MADRID — James Joyce once said that he hoped his groundbreaking and famously challenging novel “Ulysses” would “keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant.”

Since its publication 100 years ago, nearly every line has certainly continued to puzzle his readers. There has also been debate over whether the book could be illustrated, and which artist might take it on. Now, a new edition of “Ulysses” is presenting the work under a fresh light.

Timed to commemorate the centennial of Sylvia Beach’s publication of “Ulysses” in Paris, this new edition contains over 300 images by Eduardo Arroyo, a celebrated Spanish painter and graphic artist who died of cancer in 2018. Fascinated by “Ulysses,” Arroyo said in a 1991 essay that imagining the illustrations kept him alive when he was hospitalized in the late 1980s for peritonitis, an inflammation of the abdominal lining.

This new “Ulysses” edition was published late last month in both Spanish and English, by Galaxia Gutenberg, a Spanish publisher based in Barcelona, and Other Press, an independent publisher in New York. The book’s release — more than three decades after Arroyo produced his images — was long delayed because of copyright disputes.

Arroyo had initially hoped that his drawings, watercolors and collages could be published as a new “Ulysses” in 1991, to mark the 50th anniversary of Joyce’s death. But Joyce’s estate opposed the idea of an illustrated edition. Without that approval, Arroyo initially had to limit himself to printing his images in a book based on Joyce’s work, written by the Spanish author Julían Ríos.

Arroyo was able to reignite his “Ulysses” project only a decade ago, after the novel entered the public domain and Joyce’s heirs could no longer stop him from using the original text. Stephen Joyce, the grandson and last direct descendant of the author, died in 2020.

Joan Tarrida, the publisher of Galaxia Gutenberg, said in an interview that it was unclear exactly why Stephen Joyce had opposed an illustrated edition, given that his grandfather had sought to convince two of the most famous artists of his time to produce artwork for his novel.

Joyce was turned down by Pablo Picasso — probably on the advice of his friend Gertrude Stein, who was no fan of Joyce, according to Tarrida. He did not fare much better with Henri Matisse, who was more interested in illustrating the “Odyssey” and its ancient Greek heroes than “Ulysses,” whose structure mirrors that of Homer’s epic poem.

Still, after an American judge in 1933 removed an import ban on “Ulysses,” which had been censored on grounds of obscenity, Matisse accepted a $5,000 offer from George Macy, an American publisher, to incorporate a few of his “Odyssey” etchings into an illustrated, limited and deluxe edition of “Ulysses.” In 2019, a copy of Macy’s edition was sold at auction by Christie’s for $13,750.

Meanwhile, signed copies of Beach’s 1922 edition of “Ulysses” have been among the most expensive 20th-century first-edition books sold, fetching over $400,000. The new edition retails for $75.

Right up to his death, Arroyo worked on the book’s draft with Tarrida, who had also previously published some of Arroyo’s writings. Other Press joined the project after Judith Gurewich, its publisher, accidentally came across some of Arroyo’s drawings during a visit to Tarrida’s office in 2018.

While waiting for him, “I saw all these exceptional paintings and drawings strewn across the room, and I just fell in love with them,” she said in a phone interview.

After completing his “Ulysses” images, Arroyo wrote an essay in 1991 to explain his fascination with the novel, as well as how difficult he found it to turn Joyce’s words into images, leaving him worried at one point that “Ulysses” would “finish what the peritonitis had not achieved.”

He added: “At various moments I came close to throwing in the towel, to finally free myself forever from such a sizable enterprise.”

Tarrida said that readers could treat Arroyo’s artwork as “a parallel reading” to Joyce’s words. Gurewich said that she would even recommend that first-time “Ulysses” readers admire Arroyo’s vibrant watercolors and evocative drawings and then try to link them to a specific passage in the novel, rather than start by reading the text.

“You can look at an illustration and then find on the page what Arroyo picked to illustrate,” she said. “If you’re intimidated by ‘Ulysses’ — as I am — this is a very fun way to reconstruct the book.”

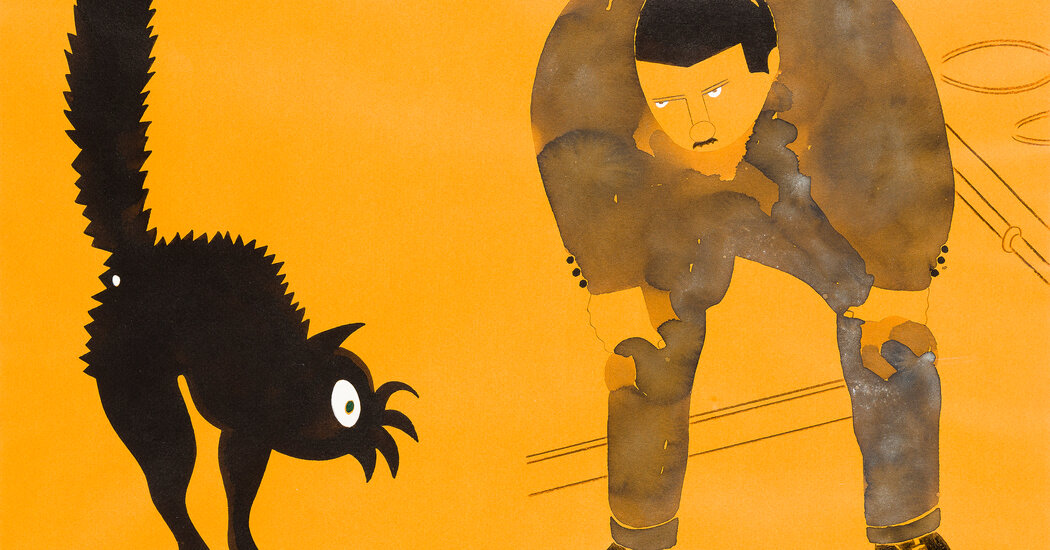

Just as Joyce used an array of styles to write “Ulysses,” Arroyo deployed a range of techniques to represent the author’s characters as they meander through Dublin, from paper collage to ink and watercolor.

Some of Arroyo’s black-and-white illustrations are printed in the margins of the book’s pages, while others are double-page paintings whose vivid colors are reminiscent of the Pop Art that inspired him. He also filled his version of “Ulysses” with eclectic images of shoes and hats, bulls and bats, as well as some sexually explicit representations of scenes that drew the wrath of censors a century ago.

Megan Quigley, an assistant professor of English who teaches in the Irish Studies program at Villanova University, said that she welcomed the release of an illustrated “Ulysses.”

“I tell my students to find anything they can that will help us to understand Joyce’s master novel — literature or music mentioned, historical references, later novelists influenced by Joyce (like Sally Rooney), maps, charts, previous minds who have tussled and argued and written about Joyce in everything from scholarly articles to blogs and fanfic,” she said in an email. “Joyce’s universe is one for the obsessive reader who will find any clues to chart their way through the novel.”

She added: “I’m happy to throw my hat in to support an edition of ‘Ulysses’ with images.”