WASHINGTON — Two flamboyant pop culture icons take center stage at the staid, tradition-bound Supreme Court on Wednesday as the justices weigh whether artist Andy Warhol infringed on the copyright of a photographer’s image of the rock star Prince when making a series of his signature silkscreen prints.

During the oral argument, the court will consider a legal question of considerable interest to people in all kinds of creative industries, including television, film and fine art, on how to define whether new work based on an existing one is “transformative” — meaning it does not violate copyright law. Under the law, limited “fair use” of a pre-existing artwork is lawful in certain contexts, including when the new work conveys a different meaning or message.

While Warhol, one of the leading pop artists of the 1960s, has been credited with the expression that everyone in the future will get 15 minutes of fame, the oral argument could last for as long as two hours.

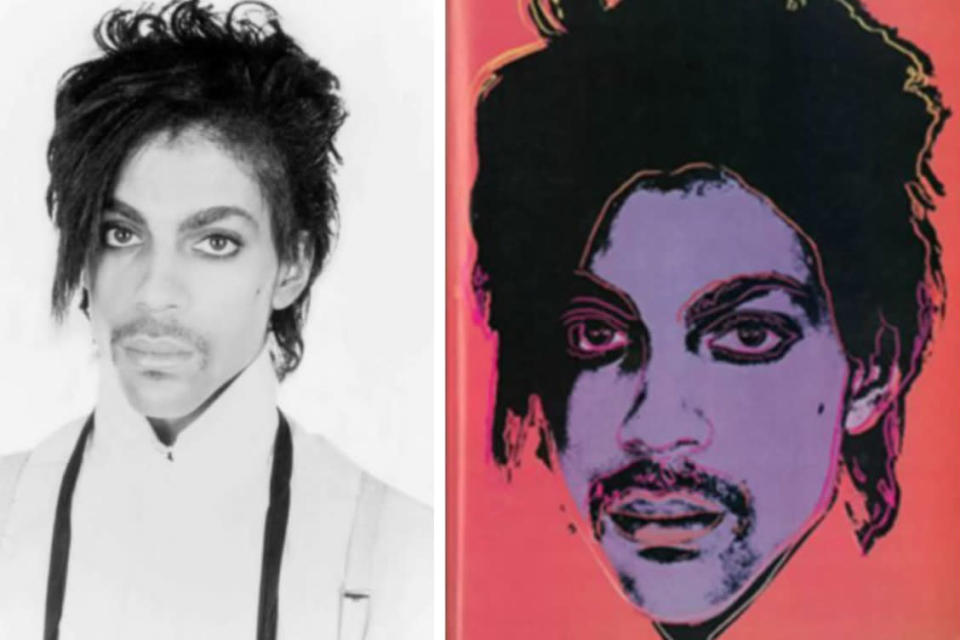

Noted photographer Lynn Goldsmith sued over Warhol’s use of her 1981 photograph of then-rising star Prince before he attained global fame on the back of hits like “Little Red Corvette” and “When Doves Cry.” As part of an arrangement with Vanity Fair magazine three years later, Warhol created a series of silkscreen prints as well as two pencil sketches based on Goldsmith’s image. While the original photo, a portrait of Prince, was black and white, the silkscreen prints superimposed bright colors over a cropped version of the original photo. The style was similar to other famous Warhol works, such as his portraits of Marilyn Monroe.

Under a license it had obtained from Goldsmith, Vanity Fair used a Warhol illustration based on the photo in its November 1984 issue without any problems arising. But Goldsmith said she was not aware that Warhol had created other images that were not licensed, a fact she only became aware of after Vanity Fair publisher Conde Nast used a different image as part of a 2016 Prince tribute immediately after the rock star’s death.

Warhol himself had died in 1987, and the relevant works and copyright to them are now held by the Andy Warhol Foundation, which permitted Vanity Fair to use the image in 2016. Goldsmith was not credited.

The following year the issue ended up in court, with Goldsmith and the foundation suing each other to determine whether Warhol’s image constituted fair use.

In 2019, a federal judge ruled in the foundation’s favor, saying that Warhol’s images were transformative because, while Goldmith’s photo showed a “vulnerable human being,” the Warhol prints depicted an “iconic, larger-than-life figure.”

The foundation sought Supreme Court review after the New York-based 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of Goldsmith in March 2021. The appeals court faulted the district court for focusing on the artist’s intent, saying a judge “should not assume the role of art critic.” Instead, a judge must examine whether the new work is of a completely different character to the original, the court said. It must, “at a bare minimum, comprise something more than the imposition of another artist’s style on the primary work,” the court added.

Various interested parties have filed briefs advising the justices on what approach to take, including movie and music industry groups, educational institutions and individual artists. (Universal Pictures, a division of NBC News’ parent company NBCUniversal, is a member of the Motion Picture Association, which filed a brief in the case in support of neither party.)

The parties’ approach to the legal question depends in part on to what extent their work relies on protecting their own copyrighted material as opposed to making fair use of other people’s copyrighted content.

A relevant Supreme Court precedent cited by both sides is a 1994 ruling in which the court held that it was fair use when rap group 2 Live Crew created a song called “Pretty Woman” that was a parody of Roy Orbison’s “Oh, Pretty Woman.”

Like the parody song, Warhol’s additions created something new that conveyed a different message, the foundation’s lawyers argue.

Goldsmith’s lawyers point to other language in the 2 Live Crew ruling that said a fair use argument is undermined if there is a risk that the new work will supersede the original and undercut its market value.

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com