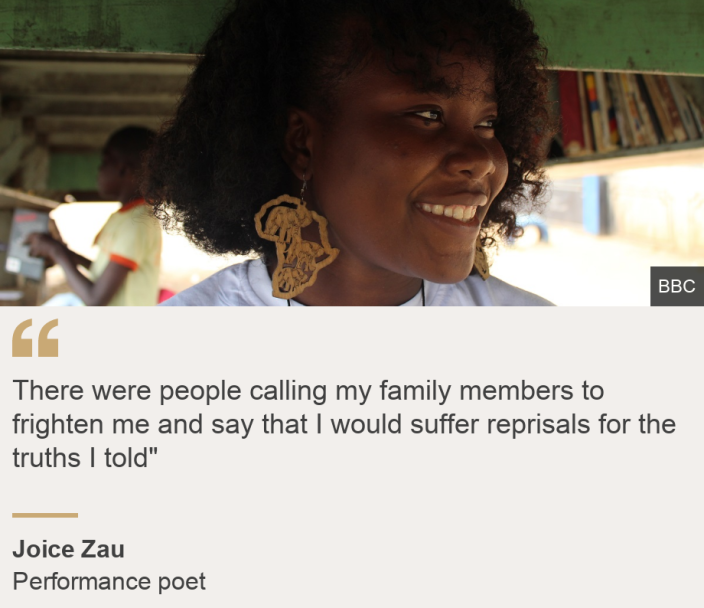

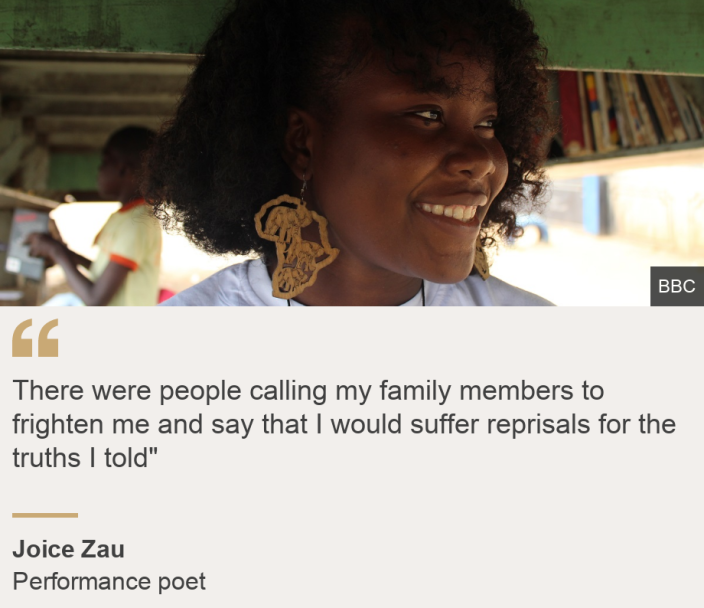

Despite describing herself as a shy person, Joice Zau is one of the most high-profile figures in a new spoken-word movement spreading across Angola, and her talent has even led her to represent Brazil in international competitions.

Her sweet yet assertive voice first captured the attention of many after a slam poetry performance was uploaded on Facebook in 2020.

Zau was performing at Slam Tundavala, a spoken-word competition aired by a private TV channel that aimed to promote and celebrate the creativity and freedom of expression of young Angolan artists.

She decided to perform what she called a “demonstration of her artistic sensitivity” given the social and political pressures that Angola was going through at the time – during the pandemic many freedoms were curtailed by the local authorities.

“They deceive us with slogans,” she declared in her poem talking about politicians and their failure to address Angola’s glaring inequalities.

It is unfair

That the chapters of a Machiavellian past are perpetuated to this day like ‘fine dust’ that flows into the indigestion of our stomachs

It is unfair

That the flag we once raised continues to shed the blood of our current pains and evaporate our dreams

Extract from 2022 Vais Gostar (You will like it)

Despite some changes after President José Eduardo dos Santos stepped down in 2017 after almost four decades in power, speaking out in Angola can still be a dangerous thing to do.

This is why some saw Zau’s performance as an act of courage, but it was the 25-year-old’s passion and sincerity that made the moment.

She had spent the previous three years in near anonymity writing and performing, wishing she could inspire political change.

The poem’s title, 2022 Vais Gostar, literally means “You will like it” and is seen as an ironic threat to the governing MPLA party which is facing an election this year.

It was written in her now signature style of simple and direct language.

In it, she criticised what she called the “harmful governance” of the MPLA, which has been in power since independence in 1975.

Exploring current social issues in the oil-rich nation, such as poverty and the lack of basic services, she criticises the Dos Santos regime, but says the problems live on under his successor João Lourenço.

But what was only meant to be a cry for freedom on a TV spoken-word contest became a feminist symbol of artistic resistance and caused deep fear and insecurity for Zau.

“There were people calling my family members to frighten me and say that I would suffer reprisals for the truths I told,” Zau says.

“I felt scared and was advised not to leave my home for more than a week.”

Despite some progress in terms of freedom of expression and peaceful assembly in the country, many artists still feel the need to think twice before openly criticising the authorities.

“We are still living in a dictatorship. The law says we can express ourselves, but the reality is completely different.

“We thought that with a new president in 2017 things would be different, but it was all political theatre,” Zau tells the BBC.

The dream and the reality

Born in a village surrounded by the Mayombe Forest in the Angolan exclave of Cabinda, she says she grew up swimming in the rivers that run through the rich forest, exploring its innermost secrets.

She describes her childhood as “happy and peaceful”, living in the middle of the forest, believing it has somehow shaped her and her views of the world.

But it was in the country’s capital, that this second daughter of six siblings discovered her passion for poetry and delight for spoken-word.

“Cabinda is a province geographically separate from Angola. So the dream that people from Cabinda have about going to Luanda is like the dream Brazilians have of going to the US,” she says.

Zau arrived in Luanda in 2014 to study electrical engineering, as Cabinda did not have universities offering her chosen degree at the time.

But she did not find what she had hoped for in the capital city.

“The real Luanda wasn’t as perfect as the one in the Utopia I had built in my head for years.”

Social inequality was one of the main reasons that led her to start writing poems that questioned the authorities and their political decisions.

After her video went viral, several international invitations began to arrive.

She won the 2021 Lusophone Female Spoken Poetry Championship and was a finalist in the Guilhermina Slam Contest, which both took place in Brazil.

She also won the Brazilian national contest, Slam Brasil, last year which meant she qualified to represent Brazil in the Copa América de Slam – one of the main events on the spoken poetry calendar in Latin America.

“Art has a tendency to take us down paths unimaginable for our minds,” she says.

This year, Zau will represent Brazil in two international spoken-word competitions – one in France and another in Belgium.

“It’s a strange feeling to represent a country that isn’t mine,” she says, laughing.

“But when I’m declaiming, I feel like I’m representing Angola. And even when I’m representing Brazil in a competition, they always make it clear that I am Angolan, so people always know where I come from.”

‘Women move this country’

In Angola, the spoken-word movement is fairly recent and like most other public activities, it started out as a heavily male-dominated space.

But Zau wants the contribution of women recognised.

“Women are what move this country. And we can see proof of that in the informal markets, where most of the people doing business are women and that says a lot given the economic contribution this sector has in our lives,” she says.

And she is not going to keep a low profile.

Her poem Between Peace and Love, I prefer Love encapsulates her determination not to keep quiet for the sake of social order.

I absolutely hate peace

Screw it, morals and good customs, the laws of physics that govern nature in time and space, I hate peace and I’m not of peace

Peace doesn’t mean anything to me, peace doesn’t represent me

Peace, a rag to a stained social fabric, peace is feigned

Peace, pretends that freedom springs, while it makes us products on a conveyor belt and controls us through antennas

Peace, wreaks havoc in winter, comes with a smile that opens like a flower in spring and corrupts our cries for justice

Extract from Between Peace and Love, I prefer Love

On the elections scheduled for August this year, Zau is hesitant to speculate about what could happen.

“People are still too afraid to express themselves politically. People are afraid to think, to say what they think and to act.

“We still have a lot of work to do. We need to make people aware in order to awaken their lost civic and patriotic sense,” she says.