A video of Giorgia Meloni, a right-wing politician who has become Italy’s new prime minister, accusing France of using a “colonial currency” to “exploit the resources” of African countries has been widely shared on social media.

There have been recent tensions between the two countries over how to deal with African migrants. Italy refused to allow a migrant rescue ship to dock, France accused the Italians of “unacceptable behaviour”.

The video clip shows Ms Meloni claiming that “50% of everything that Burkina Faso exports ends up in… the French treasury”.

On 19 November, Dutch commentator Eva Vlaardingerbroek tweeted the video, saying “I bet Emmanuel Macron now regrets to have picked a fight with Giorgia Meloni”. This got tens of thousands of retweets.

On 20 November, the Daily Mail wrote about the video clip with the headline: “Italy’s new firebrand PM launches blistering diatribe saying immigration from Africa would STOP if countries like France halted exploitation of continent’s valuable resources”.

But the video clip with Ms Meloni is actually from 2019 – long before she became prime minister – and her comments back then were wrong.

What did Giorgia Meloni claim?

The video is from an interview given on 19 January 2019 on the private Italian TV channel La 7, when Ms Meloni was an MP and leader of the right-wing party, Brothers of Italy.

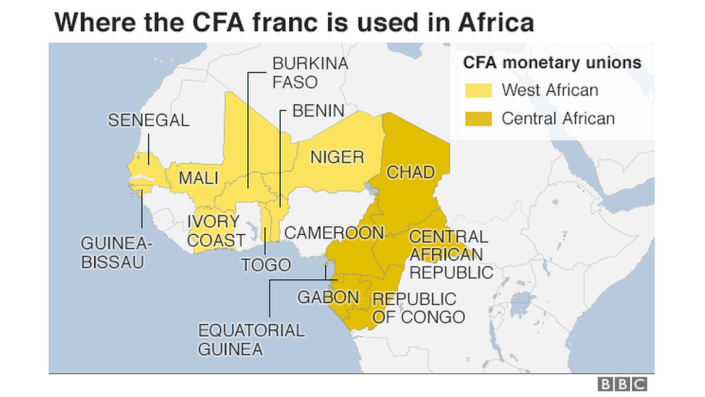

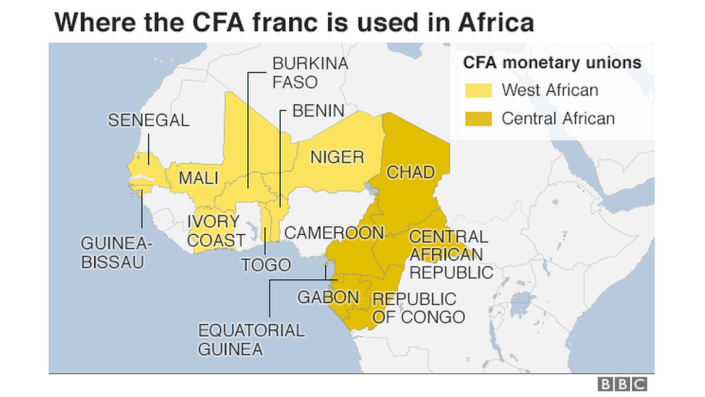

Ms Meloni holds up a CFA franc bank note, describing it as a “colonial currency” that France prints for 14 African countries which, she claims, it uses to “exploit the resources of these nations”.

She then holds up a picture of a child working in a gold mine in Burkina Faso and claims that “50% of everything that Burkina Faso exports ends up in… the French treasury”.

“The gold that this child goes down a tunnel to extract, mostly ends up in the coffers of the French state.”

The video clip ends with her saying “the solution is not to take Africans and bring them to Europe, the solution is to free Africa from certain Europeans who exploit it”.

We looked into a similar claim in 2019 when another Italian politician blamed France for impoverishing Africa and encouraging migration to Europe.

What is the evidence?

France does print currency – the CFA franc – for 14 African countries, including Burkina Faso. Participation in this currency is voluntary.

The currency was created by France in the late 1940s to serve as legal tender in its then-African colonies.

At the time Ms Meloni made her claim in 2019, France required African countries that used the CFA franc to deposit 50% of their foreign exchange reserves (not their exports) with the French treasury, in return for a guaranteed exchange rate with the Euro.

These countries were free to access these reserves at any time if they wanted to and France paid them interest while holding them (at 0.75%).

France didn’t “demand 50% of everything Burkina Faso exports” either.

According to World Bank data, France isn’t even among the top five destinations for Burkina Faso exports in total value, the leading export being gold. In 2020, it exported nearly 90% of its gold to Switzerland.

We asked Ms Meloni’s office if she still stands by her comments but have not received a reply. The French government has not responded to our request for a comment either.

What’s happened since?

In December 2019, reforms to the CFA zone were announced, dropping the requirement that countries in the zone deposit half their reserves in France.

France began the process of transferring reserves back last year, according to news reports.

The IMF said in March this year that the account where these reserves were held in France had been closed, and that the Central Bank of West African States (which controls monetary policy for eight countries including Burkina Faso) now manages the reserves.

It is free to deposit these where it chooses.

Why is the French currency zone controversial?

Critics of the CFA currency arrangement have called it a relic of colonialism, saying it has impeded economic development for the 14 African countries that are part of it.

They also argue that they have no say in deciding monetary policies agreed to by European nations in the Eurozone.

An article for the US-based Brookings Institute last year said that while countries using the CFA franc had generally seen lower inflation, the CFA franc arrangement limits their policy options, particularly in dealing with the impact of the coronavirus pandemic.

Other economists have pointed out that annual average GDP growth – the increase in the value of all goods and services produced – of CFA countries and other African economies has been fairly comparable over time.

France defends the currency system as ensuring a “stable economic framework” for the economies that are part of it, and as the currency is pegged to the Euro it says it provides better protection against economic shocks and helps control inflation.

And countries are free to leave the zone, it adds.