-line vote of 24 to 15 on Wednesday during a special session of the Legislature, was put forward by Mr. DeSantis after he vetoed a version approved in March by state legislators that would have added two Republican seats and subtracted one from the Democrats.

The new proposal would create 20 seats that favor Republicans and just eight that tilt toward Democrats, meaning that the G.O.P. would be likely to hold 71 percent of the seats. Former President Donald J. Trump carried Florida in 2020 with 51.2 percent of the vote.

The Florida map would erase some of the gains Democrats have made in this year’s national redistricting process. The 2022 map had been poised to be balanced between the two major parties for the first time in generations, with a nearly equal number of House districts that are expected to lean Democratic and Republican for the first time in more than 50 years.

The map would also serve as a high-profile, if possibly temporary, victory for Mr. DeSantis, who has emerged as one of the Republican Party’s leading figures and has not ruled out challenging Mr. Trump for the party’s 2024 presidential nomination. The Florida House is expected to pass the map on Thursday, and Mr. DeSantis is certain to sign it.

“I think they are good maps that will be able to be upheld,” said Joe Gruters, a Florida state senator who is the chairman of the state Republican Party.

If it is adopted into law, the Florida map would face legal challenges from Democrats, who clashed with Republicans on Tuesday over whether the proposal violated the state’s Constitution and the Voting Rights Act’s prohibition on racial gerrymandering.

What to Know About Redistricting

“It does appear to be politically motivated, and it does not take seriously the hard-working Black people in the state,” said Rosalind Osgood, a state senator from Broward County in South Florida.

Adam Kincaid, the executive director of the National Republican Redistricting Trust, the party’s main mapmaking organization, said that the proposed map complied with the state Constitution “while remaining faithful to the U.S. Constitution and the requirements of the Voting Rights Act.”

Some Democrats predicted that the DeSantis map would ultimately not pass legal muster — though any successful challenge would probably not arrive in time for the November elections. In addition to the Florida dispute, Democrats are locked in a court battle over a political gerrymander of their own in New York, where a judge last month invalidated Democratic-drawn maps.

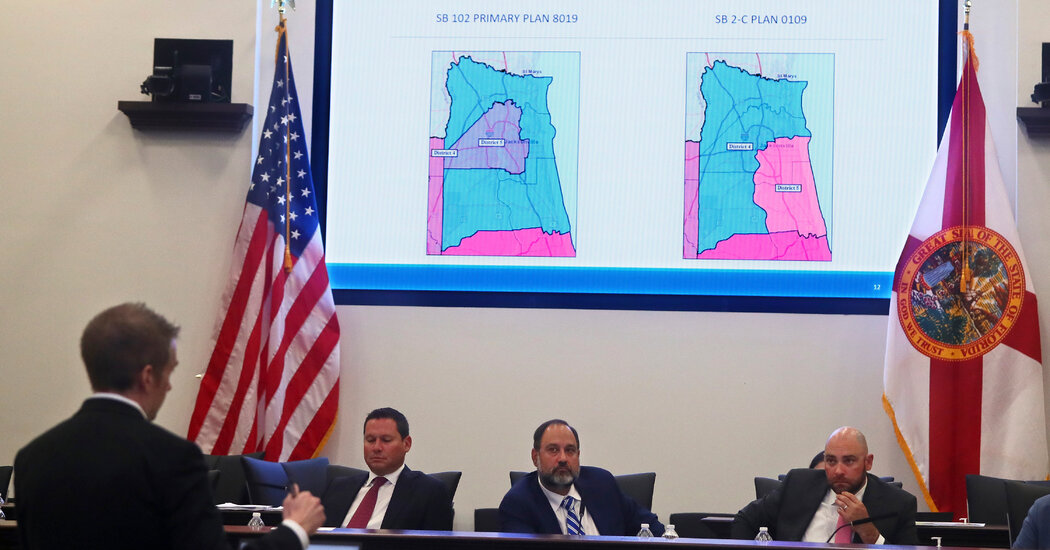

The Florida map would end the congressional career of Representative Al Lawson, a Black Democrat from Jacksonville, by carving up a district that stretches across North Florida to combine Black neighborhoods in Jacksonville and Tallahassee.

It would also eliminate an Orlando district held by Representative Val Demings, a Democrat, and pack Black voters from two districts in Tampa and St. Petersburg into one, creating a second district certain to be won by a Republican. Ms. Demings is vacating her seat to challenge Senator Marco Rubio, a Republican.

Mr. Lawson’s district has been held by a Black Democrat since 1993, when former Representative Corrine Brown first took office.

Mr. DeSantis’s map-drawer, Alex Kelly, said at a Florida Senate committee hearing on Tuesday that he could not draw a compact majority-Black district based in Jacksonville.

“I determined that was not possible to check all those boxes,” he said.

But Democrats argued that the map represented an unconstitutional racial gerrymander.

“Governor DeSantis is bullying the Legislature into drawing Republicans an illegitimate and illegal partisan advantage in the congressional map, and he’s doing it at the expense of Black voters in Florida,” Kelly Burton, the president of the National Democratic Redistricting Committee, said in an interview. “This blatant gerrymander will not go unchallenged.”

Democrats’ objections to the DeSantis map focused in part on a state constitutional amendment enacted by Florida voters in 2010 that set new standards for the redistricting process by requiring compact districts that did not favor one political party. A state court ordered Florida’s entire congressional map to be redrawn before the 2016 elections.

How U.S. Redistricting Works

What is redistricting? It’s the redrawing of the boundaries of congressional and state legislative districts. It happens every 10 years, after the census, to reflect changes in population.

Ellen Freidin, the leader of Fair Districts Now, a group that led the charge for the 2010 amendment, said Mr. DeSantis was disregarding the will of Florida voters.

“The governor has, rather than following the Fair Districts amendment, decided he is going to instruct his people to not follow the amendment and see if he can get away with it,” Ms. Freidin said. “This governor has made a unilateral decision to disregard the will of the 63 percent of the people who voted for these Fair Districts amendments and is simply ignoring what’s in the Florida Constitution.”

Mr. Kelly, who is the governor’s deputy chief of staff, told legislative Democrats that Florida’s current map is itself a violation of the 14th Amendment because it carves out specific districts to be represented by Black members of Congress.

Mr. Kelly told Democratic state senators repeatedly that he had not considered communities of interest, race or political data in drawing the governor’s proposed congressional districts. He said he did not know the political result of the map he had produced.

“I am unaware of the Black voting age population of District 14,” he said of the proposed district that would pack together Black voters from Tampa and St. Petersburg. “I was just drawing a district with nice, clean, compact lines.”

Democrats on the Florida Senate’s redistricting committee questioned Mr. Kelly’s explanation.

Randolph Bracy, a Democratic state senator from Orlando, asked if Mr. Kelly was under oath during his appearance before the committee. The committee’s Republican chairman, State Senator Ray Wesley Rodrigues, replied that Mr. Kelly was not. Mr. Rodrigues declined Mr. Bracy’s request to place Mr. Kelly under oath.

Mr. Bracy said Black voters in his district would go from being represented in Washington by Ms. Demings to being represented by Anthony Sabatini, a deeply conservative Republican state representative who is white.

“You’re saying you had no idea — this is the first time you were ever considering that point?” Mr. Bracy asked.

Mr. Kelly replied that he did not know the political implications of his proposed maps.

“It would have violated the law for me to go anywhere near an analysis like that,” he said. “I didn’t draw a single district in this map based on race.”