In a normal election year, races for secretary of state are sleepy affairs, and their campaigns struggle for media coverage amid the hurly-burly of more prominent Senate, governor and House contests.

This year, however, is anything but normal.

Democrats are pouring millions of dollars into races for secretary of state, buoyed by the nature of their Republican opponents and the stakes for American democracy.

According to an analysis by my colleague Alyce McFadden, Democrats in Georgia, Michigan, Minnesota and Nevada have outraised their Republican opponents as of the most recent campaign finance reports. And overall, Democratic-aligned groups working on secretary of state races in those four states have outspent Republicans by nearly $18 million in this election cycle, according to the ad analytics firm AdImpact, with more spending on the way.

The role of a secretary of state varies, but in those four states, as well as Arizona and Pennsylvania (where the governor appoints the secretary), they play a critical role in overseeing the mechanics of elections. During the height of the pandemic in 2020, for example, they often had to make judgment calls about how to ensure that voters had access to the polls when vaccines were not yet available, making elderly and immunocompromised Americans concerned about showing up in person.

The ‘Stop the Steal’ slate

Many of the Republicans running in Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Minnesota and Nevada have earned national notoriety.

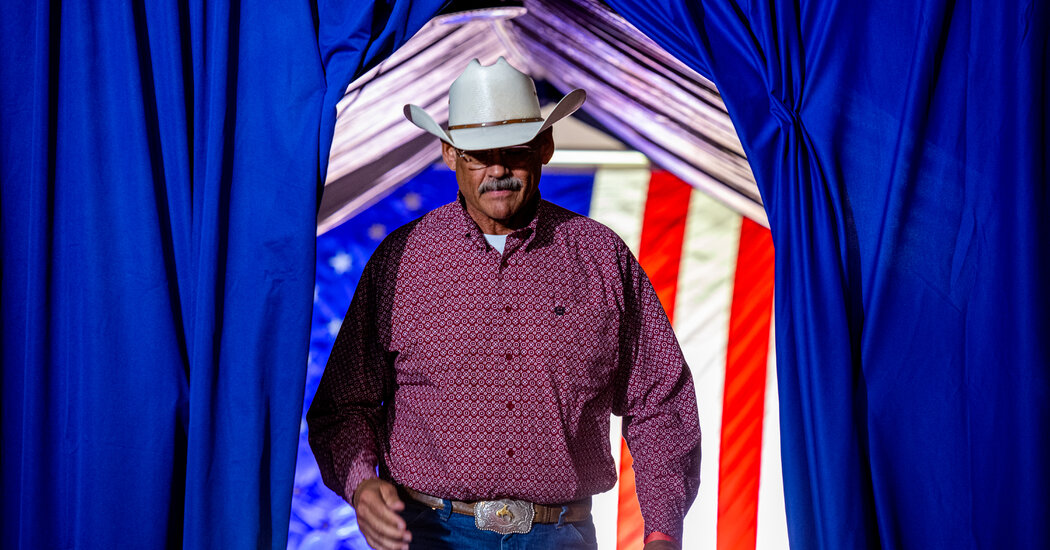

Take Mark Finchem, a cowboy-hat-and-bolo-tie-wearing Arizona lawmaker running for secretary of state. He crushed his G.O.P. rivals in the primary by whipping up fears about a stolen election in 2020.

In a recent interview with Time magazine, Finchem said it was a “fantasy” that President Biden won in 2020 — even though he was elected by more than seven million votes nationwide.

“It strains credibility,” Finchem said. “Isn’t it interesting that I can’t find anyone who will admit that they voted for Joe Biden?”

Others, such as Kristina Karamo in Michigan, have espoused fringe views on a variety of social issues. On her personal podcast, she called yoga a “satanic ritual” that was originally intended by its creators to “summon a demon.”

The State of the 2022 Midterm Elections

With the primaries over, both parties are shifting their focus to the general election on Nov. 8.

The Republican exception

Democrats are frustrated with the accolades that Brad Raffensperger, the Republican incumbent in Georgia, has received from political commentators. His refusal to overturn the 2020 presidential election results despite heavy pressure from Donald Trump, they say, was merely the minimum requirement of the job.

“It’s good when Republicans are not openly treasonous,” Jena Griswold, the secretary of state of Colorado, said in an interview.

But she accused Raffensperger of supporting what she characterized as the “worst voter-suppression package in the country” — the Republican-led law Georgia passed in 2021 overhauling voter access.

The Democratic nominee in Georgia is Bee Nguyen, a state lawmaker and policy adviser at New American Leaders, a nonprofit that encourages immigrants and refugees to run for office. Nguyen, who took the seat Stacey Abrams vacated during her first run for governor in 2017, is Vietnamese American and the first Democratic woman of Asian descent to hold a state office in Georgia.

Outside groups focused on bolstering Republicans who stood up to Trump in 2020 spent heavily on Raffensperger’s behalf in his primary against Representative Jody Hice, another Stop-the-Stealer. With the help of several million dollars in last-minute donations, along with the full backing of Brian Kemp, Georgia’s popular governor, Raffensperger defeated Hice by nearly 20 percentage points, avoiding a runoff.

A New York Times analysis of that law, Senate Bill 202, found that the state’s Republican Legislature and governor “have made a breathtaking assertion of partisan power in elections, making absentee voting harder and creating restrictions and complications in the wake of narrow losses to Democrats.”

The law alone could change turnout in Georgia, which reached record levels during two Senate elections in January 2021. Democrats say Republicans changed the law to suppress votes from people of color; in a speech in Atlanta on Jan. 11, 2022, President Biden called it “Jim Crow 2.0.”

Privately, Democrats worry, too, about complacency within their own ranks — particularly among centrists who may like the fact that Raffensperger bucked Trump’s will in 2020 but are less animated by the new voting law. Republicans have defended it as a common-sense effort to pull back what they characterized as emergency measures to accommodate voters during the pandemic. But they have struggled to explain why some measures, such as a restriction on handing out water to voters waiting in long lines, are necessary.

Griswold, a lawyer who worked on voter access for Barack Obama’s 2012 campaign, also leads the Democratic Association of Secretaries of State. She has used her national platform to reposition the organization as a bulwark of democracy against Trump and his Stop the Steal movement.

A complicated picture for Democrats

Deciding how to calibrate their message to voters about the security and fairness of the upcoming midterms has been tricky for Democrats.

That is especially true in Georgia, where newly registered voters of color powered Biden’s victory as well as those of Senators Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff. Democrats are wary of inadvertently signaling that the new voting rules could mean that those communities’ votes will be wasted this year.

Kim Rogers, the executive director of the Democratic Association of Secretaries of State, stressed in an interview that despite Republicans’ attacks on the integrity of American elections, “our system works.”

She noted that American elections are subject to “bipartisan checks and balances at every level,” with Democrats and Republicans alike enlisted to certify disputed votes and official results — while arguing that preserving these checks and balances is exactly what’s on the ballot this year.

As for the new laws in states like Georgia, she said, “voters of color have faced these suppression tactics for generations” and expressed confidence that voters would overcome those barriers just as they did in 2020.

But that system is under severe strain. Republican county officials in New Mexico, upstate New York and rural Pennsylvania have said they will refuse to certify votes from digital machines, and election officials across the country have faced death threats.

Many Democrats were highly critical of the Biden administration’s strategy for pushing an overhaul of voting rights through Congress. It failed in January while facing unified Republican opposition and skepticism from centrist Democrats, led by Senator Joe Manchin III of West Virginia.

Vice President Kamala Harris, the administration’s point person for voting rights, has faced repeated questions about what she has done to find workarounds in lieu of federal legislation, beyond making the occasional speech.

Democrats pushed to appropriate federal funds to protect election workers in legislation to overhaul the Electoral Count Act, but Republicans have resisted. On Wednesday, the House passed its version of an overhaul bill, but the Senate will need to pass its own, different version, as my colleague Carl Hulse reported.

His article contained a quote from Senator Susan Collins of Maine, who is the leading Republican author on the Senate side but has provoked concerns among Democratic colleagues, including Tim Kaine, with whom I spoke in March. They say that she is merely maneuvering to run out the clock at the bidding of Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, the minority leader.

“We can work together to try to bridge the considerable differences,” Collins told Hulse. “But it would have been better if we had been consulted prior to the House sponsors’ deciding to drop their bill.”

What to read

Thank you for reading On Politics, and for being a subscriber to The New York Times. — Blake

Read past editions of the newsletter here.

If you’re enjoying what you’re reading, please consider recommending it to others. They can sign up here. Browse all of our subscriber-only newsletters here.

Have feedback? Ideas for coverage? We’d love to hear from you. Email us at onpolitics@nytimes.com.