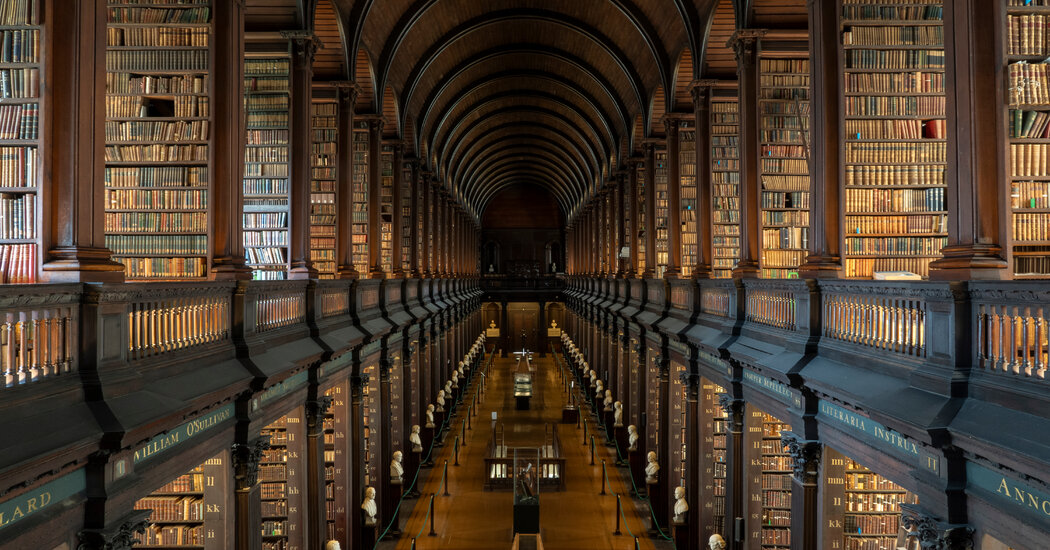

DUBLIN — The Long Room, with its imposing oak ceiling and two levels of bookshelves laden with some of Ireland’s most ancient and valuable volumes, is the oldest part of the library in Trinity College Dublin, in constant use since 1732.

But that remarkable record is about to be disrupted, as engineers, architects and conservation experts embark on a 90 million euro, or $95 million, program to restore and upgrade the college’s Old Library building, of which the Long Room is the main part.

The library, visited by as many as a million people a year, had been needing repairs for years, but the 2019 fire at Notre Dame cathedral in Paris was an urgent reminder that it needed to be protected, according to those involved in the conservation effort.

“We already knew that the Old Library needed work because of problems with the building,” said Prof. Veronica Campbell, who initiated the project. “When we saw Notre Dame burning, we realized, ‘Oh, my God, we need to do something now!’”

Much of the effort will be focused on conserving the historic worked wood that makes up much of the library’s interior and the frames of its windows, as well as improving fireproofing and environmental controls needed to protect the valuable book collection.

Faced with the example of Notre Dame, and the realization that something similar could happen to an Irish national treasure, the government pledged €25 million, with the college and private donors adding €65 million more.

Work started in April, and in October 2023, the Old Library’s doors will close to visitors for at least three years as it moves into full gear.

In the meantime, visitors are still coming in droves to the library, Dublin’s second most popular attraction for overseas tourists (the Guinness brewery is first). Among the treasures on view is the Book of Kells — an exquisitely crafted ninth-century gospel that is the greatest surviving relic of Ireland’s early Christian golden age.

This month, Catalina Gomez, 50, a self-professed bibliophile vacationing from Spain, stood gazing at the Long Room’s barrel-vaulted ceiling, towering 48 feet above her, and the parade of graceful windows, arcades and galleries lined with leather-bound books.

Recent Issues on America’s College Campuses

“As soon as I came in, I was amazed to see a space like this,” said Ms. Gomez, a legal official. “I’ve been to many old libraries around the world, but I’ve never seen anything so spectacular.”

She added, “It’s making me feel very emotional.”

Helen Shenton, Trinity’s library director, likes to highlight the features of the Long Room that can have such an effect on visitors. She stood in the door of the room recently and pointed to the galleries and shelves slanting off into a vanishing point, 213 feet away at the far end. “It’s such a beautiful perspective,” she said. “And it’s Ireland’s front room because every visiting head of state comes here.”

Ms. Shenton said she had twice hosted Joseph R. Biden Jr. at the library, the first time when he was vice president (“he came in 20 big black cars with Secret Service people”) and a second when he was a private citizen again (“he just walked down here by himself”).

Many Irish fans of “Star Wars” also note the strong resemblance between the Long Room and the Jedi Archive, portrayed in CGI in the film “Attack of the Clones,” where a young Obi-Wan Kenobi searched for an elusive planetary system. Lucasfilm, which had not sought any image rights, denied there was any connection.

Ian Lumley, a heritage officer at An Taisce, a nongovernmental organization that promotes the conservation of Ireland’s built culture, said that preservation of the Old Library was critical given its international prominence — and its storied history.

“Back in the 18th century, Trinity was the university of the Irish Enlightenment,” he said, an alma mater to writers and thinkers like Edmund Burke, Oliver Goldsmith and Jonathan Swift.

“Those people would have used that library in the way modern students use the new libraries,” he said. “The atmosphere and books in the Long Room are so special that it’s vital nothing should be lost.”

The conservation effort — informally named “The Great Decant” — started on April 1, when the first tome, Volume 1 of Reeves’s “History of English Law,” printed in London in 1869, was taken from its place on shelf 1.1., in the Long Room’s upper gallery, which is closed to tourists. The book was dusted with a specially modified vacuum cleaner, it was measured, its physical condition was noted, and its details were checked against the Long Room’s catalog, written in 1872.

The book was then labeled with a radio-frequency identification tag and put in a bar-coded box — the first of more than 700,000 books, manuscripts, busts and other artifacts that will be relocated from the Old Library to a climate-controlled, off-campus storage facility.

When the books are all gone, specialists will go to work on the Long Room, upgrading visitor facilities, repairing damage and shoring up defenses against four age-old enemies: time, damp, pollution and, most pressing, fire.

The present fire defenses have relied on hand-held extinguishers.

Ms. Shenton, the library director, said new technologies — possibly involving water-misting systems, rather than sprinklers — would aim to suppress potential fires without doing too much damage to the books. A contractor is being sought to build a “burn room” — an exact model of the Long Room and its contents — to be ignited so specialists can study the best way to hold back the flames.

To slow the inevitable long decay of the books, and to protect them from dust and acidic particles seeping in from city traffic, new microthin clear covers, or “slip cases,” are being designed for each volume.

“We’ll have to remove one book from each shelf to make up for the extra thickness,” said John Gillis, Trinity’s chief book conservator. “Well, that’s what we negotiated with the librarians — one book per shelf. It could end up being two.” He lowered his voice conspiratorially: “I’m a conservator. Librarians are our enemy. We say, ‘Don’t touch that old book!’ and they want to let people open it and read it!”

Two reading rooms, hidden away at either end of the Long Room, will be relocated to the basement of the modern Usher Library nearby, and scholars will still be able summon Long Room books from off-campus storage.

To preserve the tourist experience for as long as possible — a key source of college income — the shelves most visible to visitors will be the last to be cleared. The Book of Kells and other precious artifacts will be temporarily displayed in the college’s 18th-century Printing House until an enhanced exhibition space is ready under the upgraded Long Room.

There, says Ms. Shenton, close attention must be paid to the damp: The eastern half of Trinity’s campus was once a tidal marsh.

“The reason the Long Room was built on the first floor was because we’ve lots of underground streams here, and a high water table,” she said. “When we have to mow the cricket pitch, we can’t do it at high tide because we’re so close to sea level.”

For the next few months, the only glimpse that visitors will have of The Great Decant will be a few shadowy figures high up in the Long Room’s gallery, unshelving, processing and boxing books.

Among the project assistants is Kayleigh Ferguson, 28, from Syracuse, N.Y., a qualified librarian who took the work as a side job while studying for a doctorate in Maynooth University, near Dublin.

Asked if she liked her new work station, high in the picturesque gallery, surrounded by fragrant old books, she laughed.

“I don’t complain,” she said.