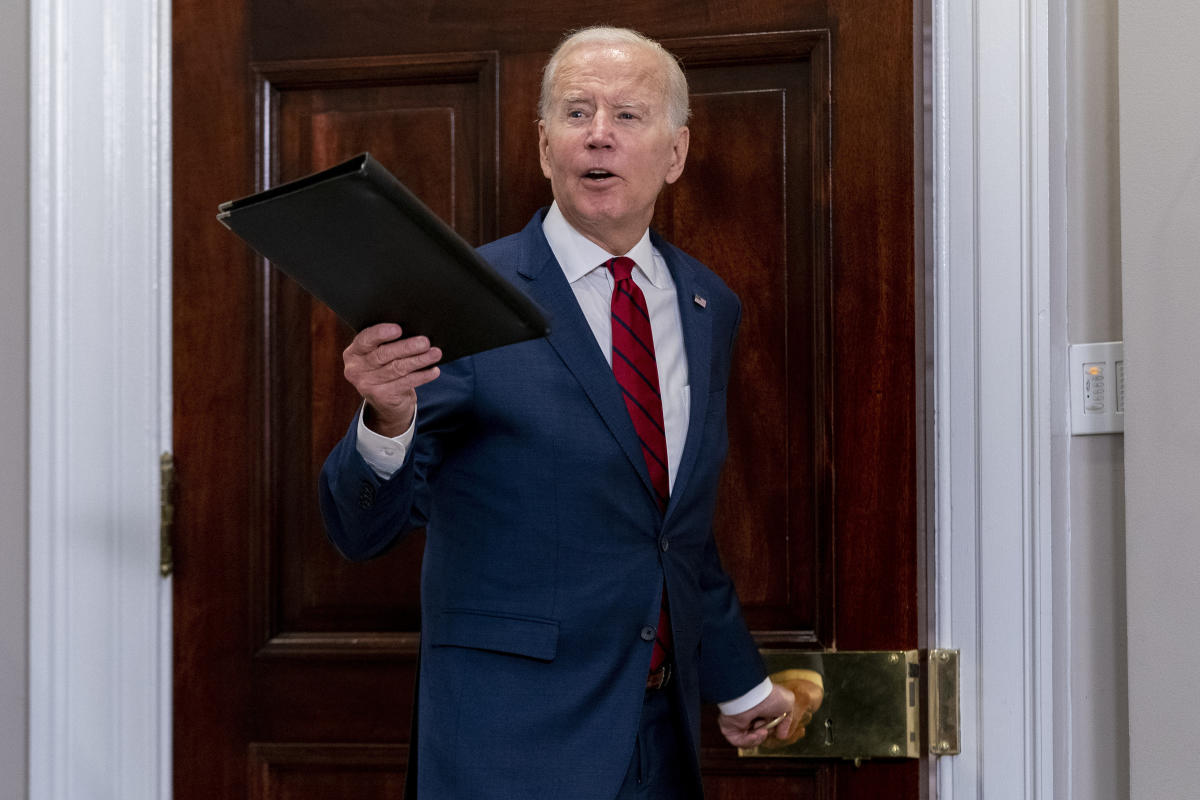

When President Joe Biden speaks Wednesday at the United Nations General Assembly, the two most important people he’ll be addressing won’t be in the audience — Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping.

The Russian autocrat’s invasion of Ukraine is the world’s biggest geopolitical shift over the past year, and it gives Biden plenty of fodder for his address to world leaders, especially on the topic of protecting democracy.

But it is President Xi’s plans for China, his increasingly iron grip on the country, and America’s growing tensions with Beijing that could reshape global rules for generations to come. How Biden tackles China in his speech could matter more than any other element.

All that said, like most presidential speeches at UNGA, Biden’s oration will likely tackle a vast array of topics, and sometimes what’s not mentioned is most interesting of all.

Many U.S. and foreign officials privately despise UNGA, with its constantly shifting schedules, meandering speeches and traffic snarls. This year’s UNGA comes as Britain mourns Queen Elizabeth II, and many world leaders will have rushed to New York from her funeral, adding to the chaos. Still, many officials concede that UNGA is useful to forge new connections, catch up with old ones and even make a backroom deal or two.

As the week proceeds, here are five things to watch:

1) Will more countries step up to rally behind Ukraine?

Ukraine’s recent battlefield victories against Russia have given Kyiv and its Western supporters a psychological boost, and Ukraine hopes that translates into more global support, including more weapons from the United States and its allies.

Biden is sure to praise the existing substantial international support for Ukraine. But it’s worth watching how far Biden will go to urge more support for Ukraine from many of the world’s countries that have remained effectively neutral.

Those countries — many of them in Africa — have generally tried to keep good relations with the Kremlin though without outright supporting its invasion and while calling for diplomacy to end the war. Many such countries also have suffered from rising food and energy costs resulting from the conflict, as sanctions and Russian efforts to block Ukraine grain exports have taken a toll. “Russia has successfully presented a counter-narrative that the sanctions are responsible for the food and fuel inflation,” said W. Gyude Moore, an analyst with the Center for Global Development.

Last week, Biden met with the president of one these countries, South Africa’s Cyril Ramaphosa, but publicly didn’t pressure him on the Ukraine crisis. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has been granted a special allowance to deliver a pre-recorded speech during UNGA. As has become usual, Russian leader Vladimir Putin is not expected to attend, but his foreign minister has been granted a visa.

2) How will the U.S.-China competition play out?

U.S.-China tensions have spiked thanks to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s August visit to Taiwan, and Beijing has curtailed its various dialogues with the United States as a show of anger. That animosity, which has been growing for reasons beyond the Pelosi trip, will loom over UNGA. Biden’s latest seemingly unambiguous promise on CBS News’ “60 Minutes” that U.S. troops would defend Taiwan against Beijing won’t help.

The question is whether U.S. and Chinese officials will use UNGA as a setting to openly call for a reduction of friction or if they will simply hold the line and defend their prerogatives. (It’s doubtful either country will want to raise tensions, but each has a domestic audience to think about, too.)

Biden is likely to try to strike the balance he’s been trying to strike since taking office. He will acknowledge, perhaps even criticize, China’s economic, human rights and other abuses, but he’ll also insist that the two countries must work together on transnational challenges such as climate change. He may do much of this without saying the word “China.”

Biden has long made clear he doesn’t want a war, but that the United States must be ready for intense competition with Beijing. China’s Xi isn’t expected to attend UNGA. But will the senior Chinese delegates representing him stay in the room when Biden speaks?

3) What will Biden say about protecting democracy?

One of Biden’s favorite causes has been promoting, and protecting, democracy in the face of threats such as far-right populism and Beijing’s version of communism. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — a literal war between autocracy and democracy — gives Biden the perfect excuse to harp more on the importance of protecting freedom and liberty.

But Biden hasn’t exactly helped his cause in recent months by hanging out with dictators such as Saudi Arabia’s de facto ruler, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. In fairness, many U.S. presidents have talked big about democracy while keeping close a useful autocrat or two. It’s worth noting, too, that Russia’s invasion of in Ukraine caused the chaos in the energy market that helped convince Biden to engage the Saudi royal and other Arab monarchs.

During UNGA, Biden also is expected to hold several bilateral sessions with world leaders. Which countries will make the cut? And speaking of gatherings and democracy, the Biden administration is expected to host another Summit for Democracy later this year. Can’t wait to see the invitation list for that one.

4) Will Biden make new moves to address mass atrocities?

During his term so far, Biden has recognized several genocides, from what befell Armenians more than a century ago to the more recent tragedy of Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar. Biden has even suggested he believes Putin is carrying out a genocide in Ukraine.

The Biden administration’s willingness to recognize such atrocities is unusual, because past U.S. governments often tried to sidestep such questions due to political and legal sensitivities. The Biden team is cautious, too, but in some cases, it’s tough to avoid the conclusion.

Biden has imposed sanctions and taken other steps, in particular over the Rohingya case, to complement his rhetoric. But human rights analysts will be watching whether Biden raises the issue of mass atrocities in his speech Wednesday or unveils new measures — perhaps offering more support for U.N.-led anti-atrocity efforts — to punish the perpetrators.

Ukrainian and European Union leaders are increasingly calling for Russia to be held to account, such as by an international tribunal, for war crimes in Ukraine. The recent discovery of mass graves in Ukraine’s Izyum area following a Russian retreat could add pressure on Biden to commit more U.S. resources to promoting such accountability.

“He deserves credit for identifying the crime of crimes. Yet, consequences must follow. Otherwise, these statements will have little lasting impact,” said Knox Thames, a former State Department official.

5) Will there be some breakthrough on the Iran nuclear talks?

Among those expected to attend UNGA is Iran’s President Ebrahim Raisi. He’s a hardliner whose government has, often through its own actions, failed to agree to a path to restore the 2015 Iran nuclear agreement. But neither the United States, Iran nor other countries involved are willing to abandon diplomacy, and in the past the United States and Iran have used the sidelines of UNGA for quiet discussions. Or at least they’ve tried.

Raisi is coming to UNGA at an unusually sensitive moment. There are reports that Iran’s 83 year-old supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, has had some recent health problems, although he did make a recent public appearance. Khamenei has the final say on matters of state in Iran and that includes reviving the nuclear deal.

Iran’s Islamist regime also is facing protests from a population angered by the death of a young woman who is alleged to have been beaten by Iranian morality policy. Raisi, meanwhile, is facing withering criticism, including from the Biden administration, for being unwilling to acknowledge that the Holocaust happened in a “60 Minutes” interview.

It’s highly unlikely that Raisi himself would wade in to any nuclear negotiations on the UNGA sidelines. That said, there are other Iranian emissaries who could be tapped for such discussions, which may have to be mediated by Europeans because Tehran has for many months refused direct talks with Washington. European Union leaders, however, are downplaying the chance of any breakthrough.

“The lack of trust is immense and the minimal basis for a constructive U.S.-Iran working relationship has never been established,” said Suzanne DiMaggio, an expert on Iran, North Korea and nuclear issues. “Absent an immediate breakthrough, a time out until after the U.S. midterm elections is likely.