“Ugh, why can’t I just be chill? Just a modicum of chill. That would be great.” In his production office on the Sony lot where he is putting the final touches on the coming season of his HBO show Barry, Bill Hader recalls — with no small amount of angst — meeting some of his filmmaker idols as a castmember on Saturday Night Live. He would often corner the guests with breathless, fannish questions about their work. “How do you do this? How do you do that?” When Paul Thomas Anderson, who is partnered with former SNL castmember Maya Rudolph, came to set, “He was super nice but a bit like, ‘Easy, man, relax,’ ” Hader says. “I don’t know what I said, but I just felt the vibe from him was, ‘Please get out of my dressing room.’ It could just be in my head, but I just felt like he could smell, ‘Oh, you’re a film nerd. OK. Thanks, man.’ ” Hader says he’s had similar encounters with Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese.

Now, after years of admiring such filmmakers to the point of mortification, Hader, 43, is becoming something more akin to a peer, taking on greater creative responsibility for one of TV’s most cinematic shows. Hader co-created Barry with Alec Berg, writes and directs most of the episodes, and is finally fulfilling the goal that brought him to Hollywood in 1999, before he got sidetracked by a detour into one of the most coveted jobs in comedy: that of auteur.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

In Barry, which returns to HBO for its third season April 24, Hader plays a reluctant hitman who wants to be an actor. Barry is just really great at killing. This is not so different, Berg points out, from Hader, who became a star on SNL in his 20s almost in spite of himself, fought crippling anxiety on the live broadcasts, and really just wanted to write and direct.

“He didn’t spend six years doing ImprovOlympic or whatever it was,” Berg says. “He fell ass-backward into it. And he’s just so unbelievably good at [comedy and acting] that it just willed itself into being, and he couldn’t stop it. We both thought the idea of somebody who was incredibly naturally gifted at something that they didn’t love doing was an interesting internal struggle, the struggle of like, ‘Oh, well he should be a killer because he is great at it, but it’s eating him up.’”

On the third season of Barry, Hader directed five of the eight episodes, and on season four, which is already outlined and being written, he plans to direct every one. It’s an assumption of responsibility he’s been gunning for since he and Berg first sold HBO the pilot for Barry in 2016. At that meeting, Hader, who had directed a few episodes of Curb Your Enthusiasm, volunteered to direct the pilot, and the network said yes in the room. But as soon as the meeting was over, then-HBO president of programming Michael Lombardo called Berg, a TV veteran and executive producer on Seinfeld, Curb and Silicon Valley, in his car. “[Lombardo] goes, ‘Look, I know in the room you had to say that Bill could direct it because Bill is sitting there, but there’s no one else on the phone. Can he do this?’” Berg recalls. “And I said, ‘100 percent, absolutely, there’s no doubt he can do it. And he should.’”

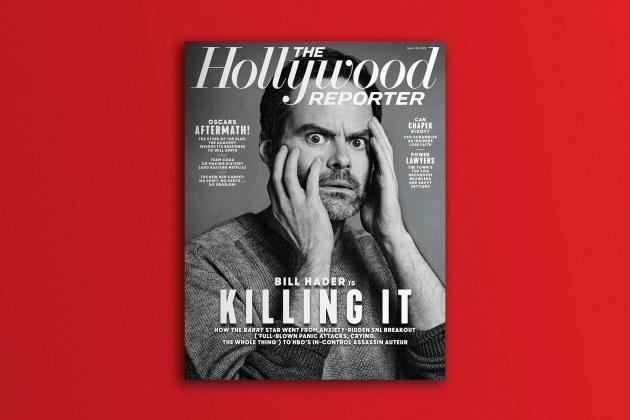

Photographed by David Needleman

Hader had communicated his ideas about visual references and tone so clearly as he and Berg were honing the idea for Barry that Berg felt confident. Hader would go on to be nominated for an Emmy for directing the pilot, and another for directing an episode in season two, a surrealist one-off that subjects Barry to extended fight sequences, first with a martial arts master and then with that man’s preteen daughter, described as a “feral mongoose.” In total, the show was nominated for 30 Primetime Emmys during its first two seasons, and both Hader and co-star Henry Winkler, who plays Barry’s acting coach, won for their performances.

When Hader pivots between acting in a scene and directing it, Winkler says, “I don’t know how it’s done, but you don’t see the seam. He goes, ‘Let’s do it again. You know what? Try this.’ And then, boom. He’s in the scene with you.” Hader has gained more confidence since his early days directing on the show, Winkler says, and lost one distracting habit. “He used to mouth your words,” Winkler says. “He knew everybody’s lines because he wrote them, he and his wonderful staff. And you would see him saying your line with you and you would have to say, ‘Bill, Bill, you’re mouthing the words again.’”

The appeal of Barry was never the acting, Hader says. “It was about figuring out what’s the story, and getting into the tone and the feel of it. And then being like, ‘Oh, I guess I’ll play Barry.’”

But as an acting role, Barry has been an evolution for Hader — his second. At some point, perhaps when he played Amy Schumer’s boyfriend in Trainwreck or Kristen Wiig’s sensitive, depressed brother in the indie drama Skeleton Twins, Hader’s public image evolved from the weirdo in the ascot playing Vincent Price on SNL to that of a thinking woman’s heartthrob. But on Barry, he plays a former Marine prone to violence and capable of towering rage. It’s a role that relies on physicality and athleticism. When he first got the part, “I remember HBO being like, ‘You need to start working out,’” Hader says. “And I’m like, ‘I actually do work out. I work out three days a week, sometimes more. I work out a lot.’ I never get, ‘Wow, you look great.’ It’s always like, ‘Huh.’ Once I was like, ‘I just don’t want to be too ripped.’ [My trainer] was like, ‘I don’t think you have to worry about that.’”

Lionsgate/Courtesy Everett Collection

Season three of Barry was fully written before the pandemic and was two weeks from the start of production when it shut down. While waiting for it to be safe to start shooting again, Hader and Berg opened a virtual writers room to write season four, and Hader realized he wanted to go back into the scripts for season three. “We were trying to get more to the reality of things,” Hader says. “Are we getting to the honesty of this, the brutal honesty of it? Are we going too far? Is this too silly? Is this too disturbing?”

The new season sees Barry descending to new depths. While watching one episode, one of the show’s writers had a panic attack. “Barry’s back is against the wall and he’s freaking out and he has this in him,” Hader says. “There’s only a matter of time before it starts going out on the people he loves. In the writers room, people go, ‘Well, that’s going to be really upsetting.’ And it’s like, ‘But yeah, to not do it, it feels like we’re purposely avoiding it. And you don’t want to go, ‘Well, he’s only mean to these people.’ It’s like, ‘No, he’s mean to everybody.’”

If audiences didn’t lose their fondness for Barry when he was fighting a preteen girl in season two, season three will further test that affection, which relies on a mixture of the character’s earnest determination to overcome his past and on Hader’s own Midwestern likability. “I don’t know if he will hold the audience’s loyalty this season,” Hader says. “It’s OK. I remember watching Goodfellas growing up and going like, ‘Wow, look at his life. This is great.’ And then they shoot Spider [Michael Imperioli’s character], and you just knew that this was real.”

Hader is willing to risk audiences turning against the increasingly dark killer he plays in Barry: “With movies where they were trying to make sure that you liked the main character, I would always feel a little cheated. As you get older, you just see that life is more like Goodfellas.”

Courtesy of HBO

***

Hader is the kind of guy whose brain whirs with worries, and he has talked openly about the anxiety that led to panic attacks when he was in the cast of SNL from 2005 to 2013. Of all the characters he’s played, perhaps the one he most closely resembles is Fear from Pixar’s Inside Out, the purple, quavering animated representation of that emotion who was prone to making lists of possible calamities. “Anxiety is always fighting those voices in your head saying, ‘Here’s all the bad things that are going to happen,’” Hader says. “Weirdly, I have a harder time with day-to-day stuff, as opposed to running a TV show.”

As it did for many, the pandemic exacerbated Hader’s anxiety, worsening the migraines he has suffered from for years. He has an autoimmune condition, takes immune-suppressing medication and almost never left his house from March 2020 until he was fully vaccinated in the spring of 2021. Hader wears an N95 mask to work on the Sony lot, where masking is optional, and toggles between worrying about getting COVID-19 and worrying about whether the stress from worrying is triggering his autoimmune condition. While making the third season of Barry under pandemic protocols, Hader layered on another concern: “I thought, ‘If I get COVID, it’s going to cost a shit ton of money,’” he says. “And so I was very, very strict. I put myself under a lot of pressure. I just don’t like that that’s taking up space in my brain when I have all this other shit I’m trying to do.” He recently took one of his daughters to an outdoor birthday party. “No one was wearing masks,” he says. “So I took my mask off and was like, ‘All right, right. I’m doing it.’”

Hader says he has been “spazzy” since he was a kid growing up the oldest of three in Tulsa, Oklahoma, his mother a dance teacher, his father the owner of an air cargo company. As a worried child, Hader was often told he was being overdramatic. “And it’s like, ‘Yeah, maybe I am,’” he says. “But it is very real in your head. Teachers were like, ‘Oh God, you’re really sensitive.’ I also had a peanut allergy, and they didn’t believe that either in the ’80s.”

One of Hader’s coping strategies is to find some sugar. Once while working at SNL on a Friday night at 2 a.m., he ate an Entenmann’s coffeecake with his bare hands in the aisle of the Gristedes grocer in 30 Rock. “And then the shame of bringing the empty box up to the cashier and him being like, ‘Dude,’” Hader says. “And I was like, ‘Yeah, man.’ I’ve walked to Vons at midnight with a spoon in my pocket because I know I’m going to buy ice cream and I’m going to eat it on the way back. The minute it’s mine, I’m eating this shit and I’ll probably finish it before I get back home. And it just makes me feel like a piece of shit. But, yeah, that’s my stress thing.”

In 1999, Hader dropped out of Scottsdale Community College and moved to L.A. He found work through ads in the back pages of The Hollywood Reporter, and among his early jobs in the business was as a production assistant on the 2002 Spider-Man, which was shot on the Sony lot where he runs Barry 20 years later. In the early 2000s, while underemployed in the entertainment industry, Hader was also appearing in backyard comedy shows in Van Nuys with his friend Matt Offerman, attracted by the chance to have some kind of creative outlet but not looking for a performance career. One night Offerman’s brother, Nick, invited his wife, Megan Mullally, to a show, and she was so impressed by Hader, she recommended him to SNL creator Lorne Michaels, launching Hader on a new and unplanned career trajectory, at which he was wildly successful. He was also miserable.

“The live aspect of SNL — I’m just not built for it,” he says. “Before shows, I would go into a bathroom that was way down this hall, go into a stall and have a full-blown panic attack, crying, the whole thing. And then I go and get in a giant banana costume. This voice would come on in my head of like, ‘You fucking asshole, do you know how many people would kill for this? Dude, get your shit together, come on.’”

Movies and TV have always been a source of solace, and friends describe Hader as having an encyclopedic awareness of film references acquired while parked in front of his TV/VCR combo as a child. “His knowledge of film and comedy is insane, voluminous and complete,” says John Mulaney, who wrote with Hader on SNL, co-creating his most famous character, New York nightlife guide Stefon. “Bill has a strong sense of what he likes and dislikes, and that comes in large part from seeing everything.”

Hader’s classic film references occasionally surfaced on SNL in ways that felt surprising for a show that relies on topicality, as when he played Vincent Price hosting a holiday special. “When Bill first did Vincent Price, Lorne walked up to him right before it went live on TV and said, ‘I like this, but why now?’” Mulaney says. “The ‘Why now?’ comment kind of hung in the air with us a lot. Why now write a piece where Bill is Burt Lancaster? He’s so funny, and he understands that the specific is universal. I don’t think many people in the audience knew Vincent Price, but they knew that they were watching a guy trying to be upbeat and hosting a holiday special who is extremely put upon by absolutely ridiculous and rude guests.”

NBC/Photofest

Despite his fears about live performance on SNL, Hader had a fearless loyalty to his own taste. “When Bill showed up to SNL, his comedy was very specific, which delights writers but is sometimes harder for audiences to grasp,” says Seth Meyers, who was co-head writer at SNL during Hader’s time there. “What was amazing over his tenure is how he broadened his appeal without ever sacrificing his taste. He taught people to love what he did rather than try to do what they liked.”

Hader’s specificity has shown up in his post-SNL choices as well. Among his first projects was Documentary Now!, the niche IFC mockumentary series he co-created with Meyers, Fred Armisen and Rhys Thomas in 2015 (though Hader is still an executive producer on that series, which will air a fourth season in 2022, he no longer is involved in the day-to-day running of the show). “Bill turned many, many, many things down,” Mulaney says. “I remember thinking, ‘Bill’s going to do something and I wonder what it is.’ He just waited till this perfect moment to do Barry. Sometimes being selective gets a bad rap. People think you’re Hamlet or some shit and just procrastinating and you’re afraid of making a decision. But Bill’s an excellent example of someone whose sensibility was so fine-tuned that he had absolutely every right to be.”

Hader is personable but not social, Mulaney says. “He’s super friendly, a very kind person, but he would love to take a book and go in the other room,” Mulaney says. “There’s this really endearing quality to him that is like, he’s still a kid with parents and two sisters who doesn’t want to go outside in Tulsa and wants to go downstairs and watch DVDs. I wouldn’t call him a loner, but he likes to be alone.”

In 2018, Hader and writer-director Maggie Carey, the mother of his three children, divorced. He has since dated actresses Rachel Bilson and Anna Kendrick but declines to talk about his dating life to protect the privacy of his daughters, who are 12, 10 and 7. “They just want me to be their dad,” he says. “They just want me to sit and watch Encanto over and over and over again. So that’s what I do.” Hader says he worried about the impact the stress of the pandemic would have on his kids. “Maggie and I were just trying to keep them calm,” he says. “And then, weirdly, it was the other way around. They would really keep us calm.”

The rhythms of running Barry are a more natural fit for Hader than Saturday Night Live ever was, and he has acquired some tools from years of therapy for his anxiety, like letting go of what he calls “false truths.” Together with his childhood friend and Barry writer Duffy Boudreau, Hader has written a feature script, which he plans to direct but not star in. He’s gotten some script notes from industry colleagues who once would have made him “spazzy,” Alfonso Cuarón and Rian Johnson.

While Hader still regards these filmmakers with awe, he says he no longer barrages them with questions. “It’s like going up to somebody who’s married and you’ve never been in love before. And you’re like, ‘How do you fall in love? What’s that like?’ Once you fall in love yourself, you’re like, ‘Oh, I have my own way of doing this thing.’ It takes the sheen off of it. ‘Oh, it’s that? Oh.’ The mystery’s gone.”

This story first appeared in the March 30 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter