One candidate is Gustavo Petro, a former rebel and longtime senator who is making a bid to become Colombia’s first-ever leftist president, calling for a transformation of the economic system.

The other is Rodolfo Hernández, a construction magnate who has become the country’s most disruptive political phenomenon in a generation, galvanizing voters largely through his outsize social media presence with promises of “total austerity” and a scorched-earth approach to corruption.

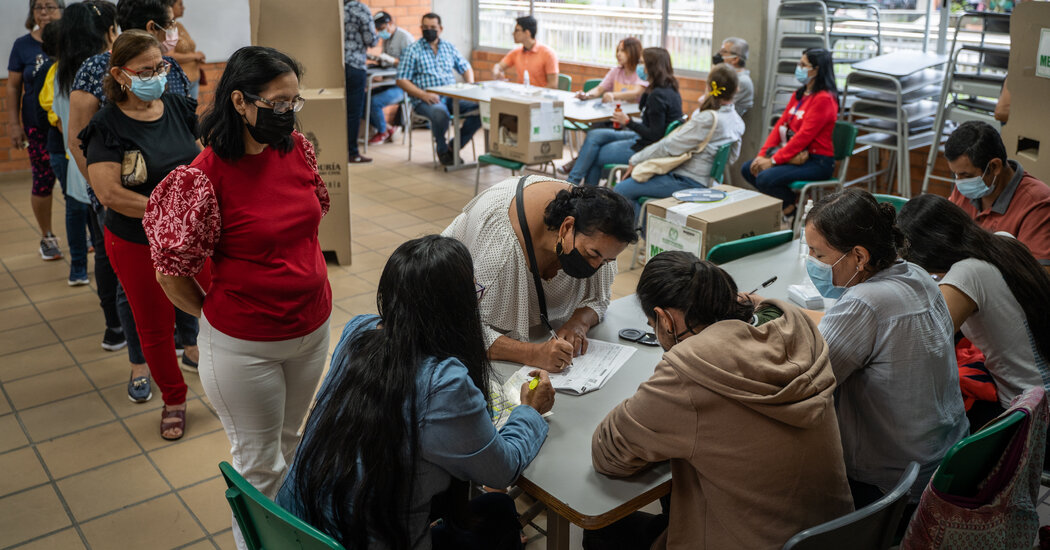

At stake in Sunday’s presidential election is the fate of the third largest nation in Latin America, where poverty and inequality have risen during the pandemic and polls show increasing distrust in nearly all major institutions. Anti-government protests last year sent hundreds of thousands of people into the streets in what became known as the “national strike”, whose shadow hangs over Sunday’s vote.

“The entire country is begging for change,” said Fernando Posada, a Colombian political scientist, “and that is absolutely clear.”

The candidates enter the election virtually tied in the polls, and the result could be so close that it takes days to determine a winner.

Whoever ultimately scores a victory will be charged with tackling the country’s most pressing issues and their global repercussions: lack of opportunity and rising violence, which have prompted record numbers of Colombians to migrate to the United States in recent months; high levels of deforestation in the Colombian Amazon, a critical buffer against climate change; and growing threats to democracy, part of a trend around the region.

Both candidates inspire anger and hope in voters, and the election has divided families, dominated the national conversation and brought a glossary’s worth of internet memes that form a snapshot of the national mood: Mr. Hernández calling his doubters “crazy” on TikTok; Mr. Petro promoting a jingle encouraging a twist on the illicit practice of vote buying.

“You fool them first,” goes the chorus, referring to the country’s political establishment, “take their cash — and vote for Petro!”

Both candidates say they are running against a conservative elite that has controlled the country for generations.

Among the factors that most distinguishes them is what they see as the root of Colombia’s problems.

Mr. Petro believes the economic system is broken, overly reliant on oil exports and a flourishing and illegal cocaine business that he said had made the rich richer and poor poorer. He is calling for a halt to all new oil exploration, a shift to developing other industries, and an expansion of social programs, while imposing higher taxes on the rich.

“What we have today is the result of what I call ‘the depletion of the model,’” Mr. Petro said in an interview, referring to the current economic system. “The end result is a brutal poverty.”

His ambitious economic plan has, however, raised concerns. One former finance minister called his energy plan “economic suicide.”

Mr. Hernández does not want to overhaul the economic framework, but says it is inefficient because it is riddled with corruption and frivolous spending. He has called for the combining of ministries, eliminating some embassies and firing inefficient government employees, while using savings to help the poor.

“The feeling they have,” he said of his supporters, “is that I have the ability to confront the political cabal, to remove them from power to reclaim the rights of the poorest.”

His critics say he is proposing a brutal form of capitalism that will hurt the nation.

Mr. Petro is accused by former allies of an arrogance that leads him to ignore advisers and struggle to build teams. Mr. Hernández is accused of being vulgar and domineering, and has been indicted on corruption charges, with a trial set for July 21. He says he is innocent.

No matter the result, the country will have a Black woman as vice president for the first time: Francia Márquez, an environmental activist on Mr. Petro’s ticket, or Marelen Castillo, a former university administrator running on Mr. Hernández’s ticket.

In May, during the first round of voting, Yojaira Pérez, 53, in the northern department of Sucre, called her vote for Mr. Petro a kind of retribution, reflecting the mood of an electorate that has helped elevate the candidacies of the two men competing on Sunday.

“We have to punish the same old politicians who have been dominant in Colombia,” she said, “who have wanted to govern and manage Colombia as if it were a puppet, as if we were their puppets.”