Just days before Bruce Willis was scheduled to turn up on the set of one of his latest action films, the director of the project sent out an urgent request: Make the movie star’s part smaller.

“It looks like we need to knock down Bruce’s page count by about 5 pages,” Mike Burns, the director of “Out of Death,” wrote in a June 2020 email to the film’s screenwriter. “We also need to abbreviate his dialogue a bit so that there are no monologues, etc.”

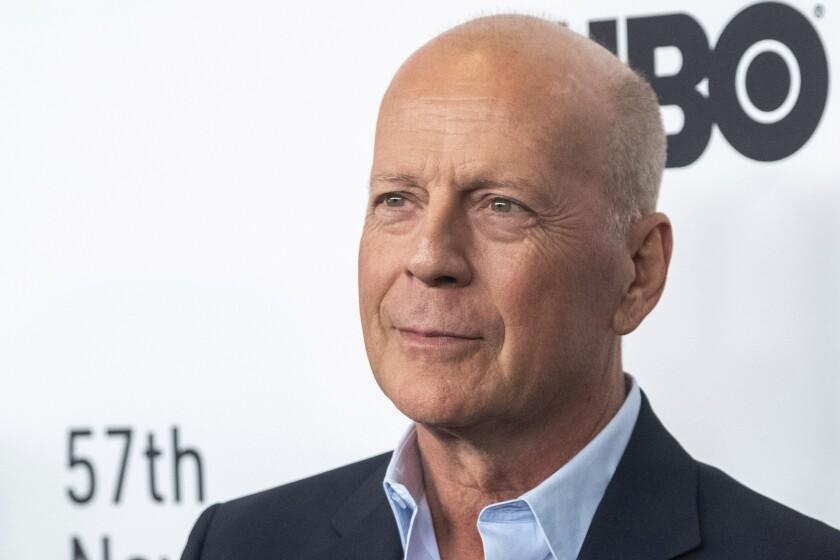

Burns did not outline one of the reasons why Willis’ lines needed to be kept “short and sweet.” But on Wednesday, the public learned what he and many other filmmakers have privately been concerned about for years: The 67-year-old’s family said he will retire from acting because he has aphasia. The cognitive disorder affects a person’s ability to communicate and often develops in individuals who have suffered strokes.

“As a result of this and with much consideration Bruce is stepping away from the career that has meant so much to him,” the actor’s daughter Rumer Willis wrote in an Instagram post also signed by her siblings, the actor’s wife, Emma, and his former wife, Demi Moore.

According to those who have worked with the elder Willis on his recent films, the actor has been exhibiting signs of decline in recent years. In interviews with The Times this month, nearly two dozen people who were on set with the actor expressed concern about Willis’ well-being.

These individuals questioned whether the actor was fully aware of his surroundings on set, where he was often paid $2 million for two days of work, according to documents viewed by The Times. Filmmakers described heart-wrenching scenes as the beloved “Pulp Fiction” star grappled with his loss of mental acuity and an inability to remember his dialogue. An actor who traveled with Willis would feed the star his lines through an earpiece, known in the industry as an “earwig,” according to several sources. Most action scenes, particularly those that involved choreographed gunfire, were filmed using a body double as a substitute for Willis.

In one alleged incident two years ago on a Cincinnati set of the movie “Hard Kill,” Willis unexpectedly fired a gun loaded with a blank on the wrong cue, according to two people familiar with the incident who were not authorized to comment. No one was injured. The film’s producer disputed that the incident occurred, but the alleged discharge left actors and crew members shaken.

Burns was one of a handful of people who knew Willis was struggling with his memory, but he said he was unaware of the severity of the actor’s condition until June 2020, when he was directing his first film, “Out of Death.” It was among 22 films Willis did in four years.

“After the first day of working with Bruce, I could see it firsthand and I realized that there was a bigger issue at stake here and why I had been asked to shorten his lines,” Burns said. On that film, Burns was tasked with compressing all of Willis’ scenes — about 25 pages of dialogue — into one day of filming, which he said was exceedingly difficult. At the end of the day, Burns felt conflicted.

Last fall, Burns was offered the chance to direct another Willis film, “Wrong Place,” but he was worried about the actor’s health.

Burns said he called one of Willis’ associates and asked him: “How’s Bruce?” Burns said he was told that Willis was “a whole different person … way better than last year.” “I took him at his word,” Burns said.

But when they started filming the movie last October, “I didn’t think he was better; I thought he was worse,” Burns said. “After we finished, I said: ‘I’m done. I’m not going to do any other Bruce Willis movies.’ I am relieved that he is taking time off.”

A representative for Willis declined to comment beyond the family statement.

Willis’ longtime management team — including a powerhouse group of agents at the Creative Artists Agency — made sure that his film shoots were limited to two days. The actor’s contracts stipulated that he was not to work more than eight hours a day, but he often stayed for only four, according to production sources.

Meanwhile, fans online began questioning why Willis was cranking out so many low-budget films, most of which were panned by critics. The group behind the Razzie Awards, which each year compiles a list of the industry’s worst films, in February created an entire category for Willis’ films.

Some film directors told The Times that they were startled by Willis’ condition in the last year.

Jesse V. Johnson, who directed the low-budget film “White Elephant,” first worked with Willis decades ago when he was a stuntman. But when the filmmaker and the actor met briefly before shooting began in Georgia last April, “it was clear that he was not the Bruce I remembered,” Johnson said.

Concerned about Willis’ mental state, he said he approached the actor’s team — which is led by his assistant-turned-handler Stephen J. Eads — and bluntly asked about the actor’s condition.

“They stated that he was happy to be there, but that it would be best if we could finish shooting him by lunch and let him go early,” Johnson recalled of the conversation. Filmmakers proceeded to quickly film the actor’s parts, even as Willis questioned where he was: “I know why you’re here, and I know why you’re here, but why am I here?” two crew members said he asked aloud.

“It was less of an annoyance and more like: ‘How do we not make Bruce look bad?'” one of the crew members said. “Someone would give him a line and he didn’t understand what it meant. He was just being puppeted.”

Johnson, the director, said he subsequently was offered the opportunity to film two additional movies with Willis, so he discussed the situation with his creative team.

“After our experience on ‘White Elephant,’ it was decided as a team that we would not do another,” Johnson said. “We are all Bruce Willis fans, and the arrangement felt wrong and ultimately a rather sad end to an incredible career, one that none of us felt comfortable with.”

Though he has appeared in more than 70 films since he began acting in the 1970s, Willis is still best recognized for playing detective John McClane in the “Die Hard” franchise. The role — which he reprised in five movies — helped to cement his status as one of Hollywood’s leading action heroes, landing him parts in films such as “Pulp Fiction” and “The Fifth Element.” Although he was often recognized more as a box office draw than a critical darling, he received a Golden Globe for his role opposite Cybill Shepherd in the 1980s television series “Moonlighting” and has worked with directors such as Wes Anderson and Terry Gilliam.

Even as Willis’ health declined, he remained in high demand.

His involvement in films — even if for a fleeting few minutes — helped low-budget independent filmmakers sell their films internationally. Having Willis’ face on a movie poster or a lineup of streaming service thumbnails helped draw viewers to his films. In recent years, Willis worked primarily for two film production companies: Los Angeles-based Emmett/Furla Oasis and 308 Entertainment Inc., a Vancouver company backed by actor and producer Corey Large, according to IMDb.com.

In January 2020, actress Lala Kent, a star of Bravo’s “Vanderpump Rules” reality show, was cast as the action hero’s daughter in “Hard Kill.” In one scene, Kent said, Willis’ character was scripted to step in and protect her from villains.

“I’m supposed to think my life is about to end, and then my dad steps in to save the day,” Kent said, describing how her back was to Willis in the scene. Willis was meant to deliver a line that served as Kent’s cue to duck before he fired the weapon at a bad guy. Instead, he shot the gun before delivering the line — and the actress was unable to duck.

“Because my back was to him, I wasn’t aware of what was happening behind me. But the first time, it was like, ‘No big deal, let’s reset,’” she said.

Kent said she asked director Matt Eskandari to remind Willis to say his line before firing the gun.

But on the second take, the same thing happened, Kent said. Eskandari did not respond to calls seeking comment, but a second crew member said he remembered Kent being shaken that day. A third crew member, who also was not authorized to comment publicly, said he recalled a situation in which Willis “did fire the gun on the wrong line.”

But the crew member added: “We always made sure no one was in the line of fire when he was handling guns.”

Randall Emmett, co-founder of Emmett/Furla Oasis, who has worked on 20 Willis movies, declined to comment on Willis’ condition, citing medical privacy laws. But Emmett, who is Kent’s former fiance, disputed that Willis fired a gun prematurely. The film’s armorer denied that the incident occurred.

In a statement, Emmett said: “I fully support Bruce and his family during this challenging time and admire him for his courage in battling this difficult medical condition. Bruce will always be a part of our family.”

Willis had a large entourage that accompanied him on set, and its members were protective of the actor, according to several filmmakers.

Eads, who began working with Willis as his assistant in the 1990s, served as his on-set handler.

“The guy guided Bruce everywhere,” one crew member on 2020’s “Hard Kill” said of Eads. “He carted him around and kept an eye on him.”

For his work, he is credited as a producer on Willis’ films. In December 2018, Eads entered into a three-picture deal with the now-defunct MoviePass Films for which Eads received $200,000 per picture, according to a contract reviewed by the The Times.

“We look forward to continuing our long relationship with you on these and other films to come,” read the deal sent to Eads by Emmett, the chief executive of the production company. Just over a year later, Eads entered into a new certificate of engagement for $200,000 with Georgia Film Fund 70 LLC — another of Emmett’s companies — to work on “Hard Kill,” then called “Open Source.” Eads did not respond to requests for comment.

In addition, actor Adam Huel Potter was guaranteed bit roles in Willis films and served as Willis’ prompter, providing the actor his lines through the ear piece. Potter was paid $4,150 per week, according to Willis’ contract on “Open Source.” He was offered “an on-screen speaking role” and provided with accommodations in Willis’ hotel, according to the document. Potter did not respond to inquiries from The Times about this arrangement.

One of Willis’ final larger-scale films, “Paradise City,” was filmed on the Hawaiian island of Maui last May, after the pandemic delayed production for a year. Chuck Russell, the film’s director, and a second crew member said Willis was thrilled to be reunited with a fellow “Pulp Fiction” star in Hawaii. (The film is scheduled for release this summer.)

“He was excited to work with John Travolta, and you could see the old Bruce Willis charm was still there,” Russell said. “He really brought his A game, and we made sure that he and John had a great experience filming together.”

But the filmmakers who spoke with The Times said they were alarmed by his condition.

“He just looked so lost, and he would say, ‘I’ll do my best.’ He always tried his best,” Terri Martin, the production supervisor on “White Elephant,” said Wednesday. “He is one of the all-time greats, and I have the utmost admiration and respect for his body of work, but it was time for him to retire.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.