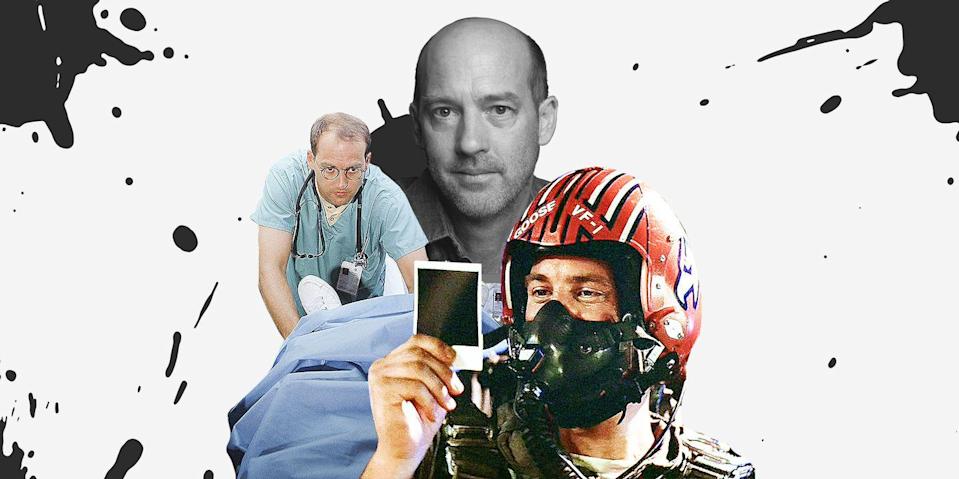

You tend to start a talk with Anthony Edwards in the middle, like you’re picking up a conversation you’d left unfinished a day or two before. It’s partly because he’s naturally charming and gracious, of course, but it’s more than that. He’s familiar, a face who’s always been been there, a genial neighbor or a friend of an older brother who’s around the house a lot. “When I do get recognized,” he says, “it’s generally just a nod and a how are you doing.” He’s such a steady, reassuring presence, it’s easy to forget you actually haven’t seen him in a while. “I took such a time out that the things that people know me for, Top Gun and ER and all that, those were a long time ago. I get that classic thing of like, oh my God, my mom and dad used to watch you,” he says, laughing. “Or my grandmother.”

He is older now; Goose and Dr. Greene and Gilbert from Revenge of the Nerds all turn 60 this year. And he has been gone for a while, indeed; he stepped back in the early aughts to raise his kids, and then again a few years ago to heal from a trauma he’d endured in his youth, a situation he revealed publicly in 2017. That process has led him back to the thing he’s known the longest, which is acting. “It’s funny how this thing that gave me such joy when I was a kid, being in the theater and working with people has really been a through-line to help me through everything.” He’s back in a couple of timely projects: Inventing Anna, out today on Netflix, about the story of New York grifter Anna Delvey, and WeCrashed, Hulu’s take on the creators of WeWork. Processing his own trauma has also made him an activist; through his non-profit organization 1 in 6, he can use his familiarity and charm to connect with and help heal fellow survivors of sexual abuse. “My wife and I talk about this a lot,” he says. “After a while, you learn to use your tricks for good.”

Right now, he’s in Atlanta, shooting an episode of the upcoming anthology Tales of the Walking Dead. Uh-oh. A major reason that you feel connected to Anthony Edwards, that you maybe even have the urge to protect him from zombies, is that you’ve seen him die a few times. Most notably in the middle of Top Gun, breaking poor Meg Ryan’s heart, sending Tom Cruise down a guilt spiral only silhouetted love-making to the sounds of Berlin could set right, making even Iceman drop the mask for a moment. The movie suddenly gets serious, the stakes get higher, and it only works because you like Anthony Edwards so much. You almost didn’t get him. “The studio really wanted a comedian for the role,” Edwards tells me, “and Tony Scott was like, ‘No, I want an actor.’” Tony Scott got his way, and Anthony Edwards got a message: “Just before shooting, I got a basket from Paramount, with a note on it: Goose may not be wise, but he is ALWAYS FUNNY, all caps, underlined. I was like, where in the script is that?”

Edwards himself was ambivalent about the movie at first. “It was not a script that I read and went like, we really need to tell this story. I was raised in this really hippy-dippy family, and glamorizing the military was just not where I came from.” It did make generations of kids want to enlist—to this day, people tell him they joined the military because of that movie—but it was something he viewed as a career move rather than an artistic one. “Look, they did it beautifully and it’s great and it changed my life in a lot of ways, but there’s nothing in there that makes me as actor go, God, yes.”

Pre-Top Gun, Edwards bounced around Los Angeles as a student at USC and a working actor. He got his first big break in the family sitcom It Takes Two, playing the son of Patty Duke and Richard Crenna, brother of a young Helen Hunt, who’s still one of his closest friends. The show didn’t last, but it vaulted him into an echelon of busy young actors. Well, near that echelon: “I wasn’t quite drawn into the whole world of what was going on with Tom [Cruise] and Rob [Lowe] and Emilio [Estevez]. I’m sure part of me really wanted to be in there, but it wasn’t my journey.” Edwards took a more pragmatic approach: “I would just pursue everything, and when things got turned down by other people, that’s where I was. I was definitely sloppy seconds.”

One role he did not get was Gib, the lead in the criminally overlooked Rob Reiner romantic comedy The Sure Thing. He and Mare Winningham—stick a pin in that name—screen-tested for the roles that eventually went to John Cusack and Daphne Zuniga. But good things came out of it: Reiner cast him as Lance, Cusack’s best friend, the guy who sets the plot in motion. And that screen-test set something in motion as well; again, more on that later. For now, watch The Sure Thing on YouTube, somehow the only place it’s streaming.

In Inventing Anna, Edwards plays Alan Reed, “I’m the lawyer who’s representing her, helping her to build this big thing. I’m doing a lot of vouching for her and believing in her when I don’t have all the information I really need, because she’s so charismatic. Here’s this young energy that’s able to manipulate and control people by telling them what they want to hear.”

The subjects of trust and truth and manipulation are areas Edwards is ready to explore in his work, because they’re areas he’s explored in painful and public ways in his life. In 2017, Edwards revealed that he had been the victim of sexual assault by his mentor. “It happened to me when I was 13, 14 years old, and I didn’t face it until I was 52.” That’s par for the course, he says. “The average amount of time for men to divulge sexual abuse, or even to start to look at it themselves, is between 20 and 40 years. That’s because you isolate when you’re in this situation, you don’t share, you don’t talk, you don’t want to hear about it, because classically, when young people are abused or assaulted sexually, it’s done by someone who they trust and love. That’s why we’ve heard and will continue to hear about in the trust that is betrayed in the Catholic Church or in the Boy Scouts.”

“A kid’s job is to fall in love. That’s what children are supposed to do, they’re supposed to love things. So when that person who supposed to love you hurts you, the first thing that happens is you think it’s your fault. You think you must have done something wrong.” And when this happens in a person’s formative years, the trauma gets fused into the person. “There’s just so much shame involved in it, and it manifests in other ways: self-destructive behaviors, alcohol, drugs, control, rage, anger, all the different things that probably draw people into 12-steppy type recovery programs.”

For Edwards, it manifested in a way that actually became his superpower. “I think I overachieved in a lot of ways,” he says. “I got really super hyper focused. It’s a perfect setup for raging codependency, and raging codependency is a great place for actors. A codependent will go into a room and assess everything that’s going on so they can figure out how to survive in it.” And if Edwards has always gotten by with a touch of aw-shucks charm, that too is a coping strategy. “I became so insanely self deprecating. If you look back at the six or seven Lettermans I did, every story is like, oh no, I’m nothing, I’m nothing, I’m nothing. It was constant.” Even here, now, telling me this, he wants to put me at ease, to minimize. “As a disability, it’s a very nice one, it just doesn’t necessarily serve the individual.”

It was having children of his own that made him take a look at his abuse. “There is something spectacular that happens to people who are lucky enough to become parents, an undeniable feeling in relationship to unconditional love. There’s such empowerment in that knowing that you would love somebody that much.” And at around this time, he ran into his abuser in an airport. “When I saw that person who had hurt me, I was just like, no, that doesn’t compute in the world the way I’m seeing it now. The idea of that kind of thing happening to my son was like…” he looks for the words. “You feel that.” Edwards confronted his abuser. “He just filled me with all kinds of stories of how, it was a dark part in his life, and he was sorry it happened, but it was all out of love, and he’s changed, and I bought it.” Not long after, this man was named in relation to the Bryan Singer scandal. “That’s where the rage came.”

Edwards channeled his rage into a first-person Medium post, in which he told his story and named his abuser. “I’d been working on a Menendez brothers project,” in 2017’s Law & Order True Crime: The Menendez Murders, “and if I was going to talk publicly about abuse and tragedy in that family, how can I do it and not be like, well, I understand what abuse is about.” He was a little fearful upon hitting publish, but the main emotion was relief. Right away, other men began to tell him their stories of abuse. “Men classically have minimized what happened to them for their whole lives, because that’s the only way they could get through it because the fear facing it is too much.”

[embedded content]

In order to foster more openness and healing around sexual abuse, particularly in men, Edwards started the non-profit organization 1in6.org. “One in six is the very moderate estimate of men who were sexually abused or assaulted before the age of 18. That puts the number at about 27 million American men walking around who don’t talk about it.”

When a familiar face shares his story, it makes it easier to share your own.

Which brings us back around to the role both he and Paramount were not quite sure of. “Goose is now a great entree for me to go in and talk to 3 or 400 men and women about taking shame and stigma away from the fact that they were possibly abused when they were kids. I spent so many years worrying that I’ve been promoting violence and this kind of jingoistic America that gets us into trouble, but now in the work that I’m doing with male survivors of sexual abuse, the military’s been our biggest supporter and advocate. They understand post-traumatic stress. So there’s a flip-side to it. As my dad would say: so late, we get smart.”

Some good things take time. Edwards and Mare Winningham didn’t get those lead roles in The Sure Thing in 1984, but they did do Miracle Mile together in 1986, a movie real film buffs still stop him to talk about. They both got married and had kids and remained friends through their divorces before finding themselves living in New York City at the same time. They eloped at the end of last year, just the two of them and an old friend to officiate. “We’re too old to throw weddings,” he says. But not too old for eight shows a week: “She’s doing Girl from the North Country on Broadway and she’s just spectacular. She’s an amazing singer and she’s a wonderful actress and she’s an incredible person.”

Anthony Edwards will turn 60 this July. “I go, wow, how did that happen? And then I look and it happened because of the grace of a lot of really, really lovely people and the relationships in my life, good and bad, really appreciating them. It’s what we talk about in this Walking Dead thing: that we can never isolate. Isolation is death.” And that’s where he leaves it: this guy I’ve never met who I’ve known forever, this self-deprecating life-saving activist, this Goose. “The only way we really survive is by connecting.”

You Might Also Like