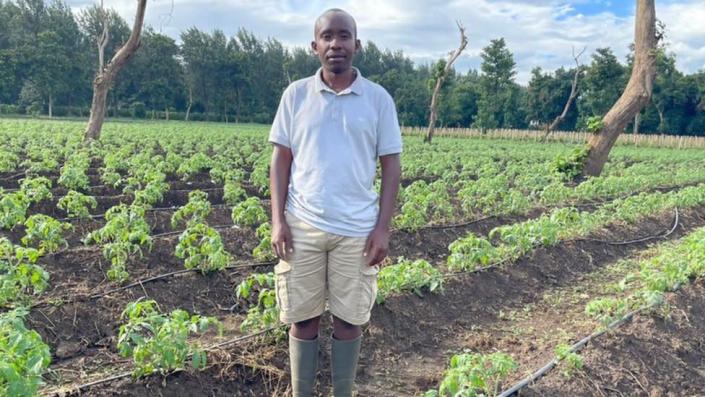

Under the beating Tanzanian sun, Lossim Lazzaro nervously looks over his farm.

He slowly pours livestock manure on his crops, in a last-ditch attempt to help them grow.

Mr Lazzaro owns five acres of land and was once a successful tomato farmer in the northern Arusha region. But now, like many others, he is battling to keep his business and crops alive, amid a global fertiliser shortage.

“It’s been difficult for me to get fertiliser in the market,” Mr Lazzaro says.

Fertiliser – the key ingredient needed to help crops grow – is in short supply across the world. Global prices have also sky-rocketed in part because of the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

“I used to buy fertiliser for about $25 (£20) per 50 kg bag in 2019,” Mr Lazzaro recalls.

“But the same bag now goes for almost double that price. It is extremely expensive for me.”

The amount of fertiliser available globally has almost halved, while the cost of some types of fertilizer have nearly tripled over the past 12 months, according to the United Nations.

That is having a knock-on effect in countries like Tanzania, where farmers are dependent on imported fertiliser.

“I ended up buying fertiliser from a local manufacturer but still I have to place an order months earlier due to the shortage,” Mr Lazzaro adds.

The crisis is fuelling fears of food scarcity.

Africa – which already uses the least amount of fertiliser per hectare in the world – is at high risk.

The short supply will inevitably impact crop yields, particularly for wheat which requires a lot of fertiliser and is essential for feeding millions.

The World Food Programme (WFP) has warned that the fertiliser shortage could push an additional seven million people into food scarcity.

They say that cereal production in 2022 will decline to about 38 million tonnes, from the previous year’s output of over 45 million tonnes.

Tanzania, like many other African countries, relies on fertiliser from Russia and China – the two leading global manufacturers.

Russia, which is under Western sanctions, produces large amounts of potash, ammonia and urea.

These are the three key ingredients needed to make chemical fertiliser. They helped to fuel the Green Revolution in the 1960s which tripled global grain production and helped to feed millions.

Russia exports around 20% of the world’s nitrogen fertilisers and combined with its sanctioned ally Belarus, 40% of the world’s exported potassium, according to data from Rabobank.

The cost of fertiliser was already high following the economic fallout of the Covid-19 pandemic. Now, the sanctions on Russia and Belarus, compounded with export controls in China, have made a bad situation worse.

The crisis has left many African countries, which are heavily dependent on foreign imports, scrambling to find solutions.

Demand for locally produced fertiliser is rising. Small-scale farmers in the north of Tanzania are now turning to places like Minjingu Mines and Fertilizer Ltd, one of the biggest fertiliser manufacturers in the country.

The company says it is experiencing a sudden increase in demand and is struggling to fill orders. But bosses say they are unable to increase their capacity due to heavy taxation.

“We don’t have a level playing ground compared to the importers,” said Tosky Hans, a director of Minjingu Mines and Fertilizer.

“Local manufacturers have to pay a lot of taxes, whereas the importers don’t,” he added.

Like many other countries, foreign investors are given subsidies in Tanzania to attract investment while local manufacturers pay set taxes.

Alliance for Green Revolution in Africa (Agra), a non-government organisation that promotes green solutions across the continent, says this is an opportunity for farmers to become more self-sufficient.

Vianey Rweyendela, country manager of Agra Tanzania, encourages farmers to unionise and form cooperatives. A move he says that could give them a voice on market prices.

“That will help them have bargaining power and fertiliser sold to them will be affordable,” argues Mr Rweyendela.

The richest man in Africa, Aliko Dangote, recently commissioned a fertiliser plant in Nigeria, which is expected to produce three million tonnes of urea fertiliser annually.

He believes, guaranteed supplies will make the difference.

“Ordering fertiliser and having it arrive has been a big challenge for farmers in Africa and they end up missing their planting season,” said Mr Dangote.

“With the launch of this plant, we shall ensure farmers get the nutrients early.”