LONDON — The British government approved an extradition order on Friday for Julian Assange, the embattled WikiLeaks founder, confirming a court decision that he can be sent to the United States to stand trial on espionage charges, though his legal fight against the decision is not over.

While the order is a blow for Mr. Assange, whose case is seen by rights groups as a potential challenge to press freedom, he is expected to appeal the decision in a British court, and the government said he had 14 days to do so.

The Home Office, in a statement, pointed to a British court ruling that did not find “that it would be oppressive, unjust or an abuse of process to extradite Mr. Assange.” Additionally, the statement said, the courts did not find that extradition “would be incompatible with his human rights, including his right to a fair trial and to freedom of expression, and that whilst in the U.S. he will be treated appropriately, including in relation to his health.”

“This is disappointing news that should concern anyone who cares about the First Amendment and the right to publish,” said Barry J. Pollack, a lawyer for Mr. Assange in the United States. “The decision will be appealed.”

The approval of the order by Priti Patel, the home secretary, is just the latest turn in a long-running court battle and comes after a British court ordered Mr. Assange’s extradition in April.

In its statement, the Home Office said that, if Mr. Assange wishes to fight his extradition, his next legal step would be to apply to the High Court for permission to appeal against the decisions of both a district judge and Ms. Patel to order it.

In 2019, Mr. Assange was charged in the United States under the Espionage Act in connection with obtaining and publishing classified government documents about the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq on WikiLeaks in 2010. Those files were leaked by Chelsea Manning, a former military intelligence analyst, before being published by the site.

Throughout the prolonged legal battle against his extradition, Mr. Assange has remained in custody in London at Belmarsh prison, where he has been detained for nearly three years. Mr. Assange married his partner, Stella Moris, in prison this year.

“We are going to fight this, we are going to use every appeal avenue,” she said on Friday, adding, “I am going to spend every waking hour fighting for Julian until he is free, until justice is served.”

Mr. Assange was arrested in London in 2019 after spending seven years holed up in the Ecuadorean Embassy in an effort to avoid detention as he fought extradition to Sweden, where he was wanted for questioning in a rape inquiry. That case was later dropped.

Under current government guidelines, Ms. Patel is able to block extradition requests only in a small number of circumstances. Those include cases concerning people previously extradited or transferred to Britain from elsewhere, others involving people facing the death penalty, or those who might be charged with further, previously unannounced offenses after their transfers.

But if none of those issues were involved, Ms. Patel would have no reason to refuse an extradition request and would be obliged to comply, according to the Home Office.

However, Mr. Assange’s legal team will still be able to apply to appeal to Britain’s High Court on both Ms. Patel’s decision and potentially on a number of other points of concern about the U.S. request. The High Court will then decide which points Mr. Assange may appeal, if any. This process could take several months.

Once he has exhausted his options in British courts, Mr. Assange could also try to appeal to the European Court of Human Rights.

One of that court’s rulings this week grounded a flight that was scheduled to take some asylum seekers to Rwanda from Britain. Since then, some lawmakers from Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s Conservative Party have called on Britain to remove itself from the remit of the court, which is part of the Council of Europe rather than the European Union.

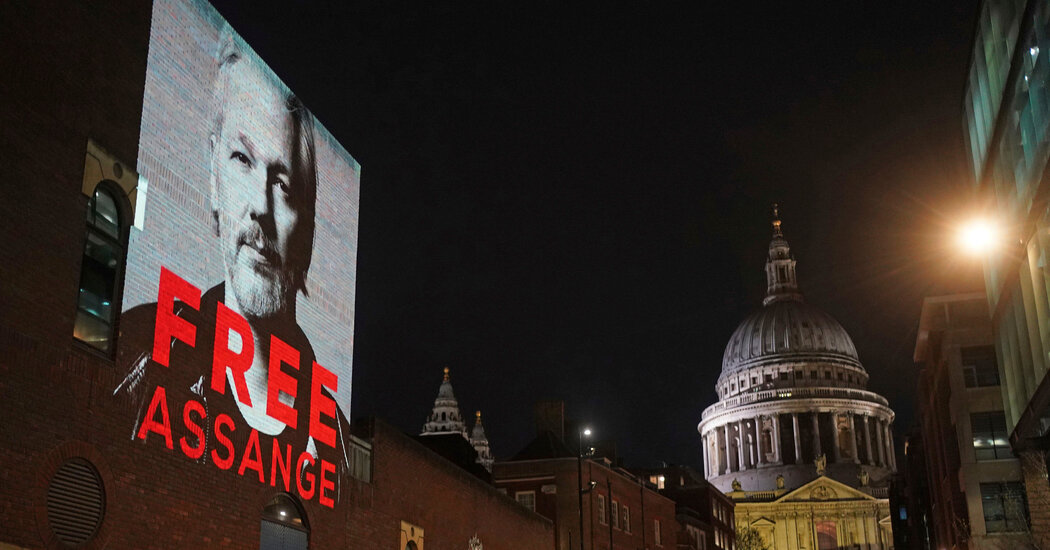

Rights groups have expressed worries that Mr. Assange’s extradition to the United States could threaten press freedom, and when the court made a decision on his case, several organizations denounced the move.

“The Home Office’s decision to extradite Julian Assange exposes its complicity in undermining press freedom just as it claims to be a world leader on freedom of expression,” Quinn McKew, the executive director of Article 19, which campaigns for freedom of expression, said in a statement.

“It also sends a worrying message to the world that journalists, activists and anyone who exposes important truths about crimes — including those committed by governments and businesses — do not deserve protection for their rights to impart information and speak freely,” the statement added.

Several opposition lawmakers expressed their concerns about the decision, as did one senior Conservative lawmaker, the former cabinet minister David Davis.

“Sadly I do not believe Mr Assange will get a fair trial,” he wrote on Twitter. “This extradition treaty needs to be rewritten to give British and American citizens identical rights, unlike now.”

Stephen Castle contributed reporting from London, and Charlie Savage from Washington.