Read also: Moscow is playing PR game over grain exports

But Russian discontent with its share of benefits from the deal – sanctions relief on its fertilizer exports – could put the breakthrough deal at risk.

The United Nations, Turkey, Ukraine, and Russia launched the deal – the Black Sea Grain Initiative – in July. Under it, the parties agreed to unblock the Ukrainian grain trade halted by Russia’s full-scale invasion and war.

At the time, the UN presented the Black Sea agreement as a beacon of hope that could help solve future food crises and ease the growing food prices worldwide.

Ukraine was again able to transport its food exports by sea without putting its ports at risk of Russian attack. Russia, in turn, got guarantees that sanctions imposed on it for its unprovoked invasion of Ukraine would not affect Russian grain and fertilizer shipments.

Read also: Ukraine provides details of “grain agreement” struck in Istanbul

As of Sept. 13, 129 vessels have already left the Ukrainian ports Odesa, Chornomorsk, and Yuzhy, transporting almost 3 million tons of grains and other foodstuffs, the United Nations reports.

UN officials see the first results of the Black Sea Grain Initiative as a success that helped to unblock the important international trade routes. Export food prices have also decreased by at least 1.4 percent, Amir Abdulla, the UN Coordinator for Black Sea Grain Initiative, said at a briefing in UN headquarters on Sept. 13.

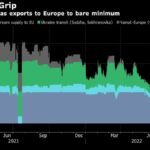

But Russian officials think otherwise, claiming sanctions have stalled Russia’s fertilizer and grain trade. Moreover, Russian President Vladimir Putin on Sept. 6 accused EU countries of diverting Black Sea grain to their own markets and called for limits on the export of Ukrainian grain.

During the Eastern Economic Forum in Russia, Putin said EU nations have taken the bulk of Ukrainian grain exported via the Black Sea. Russian president also claimed he would talk to Turkish President Erdogan about limiting destinations Ukraine can export its grain.

Some 28 percent of Ukrainian grain exports went to low and lower-middle income countries: Egypt (10%), Iran and India (5%), Sudan and Kenya (2%), and Djibouti, Lebanon, Somalia, and Yemen (1%).

Read also: Ukraine sums up work of ‘grain corridor’ so far

Another 27% went to upper-middle income countries: Turkey (19%) and China (8%), while 44% was sent to high-income countries: Spain (13%), The Netherlands (8%), Italy (7%), South Korea (5%), Romania (4%), Germany (2%), and France, Greece, Ireland and Israel (1%).

However, Russian claims that the Europeans are hogging Ukrainian grain at the expense of poorer nations are baseless, as UN explains.

“Some of the cargos going to (European) destinations are then shipped further in the same form or processed as flour,” the UN’s Abdulla said on Sept. 13.

“So the route featured in the shipping data is not always the end destination of the grain.”

Read also: Two Russian sea captains charged with smuggling Ukrainian grain

And while demanding limits on legitimate Ukrainian grain exports, Russia is continuing to sell as its own Ukrainian grains stolen from the occupied territories, using a shady reshipment mechanism, Crimean Tatar journalist Osman Pashayev the told NV.

“They load Ukrainian grain to the cargo vessels in Crimea,” Pashayev said. “Then those ships go to the Russian port Kavkaz. There Russians reload Ukrainian grain to other vessels with no track record of visiting Crimean ports. After that, they successfully sell it – even to Europe.”

Back in May the Ukrainian Agriculture Ministry reported that Russia had stolen more than 500,000 tons of Ukrainian from the occupied territories. Activists have previously spotted vessels with stolen grain in Turkish ports.

Read also: Lebanon releases ship with stolen Ukrainian grain from custody, Kyiv warns Beirut of consequences

However, the UN has no control over Russian grain under the terms of the agreement, Abdula said. The organization monitors only cargos going from three ports located on Ukrainian-controlled territory, and Ukrainian port authorities monitor other exports.

“For what we are monitoring and have oversight of, we can be fairly confident that all parties to the initiative agree on the ownership, control, sale, and movement of the quantities that go through that corridor,” Abdula said.

While Ukraine potentially faces more limitations, the is UN working hard to satisfy all of the Russian demands and lift the remaining restrictions on the fertilizers and grains trade. In particular, the organization is trying to unfreeze sales of Russian ammonia, a key fertilizer component, through Ukrainian territory, Reuters reported on Sept. 13.

“We needed to stabilize the grain and fertilizers markets in the world,” UN Senior trade official Rebeca Grynspan said during a press briefing on Sept. 13.

“The (Black Sea Grain Initiative) agreements were essential to making food affordable for millions of people.”

Read also: First shipment of Ukrainian grain arrives in Africa

Read the original article on The New Voice of Ukraine