Prosecutors in the federal trial of three former Minneapolis police officers accused in George Floyd’s killing needed to convince jurors that the officers “willfully” deprived Floyd of his civil rights.

It was a significant challenge. Jurors are likely to struggle with the concept as they deliberate, much as courts have for a century. Deliberations are expected to begin Wednesday. Here’s a look at the charges and how “willfulness” applies:

WHAT CHARGES DO THE OFFICERS FACE?

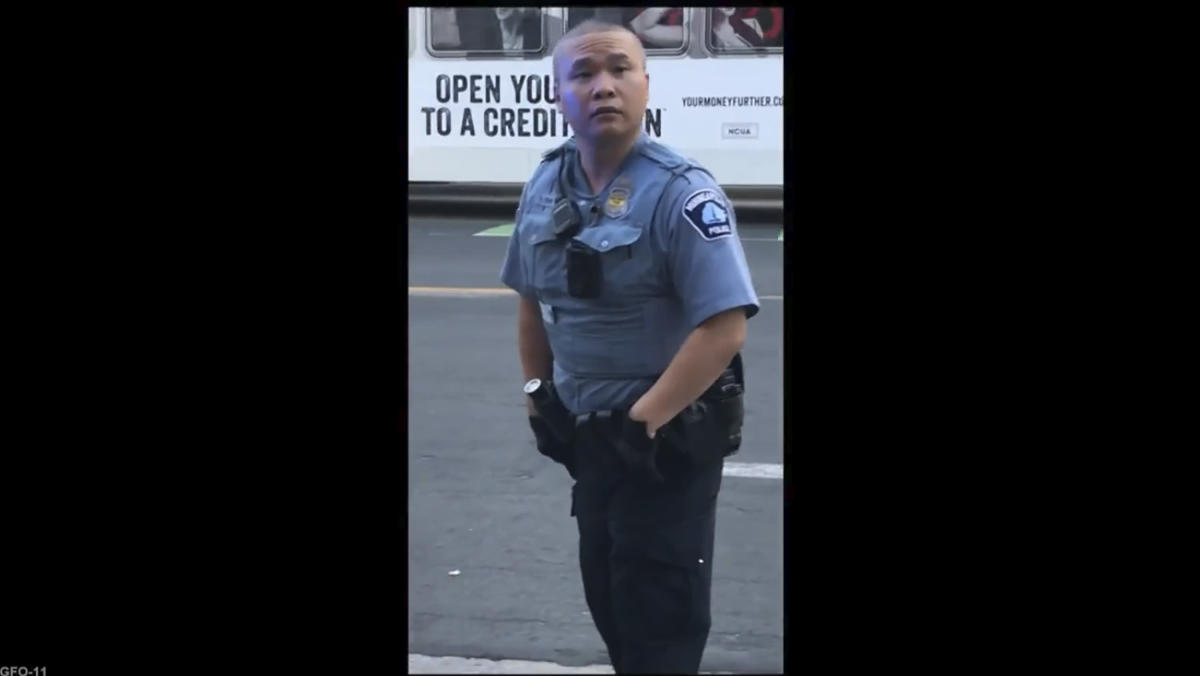

Tou Thao and J. Alexander Kueng are charged with willfully violating Floyd’s right to be free from unreasonable seizure by not intervening to stop Officer Derek Chauvin as he pinned Floyd’s neck with his knee. The indictment says they knew what Chauvin was doing and that Floyd was handcuffed, unresisting and eventually unresponsive.

Kueng, Thao and Thomas Lane are all charged with willfully depriving Floyd of his liberty without due process, specifically depriving him of the right to be free from an officer’s deliberate indifference to his medical needs. The indictment says the three men saw Floyd needed medical care and willfully failed to aid him.

Kueng knelt on Floyd’s back, Lane held his legs and Thao stopped bystanders from intervening. A prosecutor said in closing arguments Tuesday that Lane isn’t charged with failure to intervene because he asked whether Floyd should be rolled on his side.

WHAT’S THE DEFINITION OF WILLFULNESS?

Dictionaries commonly define it as purposeful adherence to an action or an obstinance to maintain a course regardless of the rules. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary includes bullheadedness and intransigence as synonyms.

In legal contexts, willfulness is intent to commit a crime plus the prior knowledge an action is illegal.

DO ALL CRIMES REQUIRE THIS ELEMENT?

No. Usually, whether someone knew that something was illegal is irrelevant. But it is germane to some charges, including those Kueng, Lane and Thao face. In such cases, ignorance is a defense.

IS WILLFULNESS A HIGH STANDARD?

Yes. It requires evidence about what officers knew at the time. The high bar is one reason prosecutors often decline to bring charges.

Then-U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara cited the law’s challenges in announcing that a white New York City police officer wouldn’t face federal civil rights charges for the 2012 fatal shooting of Ramarley Graham. The officer said he fired believing the Black teenager had a gun, although he didn’t.

“This is the highest standard of intent imposed by law,” Bharara said. “Neither accident, mistake, fear, negligence nor bad judgment is sufficient to establish a federal criminal civil rights violation.”

HOW HAVE PROSECUTORS ADDRESSED WILLFULNESS AT THIS TRIAL?

Prosecutors spent a lot of time presenting evidence of the officers’ training. They argued that the officers knew they had a duty to render medical care to a suspect in obvious need of it. Lane and Keung, while rookies, were trained about the need to turn handcuffed suspects onto their sides so that they can breathe more easily, prosecutors said.

A former head of training for the Minneapolis Police Department, Katie Blackwell, testified that officers are taught to intervene if a fellow officer uses excessive force.

Prosecutor Manda Sertich explained to jurors in her closing argument that “willfulness” doesn’t mean the government must prove the officers acted with ill will toward Floyd or intended to hurt him. She said the fact that the officers knew Floyd was in distress but did nothing after many red flags is proof of willfulness.

On the intervention charge, she said, prosecutors merely had to prove the officers knew the force Chauvin was using was unreasonable and that they had a duty to stop it — but did not.

HOW HAVE DEFENSE LAWYERS ADDRESSED WILLFULNESS?

They’ve tried to cast doubt on the quality and breadth of the officers’ training to undermine the assertion they knew their actions were unlawful.

During closing arguments, Kueng’s attorney, Tom Plunkett, hammered away at that point.

“I’m not trying to say he wasn’t trained,” Plunkett said. “I’m saying the training was inadequate to help him see, perceive and understand what was happening here.”

When questioning Blackwell, Thao attorney Robert Paule said officers “received absolutely zero training on how to use a leg” restraint. Blackwell agreed.

Lane attorney Earl Gray argued that his client was concerned for Floyd and did, per his training, ask if they should turn him on his side, but was rebuffed.

HOW DID WILLFULNESS BECOME KEY TO THE LAW?

It started with a Reconstruction-era federal law meant to protect Black people from violations of their rights. The idea of willfulness was added in 1909, but it took a landmark Supreme Court decision to highlight its importance at trials.

The case, Screws v. the U.S., involved a Georgia sheriff, Claude Screws, and two other officers who fatally beat Robert Hall after accusing him of stealing a tire. They punched the handcuffed Black man and hit him with an iron bar for 30 minutes.

The high court called the killing “shocking and revolting.” But it tossed the civil rights convictions and ordered a retrial because of vagaries in the statute and because prosecutors didn’t demonstrate that the officers specifically intended to violate Hall’s rights by killing him.

However, instead of declaring the law unconstitutional, the court directed trial courts to make willfulness a centerpiece of prosecutions. It described willfulness as acting with specific intent to deprive someone of their rights.

WHAT WAS THE RESULT?

When the lower court retried the Georgia officers under the higher standard, they were acquitted, Paul J. Watford, a U.S. appellate court judge, said in a lecture published in the Marquette Law Review in 2014. Screws went on to become a state senator.

Many viewed the new standard as a blow to civil rights protections. But Watford said that, in hindsight, the fact the justices preserved the law at least assured a U.S. government “role in combating … police brutality.”

“Had the statute instead been struck down, the power of the federal government to prosecute such abuses would have been drastically curtailed,” he said.

IS THE LAW STILL MURKY?

Reform advocates say it is.

A 2021 report from the New York-based Brennan Center for Justice called the willfulness standard “confusing and onerous.” It argued the law should list prohibited acts by police, including chokeholds on people who pose no threat, saying that would make it easier for jurors to assess guilt.

The Senate this year blocked a bill that would have made recklessness, rather than willfulness, the standard.

The bill is named the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act.

—-

This story corrects the name of the institution to the Brennan Center for Justice” instead of the Brendan Center for Justice.

___

Find AP’s full coverage of the killing of George Floyd at: https://apnews.com/hub/death-of-george-floyd