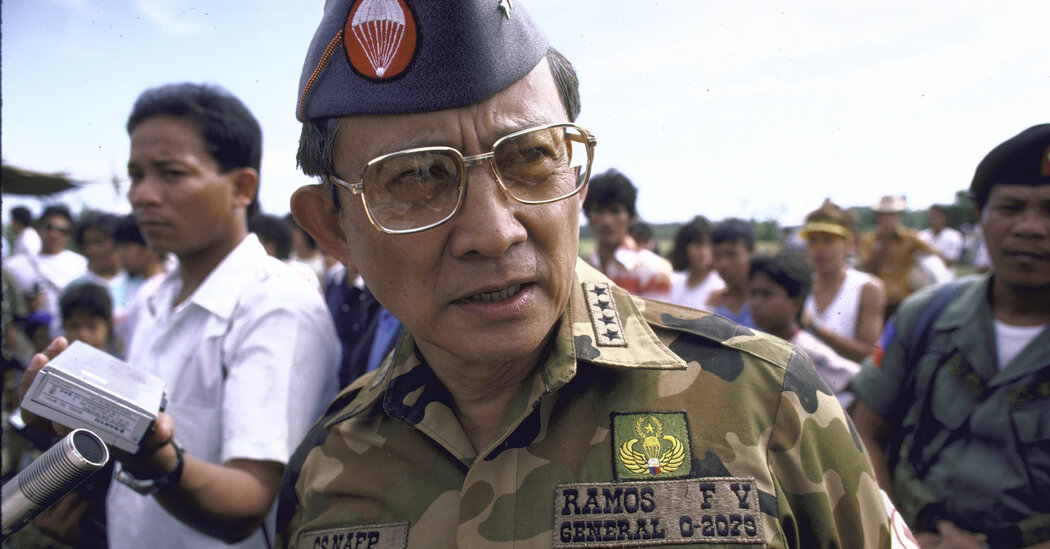

Fidel V. Ramos, a military leader who succeeded Corazon C. Aquino as president of the Philippines, and from 1992 to 1998 presided over robust economic growth, exceptional political stability and reconciliations with Communist insurgents and Muslim separatists, died on Sunday in Manila. He was 94.

The defense ministry confirmed his death in a statement Sunday.

A longtime aide, Norman Legaspi, told The Associated Press that Mr. Ramos died at the Makati Medical Center and that he had suffered from a heart condition and dementia.

In a nation battered by the corrupt dictatorship of Ferdinand E. Marcos, who was ousted in a popular uprising in 1986, Ms. Aquino and Mr. Ramos led a struggle, in back-to-back six-year terms under a banner of “People Power,” to re-establish democracy, reform a prostrate economy and make peace with extremists.

It was facile to say, as many Filipinos did, that Ms. Aquino reinstated democracy and that Mr. Ramos restored the economy. In fact, she began many economic policies that flourished under Mr. Ramos, and he successfully defended Ms. Aquino’s fragile democratic government against repeated military mutinies.

Mr. Ramos, a second cousin of President Marcos, was the scion of a patrician family steeped in public service. His father was an ambassador during World War II and a foreign minister in the Marcos regime. Mr. Ramos graduated from the United States Military Academy, served in the Korean War alongside American troops and commanded a Philippine contingent in the Vietnam War.

He was also a study in contradictions. Filipinos puzzled over the deeds and character of a Protestant who became president of a Roman Catholic country, of a hard-line general who brought about liberal economic, political and social changes in a nation exploited for centuries by Spanish and American colonialists, Japanese invaders and the infamous two-decade reign of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos.

Early in his career, Mr. Ramos was a Marcos loyalist who commanded a security force that committed human rights abuses and arrested thousands of dissidents, including Ms. Aquino’s husband, Senator Benigno S. Aquino Jr., who was imprisoned for years, exiled and then assassinated on the day of his return. Critics called Mr. Ramos a ruthless Marcos henchman.

But Mr. Ramos, who insisted he was only enforcing law and order, was later hailed as a national hero for making a moment-of-truth decision to break with President Marcos, sounding the death knell for his regime, and swearing allegiance to the Constitution and to Ms. Aquino. She named him armed forces chief and then defense minister, and later endorsed him for the presidency.

Narrowly elected in a plurality, Mr. Ramos took office vowing not to be a carbon copy of Ms. Aquino. “She has done her job, which is to establish political freedom,” he told The Far Eastern Economic Review. “But the second phase is to strengthen democracy. My priority is unifying the country.”

He reached peace agreements with two long-active guerrilla insurgencies, the Communist New People’s Army and the Muslim separatists of the Moro National Liberation Front, granting amnesty to thousands. He also purged the national police of 600 corrupt officers and cracked down on scores of warlords engaged in smuggling, drug-running and other crimes.

To revive the economy, he carried out reforms to encourage private enterprise, open trade and foreign investment. He traveled across Asia and the United States, meeting with government and business leaders to stress his nation’s stable political climate, declining inflation and favorable exchange rates. By some estimates, he generated $20 billion in new foreign investments in the Philippines.

He deregulated and privatized industries in an economy that had been dominated by a few large companies, overhauled the government’s inefficient tax system and encouraged family-planning practices to curb population growth. To improve unreliable electrical supplies, he reorganized the state power company, authorized new power plants and turned brownouts into a rarity.

National growth under Mr. Ramos rose from almost stagnant to nearly 6 percent a year, before sinking in an East Asian regional slump to 3 percent in his last year in office.

“The Philippines has proven to be a good model in the developing world to demonstrate that democracy and development are compatible,” Mr. Ramos told The New York Times in 1998. “Authoritarianism, while it promotes rapid growth initially, is not compatible with a free market system, which must be transparent and predictable.”

Fidel Valdez Ramos was born in Lingayen, north of the capital, Manila, on March 18, 1928, to Narciso and Angela Valdez Ramos. His father, a journalist, lawyer and congressman, was a wartime envoy to Taiwan and a Marcos foreign minister. One of Fidel’s sisters, Leticia Ramos Shahani, was a diplomat and Philippine senator.

After graduating from West Point in 1950, Mr. Ramos earned a master’s degree in civil engineering from the University of Illinois and other degrees in business administration and national defense from Philippine universities.

He married Amelita Martinez in 1954. She survives him, as do their four daughters, Angelita Ramos-Jones, Carolina Ramos-Sembrano, Cristina Ramos-Jalasco and Gloria Ramos. A fifth daughter, Josephine Ramos-Samartino, died in 2011.

After his Korean and Vietnam service, Mr. Ramos returned to a Philippines in the throes of protest against the Marcos regime. He joined the dictator’s inner circle, one of the “Rolex 12” advisers who received gold watches, and was named commander of the Philippine Constabulary, a national security force that dealt with terrorists.

Barred by law from seeking a third term in 1972, Mr. Marcos declared martial law, citing the threat of Communist and Muslim insurgencies. Ruling by decree, he curtailed civil liberties, closed Congress and arrested opponents, including Mr. Aquino, who was imprisoned for seven years and shot dead at the Manila airport when he returned from exile in 1983.

The murder catapulted his widow into the political spotlight. Three years later, in a snap election allowed by Mr. Marcos because he thought he could not lose, Ms. Aquino won the presidency. Mr. Marcos tried to steal it back by fomenting a military coup.

For Mr. Ramos, the armed forces chief, the moment of truth came on Feb. 22, 1986, when he had to choose whether to remain loyal to Marcos and his old military comrades, or to support Ms. Aquino.

Near midnight, his command decision went out to the troops nationwide: “The New Armed Forces of the Philippines stands behind the Government of President Aquino, having been elected and installed by the people. We must not betray our country and our people.”

Three days later, Mr. Marcos fled the Philippines.

Jason Gutierrez contributed reporting.