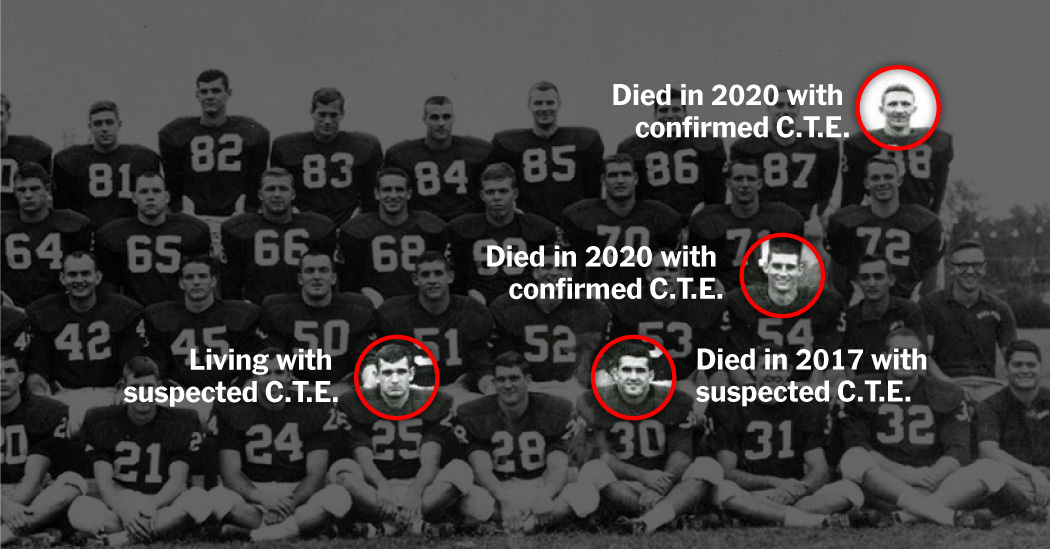

The repercussions of C.T.E., which cannot be definitively diagnosed until after a person’s death but is routinely found in football players when researchers are allowed to conduct post-mortem examinations, can be jarringly conspicuous: episodes of confusion and memory loss, spasms of anger and argument and steep declines in communication and decision-making skills.

“You just see them really turn into someone totally different,” said Heike Crane, the widow of Paul Crane, who played center and linebacker for Alabama and ultimately developed C.T.E. before his death in 2020.

About 60 years ago, though, long before C.T.E. was a recognized risk, football at a place like Alabama was a waypoint to wealth, stature and envy. Even now, amid their agony, players and their families are often reluctant to wish football away from campuses or American culture. Change the sport, some say, but keep playing it.

Head Injuries and C.T.E. in Sports

The permanent damage caused by brain injuries to athletes can have devastating effects.

For many of the men who played, health threats were worthy personal sacrifices back then.

“I was from kind of a small town in Tennessee,” said Steve Sloan, an Alabama starting quarterback in the 1960s who was later the athletic director there and the football coach at Duke, Mississippi, Texas Tech and Vanderbilt.

“I wanted to get a scholarship, and I wanted to get a degree, and if it took hits in the head, then it was all right,” said Sloan, who said he had not experienced the severe symptoms of C.T.E. “I’m just lucky.”

The Decline of a Merry Life

Much like Sloan, Ray Perkins came to Tuscaloosa in search of a life beyond the rural town where he was raised. Bryant, who won six national championships before his death in 1983 and whose name is now on the 100,077-seat campus stadium, was the draw.