WASHINGTON — In the spring of 1985, a 35-year-old lawyer in the Justice Department, Samuel A. Alito Jr., cautioned the Reagan administration against mounting a frontal assault on Roe v. Wade, the landmark ruling that declared a constitutional right to abortion. The Supreme Court was not ready to overturn it, he said, so urging it to do so could backfire.

In a memo offering advice on two pending cases that challenged state laws regulating abortion, Mr. Alito advocated focusing on a more incremental argument: The court should uphold the regulations as reasonable. That strategy would “advance the goals of bringing about the eventual overruling of Roe v. Wade and, in the meantime, of mitigating its effects.”

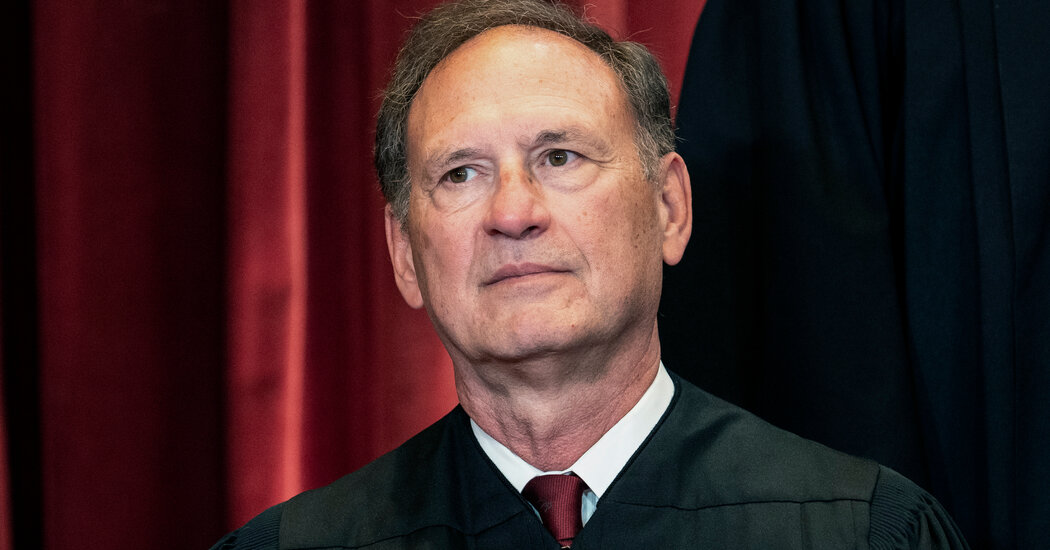

More than three decades later, Justice Alito has fulfilled that vision, cementing his place in history as the author of a consequential ruling overturning Roe, along with a 1992 precedent that reaffirmed that decision, Planned Parenthood v. Casey. The reversal means tens of millions of women in conservative-controlled states are losing access to abortion.

The move has cast a spotlight on a man who has otherwise been a lower-profile member of the court’s conservative bloc since his appointment by President George W. Bush more than a decade ago. It has also drawn attention to glimpses of how he slowly and patiently sought to chip away at abortion rights throughout his career before demolishing them in the majority opinion on Friday.

“Roe was egregiously wrong from the start,” Justice Alito wrote. “Its reasoning was exceptionally weak, and the decision has had damaging consequences. And far from bringing about a national settlement of the abortion issue, Roe and Casey have enflamed debate and deepened division.”

Born in 1950 to a Catholic, Italian American family, Justice Alito grew up in New Jersey. Two conservative standard bearers inspired his interest in political conservatism, he later noted, pointing to the writings of William F. Buckley Jr. and Barry M. Goldwater’s 1964 presidential campaign.

Mr. Alito became interested in constitutional law during college largely because he disagreed with the Supreme Court at the time on criminal procedure, the establishment clause and reapportionment, he has written. The court in the 1960s issued rulings on those topics that conservatives disliked, including protecting the rights of suspects in police custody, limiting prayer in public schools and requiring electoral districts to have roughly equal populations.

He was a first-year law student at Yale Law School in 1973 when the Supreme Court handed down Roe. While progressives hail the case as a momentous outcome for women’s equality and reproductive freedom, its constitutional reasoning drew sharp criticism across ideological lines — a pattern Justice Alito stressed with apparent relish in his opinion.

Even “abortion supporters have found it hard to defend Roe’s reasoning,” he wrote. “One prominent constitutional scholar wrote that he ‘would vote for a statute very much like the one the Court end[ed] up drafting’ if he were ‘a legislator,’ but his assessment of Roe was memorable and brutal: Roe was ‘not constitutional law’ at all and gave ‘almost no sense of an obligation to try to be.’”

Justice Alito was quoting a 1973 Yale Law Journal article on the decision by John Hart Ely, who taught at the school at the time.

After graduation, he went on to clerk for a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit, eventually landing a job as a federal prosecutor in New Jersey. Once Ronald Reagan won the 1980 presidential election, he followed the path of many young conservative lawyers, joining the administration and working in the solicitor general’s office.

Among political appointees, overturning Roe was a paramount long-term goal for the Reagan administration. It fused the desires of elite conservative legal thinkers with those of the religious right. But in 1983, over the Reagan administration’s objections, the Supreme Court instead reaffirmed Roe.

In the spring of 1985, the two cases arose challenging state laws that regulated abortion, including by requiring doctors to tell women seeking the procedure detailed information about its risks and “unforeseeable detrimental effects,” the development of fetuses, and the availability of adoption services or paternal child support.

In a memo on the cases, Mr. Alito displayed not only tactical acumen but personal passion, taking umbrage with a judge’s objection that forcing women to listen to details about fetal development before their abortions would cause “emotional distress, anxiety, guilt and in some cases increased physical pain.”

Good, he wrote: Such results “are part of the responsibility of moral choice.”

Later that year, Mr. Alito applied for another position in the Justice Department, proudly citing his role in devising a strategy for those cases. “I personally believe very strongly,” he wrote in an application, that “the Constitution does not protect a right to an abortion.”

Years later, when those documents were disclosed during his Supreme Court confirmation, he assured senators that while that statement reflected his views in 1985, he would approach abortion cases with an open mind as a justice, with due respect for precedent and with no ideological agenda.

“When someone becomes a judge,” he said, “you really have to put aside the things that you did as a lawyer at prior points in your legal career and think about legal issues the way a judge thinks about legal issues.”

Before Justice Alito joined the Supreme Court, he served on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit. As an appellate judge, he lacked the power to overrule Roe. But he sometimes seemed to look for ways to whittle away at it in cases touching on abortion, dovetailing with his formative advice during the Reagan administration.

The most notable was Planned Parenthood v. Casey, the case in which the Supreme Court reaffirmed the central holding of Roe but permitted states to impose more restrictions in the first trimester. It involved a challenge to a Pennsylvania law imposing requirements before an abortion, including a waiting period, parental consent for minors and notifying a woman’s husband.

Before it reached the high court, the case came before a Third Circuit panel that included Judge Alito. The other two judges on the panel voted to uphold most of the law, but they struck down the provision mandating spousal notification. Judge Alito wrote separately to dissent from that part, saying it should stand, too.

That requirement, he argued, did not impose an “undue burden” on abortion access, so it was enough that “Pennsylvania has a legitimate interest in furthering the husband’s interest in the fate of the fetus.” Nor, he wrote, should judges second-guess the state legislature’s decisions on the adequacy of several exceptions it included for certain cases.

And in 2016 and 2020, he was among the dissenters when the court narrowly voted to strike down nearly identical Texas and Louisiana laws that strictly regulated abortion clinics in ways that forced many to close.

The majority said in 2016 that the Texas law imposed an undue burden on access to abortion and in 2020 that a challenge to the Louisiana law was controlled by the earlier precedent. Both times, Justice Alito wrote lengthy opinions saying the challenges to those laws should have been rejected for procedural reasons.

But in 2016 and 2020, just as in 1985, a new frontal attack on abortion rights would have failed. With Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg still on the bench, there were not five votes to overturn Roe. This year, there was no longer need for a restrained, slower-burning approach.

Over the objections of Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. — who agreed that a Mississippi law banning abortions after 15 weeks should be upheld, but said that the majority’s “dramatic and consequential ruling is unnecessary to decide the case before us” and violated the principle of judicial restraint — the long-envisioned time for a direct assault on Roe had come.

“Abortion presents a profound moral question,” Justice Alito wrote. “The Constitution does not prohibit the citizens of each state from regulating or prohibiting abortion. Roe and Casey arrogated that authority. We now overrule those decisions and return that authority to the people and their elected representatives.”