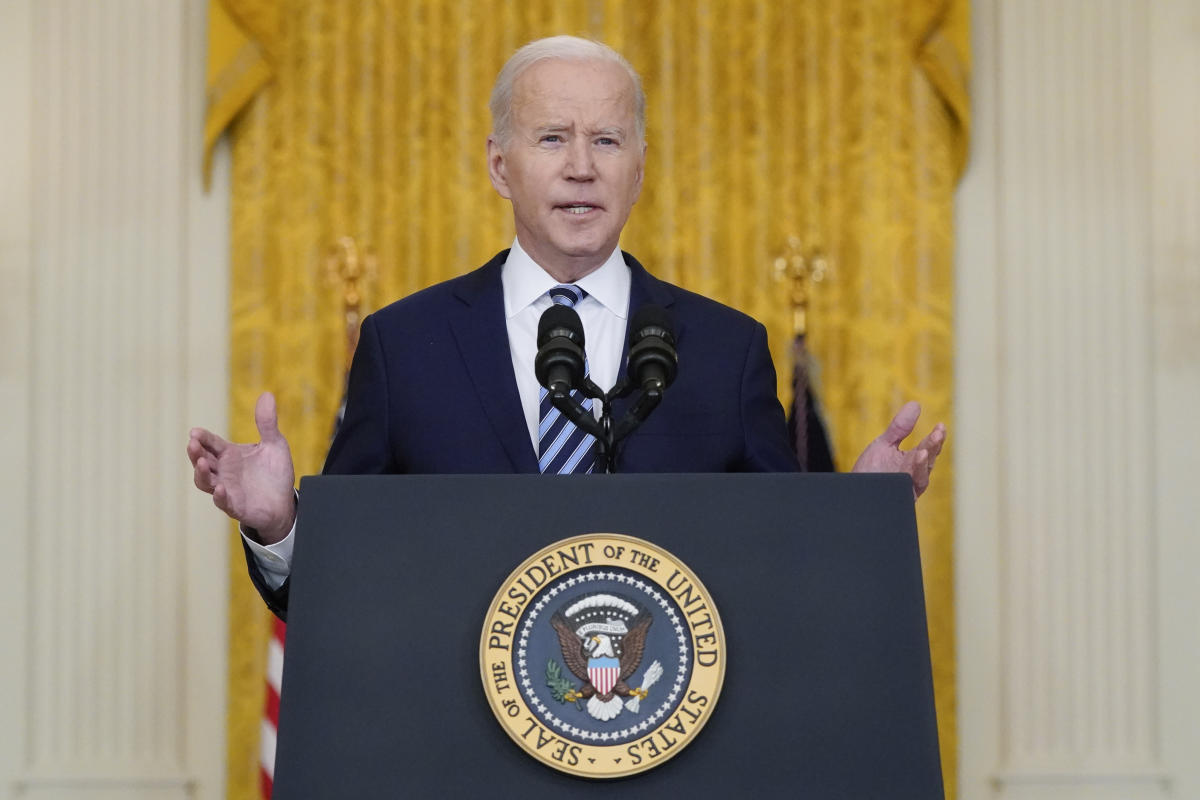

WARSAW, Poland — They were among the final few words of a carefully crafted speech. But they strayed far from the delicate balance that President Joe Biden had tried to strike during three days of wartime diplomacy in Europe.

“For God’s sake, this man cannot remain in power,” Biden said Saturday, his cadence slowing for emphasis.

Sign up for The Morning newsletter from the New York Times

On its face, he appeared to be calling for President Vladimir Putin of Russia to be ousted for his brutal invasion of Ukraine. But Biden’s aides quickly insisted that the remark — delivered in front of a castle that served for centuries as a home for Polish monarchs — was not intended as an appeal for regime change.

Whatever his intent, the moment underscored the dual challenges Biden faced during three extraordinary summit meetings in Belgium and an up-close look at the war’s consequences from Poland: keeping U.S. allies united against Putin, while at the same time avoiding an escalation with Russia, which the president has said could lead to World War III.

To achieve his first goal, Biden spent much of the trip drawing the world’s attention to Putin’s atrocities since he started the war Feb. 24. He urged continued action to cripple the Russian economy. He reaffirmed America’s promise to defend its NATO allies against any threat. And he called Putin “a butcher,” responsible for devastating damage to Ukraine’s cities and its people.

Dmitry Peskov, the Kremlin spokesperson, said Putin’s fate was not in the hands of the American president. “It’s not for Biden to decide,” Peskov told reporters after Biden finished speaking. “The president of Russia is elected by the Russians.”

Even as he made it his mission to rally his counterparts, Biden and his aides were determined to avoid taking actions that Putin could use as pretexts to start a wider, even more dangerous conflict.

“There is simply no justification or provocation for Russia’s choice of war,” Biden said earlier in his speech Saturday night. “It’s an example one of the oldest human impulses — using brute force and disinformation to satisfy a craving for absolute power and control.”

In closed-door discussions at NATO and with the leaders of more than 30 nations, Biden repeatedly vowed not to send U.S. troops into combat against Russia. And despite desperate pleas for additional help from Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Biden remained opposed to using NATO or U.S. fighter jets to secure the country’s airspace from Russian attacks.

Biden’s trip, which began Wednesday, came at a pivotal moment for his presidency and the world, amid the largest war in Europe since 1945 and a mushrooming humanitarian crisis. Both are testing the resolve and cooperation within the NATO alliance after four years in which former President Donald Trump cast doubt on its relevance and pushed a policy of America First isolationism.

For most of his foray abroad, Biden succeeded in staying on message, according to veteran foreign policy watchers — a reality that made his last-minute comment about Putin’s future even more striking.

“That message of unity is exactly what Putin needs to hear to convince him to scale back his war aims and end the brutality,” Charles Kupchan, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations. “It’s what Ukrainians need to hear to encourage them to keep up the fight. And it’s what Europeans need to hear to steady their nerves and reassure them that the United States is fully committed to their defense.”

And yet, the president ended his trip Saturday and returned home with few concrete answers about how or when the war will end — and grim uncertainty about the brutal and grinding violence still to come.

A top Russian commander on Friday appeared to signal that Moscow was narrowing its war aims, saying that capturing Kyiv, Ukraine’s capital, and other major cities was not a priority. Col. Gen. Sergei Rudskoi, chief of the Main Operational Directorate of the Russian military’s General Staff, said in a public statement that the military would instead concentrate “on the main thing: the complete liberation of the Donbas,” the southeastern region that is home to a Kremlin-backed separatist insurgency.

Administration officials say a Russian withdrawal to Donbas would amount to a remarkable failure for Putin, who has drawn international scorn for his invasion and has plunged the Russian economy into disarray under the weight of global sanctions.

If Putin decides to limit the scope of the fight, it would pose new diplomatic challenges for Biden, who has used the horror of all-out war to rally the world against Russia’s aggression. That could prove more difficult if Putin decided to move some of his forces back — whether as a real retreat or a strategic feint.

For the moment, however, large portions of Ukraine remain under siege while the country’s forces have mounted a fierce resistance.

On Saturday, even as Biden prepared to deliver his speech, Russian missiles slammed into Lviv, a city in western Ukraine not far from the Polish border. The missiles hit at or near what is believed to be an oil storage facility, and thick black smoke billowed over the city. At least five people were injured.

Putin’s thinking remained murky as Biden boarded Air Force One on Saturday night for the flight back to Washington, complicating his administration’s calculus as it looks for ways to keep the pressure on Russia without going too far.

It all adds up to a tricky task for Biden, who came into office determined to end America’s 20-year war in Afghanistan and now faces the challenge of managing the response to another war.

He has received high marks — even from Republicans — for sending more than $2 billion in military and security aid to Ukraine, bolstering its ability to fight off Russian forces. And he has joined European leaders in imposing crippling sanctions on the Russian economy, putting immense pressure on the Russian leader’s most ardent backers.

During Biden’s visit to Brussels, NATO announced the redeployment of additional forces to member countries closest to Russia, an effort that Biden said would deliver a message of resolve to Putin.

The president also announced $1 billion in humanitarian aid for Poland and other nations who have taken in 3.5 million people fleeing the fighting in Ukraine. Biden said the United States would open its borders to 100,000 Ukrainian refugees.

“Visible American leadership is no longer taken for granted in Europe,” said Ian Lesser, executive director in Brussels for the German Marshall Fund. “In this sense, the president’s trip has made a significant impression.”

But the president also drew criticism from Zelenskyy for refusing to enforce a no-fly zone over Ukraine.

“Their advantage in the sky is like the use of weapons of mass destruction,” Zelenskyy told Biden and leaders of other NATO countries during their closed-door meeting Thursday. “And you see the consequences today. How many people were killed, how many peaceful cities were destroyed.”

Biden faced the limits of European action when he put to his allies the question of curtailing Russia’s ability to profit from the sale of its oil and gas. Europe gets a large percentage of its energy from Russia, and Biden once again found a deep reluctance to making any decision to cut off that lifeline.

Instead, the president announced a longer-term plan to help wean Europeans off the use of Russian fuel.

Jeremy Bash, who served as a top adviser at both the Pentagon and the CIA under former President Barack Obama, called Putin’s war a “a geopolitical earthquake” and a “once-in-a-generation contest” that has forced Biden to adapt quickly to a rapidly changing security and diplomatic world.

“President Biden is now a wartime commander-in-chief waging four wars at once,” Bash said Saturday. “An economic war, an information war, likely a cyber war, and an unprecedented indirect military war against Putin. And so far, Putin has been unable to achieve a single one of his objectives.”

Several of the administration’s most ardent supporters in the foreign policy world quickly chided the president for seeming to seek Putin’s removal. Richard Haass, president of the Council on Foreign Relations, called it a “bad lapse in discipline that runs risk of extending the scope and duration of the war.”

While U.S. officials still insist their goal is not regime change in Moscow, even the president’s top national security advisers have made clear they want Putin to emerge strategically weakened.

“At the end of the day, the Russian people are going to ask the more fundamental question of why this happened and how this happened,” Jake Sullivan, the president’s national security adviser, told reporters on Air Force One on Friday, before the president’s speech. “And we believe that, at the end of the day, they will be able to connect the dots.”

Sullivan added: “These are costs that President Putin has brought on himself and his country and his economy and his defense industrial base because of his completely unjustified and unprovoked decision to go to war in Ukraine.”

© 2022 The New York Times Company