Andrew McCarthy wasn’t really a member of the Brat Pack, but he definitely played one in the press. In the summer of 1985, New York magazine journalist David Blum accompanied some of McCarthy’s St. Elmo’s Fire co-stars — including Emilio Estevez, Judd Nelson and Rob Lowe — during a night out on the town. The resulting article coined the collective name that would haunt an entire generation of young Hollywood actors … even those that weren’t present on the evening in question. That’s what happened to McCarthy, who is referenced once in the article in absentia. And that single mention was enough to make the then-22-year-old actor a Brat Packer for life, like it or not.

And to be clear, he didn’t like it … at least, not back then. “It took me years to come to terms with it,” McCarthy tells Yahoo Entertainment, adding that he felt “swallowed” by the association when it happened. “The ‘Brat Pack’ thing is warm and fuzzy now, but at the time, it was a very scathing thing. The public perceived us as being the ultimate in-group, and while that certainly wasn’t the actuality, perception is everything. There was something about it and it very quickly became embedded in the culture.”

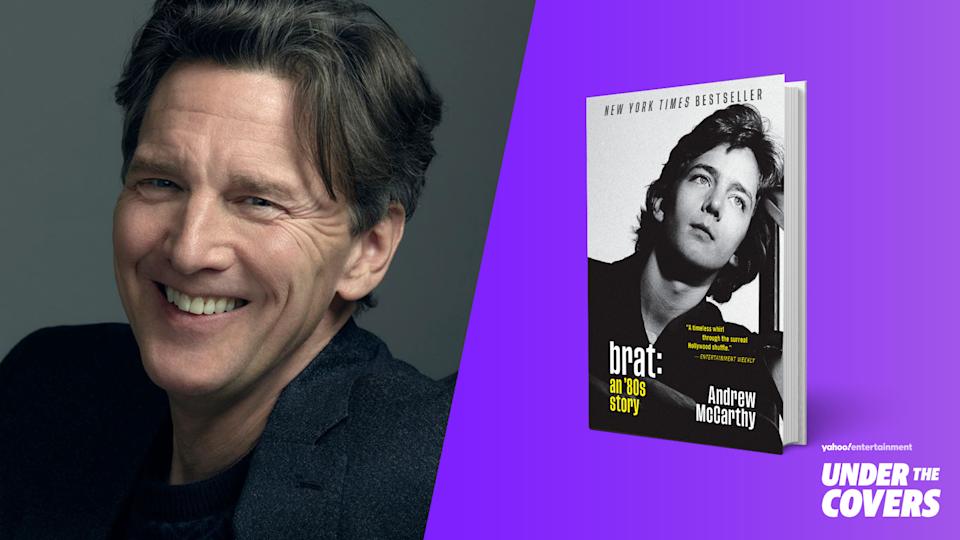

Almost four decades removed from the Brat Pack era, a 59-year-old McCarthy confronts that tumultuous time head-on in his memoir, Brat: An ’80s Story, which arrives in paperback on May 10. The book traces his New Jersey childhood to his struggling actor days in Manhattan to that sudden burst of stardom that ignited with St. Elmo’s Fire and continued in hits like Pretty in Pink, Mannequin and Weekend at Bernie’s — movies that serve as touchstones for the audience that grew up wanting to be part of the club that its actual members would have rather renounced.

“Those movies are meaningful to a generation of people, because they remind them of their own youth,” McCarthy observes. “When they talk to me about the Brat Pack, they’re really talking about that own moment in their youth when they were in their basement or their friend’s basement watching one of my movies for the 10th time. It’s about them, and I’m just the avatar that represents that to them.”

Part of McCarthy’s mission with Brat is to reveal more about the person behind the avatar. During the course of the book, he describes his difficult relationship with his father, whose volatile temper resulted in lifelong tension between the two. (McCarthy’s father died in 2016.) And he describes how his reliance on drugs and alcohol deepened as his star rose — a challenge that some of his fellow Brats famously faced as well.

As McCarthy speculates in the book, had the Brat Pack been an actual pack, they might have been able to find a way through their problems together. As it was, the scorn that the New York magazine article engendered forced the already loose collective even further apart. “I wonder what would’ve been different if he had stuck together,” McCarthy muses. “Maybe people still would have been like, ‘Shut up.’ That one magazine article burned deep.”

But the Brat Pack burn ultimately faded on its own. By the late 1990s, McCarthy was an active presence in independent film and television, both in front of and behind the camera. As his directing career took off, he put acting on pause, only recently returning for recurring roles on the just-canceled NBC series Good Girls and Fox’s medical procedural, The Resident. Asked if he’d consider helming a Brat Pack streaming series — one that would reunite all the O.G. Brat Packers — McCarthy just laughs. “We’d have to have a good story! A movie like St. Elmo’s Fire would be a limited series now.”

Reading Brat, I got the sense that you often felt at a remove from the events of those years. How much of that is simply due to you looking back on your life now and how much of that distance did you experience at the time?

It’s interesting. The voice I wanted for the book wasn’t this immersive “and now this happened” sort of thing. I wanted it to feel more like, “You want to know what it was like? Sit down and I’ll tell you.” As the reader, I wanted you to feel like you’re in it, then pulled back from it and then going in it again. So that was a conscious choice, but I also did feel very distant from things while they were happening, too. I think that’s just a protective device that we can have: There were a lot of times in my youth where I felt at a remove from events. That was part of my character in St. Elmo’s Fire — he was in it, but he also felt separate from it.

As you mention in the book, you weren’t there the night that the Brat Pack was born. Have you ever thought about how you might have acted if you had been out with your co-stars?

Oh, I have no idea. Knowing me, I probably would never have gone. It all seems so wonderfully naive looking back at it now. It’s like, “What were you thinking?” I recently talked to Emilio for the first time in a decade and I asked him that. He was just like, “I wasn’t thinking! I was part of an ensemble, so I wanted [David Blum] to meet the ensemble.” And the writer certainly could have written it that way; he just chose to take a different tack and present them in a certain light that may not have been how it actually was.

Your father plays a big role in the book: You talk a lot about your troubled relationship with him and his anger issues. Looking back, do you have a better sense of the root cause of that anger?

Like so many people, my father had a massive amount of unacknowledged fear, and when people are dealing with that kind of fear it tends to morph into anger. He was from a different generation in terms of not being self-examining. When I was a young guy, I was afraid of his anger and I just ran from him. I didn’t understand it. There were three things that dominated my life in the ’80s: one was movies, one was alcohol, and the third was my father, and to write about any two without the third would be like a two-legged stool, you know?

He wasn’t in the first draft of the book, but then I realized that if I was going to talk about certain things, I was leaving out a big piece of the puzzle by not also talking about him. So I went back and threaded him through it, and I found that clarified things for me about my past. I reconciled with my dad before he died, and that was lovely and nice, but writing about it really helped me clarify how impactful he was on my youth.

What’s an insight into him that you experienced writing the book that you wouldn’t necessarily have had at the time?

Just the amount of terror that he lived under and wasn’t even aware of. Fear is a very cunning foe, because it masquerades as a lot of other things. The only thing fear will not do is admit its own existence, because that feels emasculating somehow. My father was operating under mountains of fear that he didn’t have the wherewithal to even address because he wasn’t aware of it. So it just morphed into anger, which is standard operating procedure for a lot of men.

I have operated with a lot of fear in my life as well, and acknowledging that was very liberating. Once you’re not sort of bound by that thing, you can look at it with compassion and love. I love my father much more freely now than I did when I was in my twenties. As I say in the book, we didn’t solve our past — we just put it down. There was great freedom in that. For a long time, he was a thing to be avoided or pushed against. Now, there’s nothing to push back against anymore: it’s just who he was.

As you mentioned, alcohol and drugs were a big part of your life in the ’80s. Did you dependence on them happen gradually, or was there one inciting incident?

Well, alcohol is also a cunning foe, and it just slipped up. For other alcoholics, it’s a much longer progression, but for me it only took several years. Luckily, I didn’t have the constitution to keep it up for that long. By 29, I was played out. With some people it can go on for decades, whereas I had maybe a half-dozen years where I was really not calling the shots in my life. At the time, it did feel like forever, and it certainly happened at a very public time in my life. But that also meant that it was so dominant that it had to be addressed — I couldn’t pretend it wasn’t an issue. So many alcoholics pretend to themselves and others that it’s not an issue; I wasn’t strong enough to do that.

That era of Hollywood was famous for its excesses. Did the industry play a role in enabling your addiction?

No, I just drank better vodka! [Laughs] But otherwise it had nothing to do with it. I drank because I had a propensity towards alcohol, not because I was in movies.

Was there a rock bottom moment prior to your recovery?

There were several, but I remember one moment in an L.A. hotel room where I’d been up all night. I just kind of cried for help and that cry didn’t feel like a whisper. After that, I called someone and said, “I need some help here.” That was the beginning of what changed my life. It’s not very dramatic, but then those things aren’t very dramatic. Only in hindsight do we attach that kind of significance to them.

[embedded content]

This year happens to be the 35th anniversary of Less Than Zero, which is one of the most famous ’80s movies about drug addiction. You tell a great story in the book about being Robert Downey Jr.’s minder during one night out on the town.

Yeah, the making of that movie was not a particularly joyful experience. It was a very dark story, for one. I was also in a dark place, and Bobby was well known to be in a dark place. But I’ve also had many people come up to me over the years and go, “That movie kept me off drugs,” which is nice. I wish it had done the same for me!

Were you and Downey taking drugs at the same time? Did you have the same dealer?

No, we didn’t. I never had any experience doing anything with Bobby. I love him — he’s lovely, charming and the sweetest guy in the world. But I never had any experience partying with Bobby. I was generally in my room alone in my own private Idaho, to quote a song of the day.

I was surprised to see that Less Than Zero isn’t currently streaming anywhere.

Oh, it isn’t? I think they must take them in and out of rotation. It’s a funny movie, and it doesn’t work, really, in my opinion. It certainly had nothing to do with Bret Easton Ellis’s book! While we were in the middle of making it, the national mood switched over to Nancy Reagan’s Just Say No era, so drugs — which had previously been thought to be hip — suddenly became the enemy. We actually went back and re-shot scenes of people flushing cocaine down the toilet and stuff like that. The movie and book were intended to be like, “This is what’s gong on,” without any real judgment. But the studio felt that had to inflict a message on the movie, to its detriment, I think.

Bret Easton Ellis essentially disowned it when it came out.

Well, there’s not a sentence from his book in it. I mean, Bobby’s character lives in the book! I think in time Bret is going to have affection for it, the way one does for these kind of weird ’80s things, but it certainly has nothing to do with the work that he did.

[embedded content]

Mannequin is also turning 35 this year, and it’s not streaming either. I still have the DVD fortunately.

Wait, you don’t have the VHS? [Laughs]

It took awhile, but I finally upgraded.

Mannequin has a good heart. It really is this open-hearted, sweet movie, and I have an affection for it because it doesn’t have a cynical bone in its body. It somehow works because it’s just so innocent. It’s a ridiculous movie, obviously, and could never be made today. The objectification of a woman who comes to life only for a guy would be railed against today. But it still feels sweet in a certain way. And people still like that song for some reason.

You mean you don’t crank the radio up every time it plays?

Sure I do — it’s great! But I think Starship did some better songs than that one.

[embedded content]

Watching Mannequin again now, the thing that jumped out to me is that it’s basically a comedy about respecting other people’s sexual kinks. Your character is walking around with a mannequin under your arm and vanishing into the bathroom with her, and everyone else is like: “That’s fine!” To your point, it has a sweet message.

I’ve never considered it like that. You’re right, though: It’s a very open-hearted, loving and tolerant movie in its way. And Meshach Taylor is fantastic as Hollywood — he’s doing his thing and our characters are great friends. It’s all very sweet, and not cynical or judgmental. It’s so un-’80s in that way.

Did Meshach Taylor have any concerns about playing Hollywood? It’s a character that could very easily become a flamboyant stereotype.

No, he just came in and did it! I don’t recall anyone ever questioning anything he did — they were just smiling. That character is a total stereotype, but Meshach played it was such tenderness and love. How could you not love him? [Taylor died in 2014.]

I know this comes up a lot, but I do have to ask about the original Pretty in Pink ending in which Andie ends up with Duckie, and not Blane. Thirty-six years later, do you think Duckie was the right guy for her after all?

No, don’t be ridiculous! [Laughs] It’s the only way for that movie to end, because it’s a fairytale. Andie had to get whatever she wanted, and that’s what she wanted, so it has to end that way. Look at Team Duckie over here.

[embedded content]

Hey, Duckie’s one of the original ’80s nerds, so we couldn’t not root for him back then!

I’m going to challenge Jon Cryer right now to a do-over. God bless him. [Laughs]

It doesn’t look like the original ending has survived apart from some behind-the-scenes footage. Do you recall any of your lines from that version?

Geez, I really can’t remember. What’s interesting is that people thought so little of the movie at the time, they didn’t bother to save that stuff. They just thought it would come and go! When we reshot the ending, I remember that I had a terrible wig on my head. I always joke that had they known we’d still be talking about the movie all these years later, they would have paid for a better wig!

Brat: An ’80s Story is on sale now at most major booksellers, including Amazon.