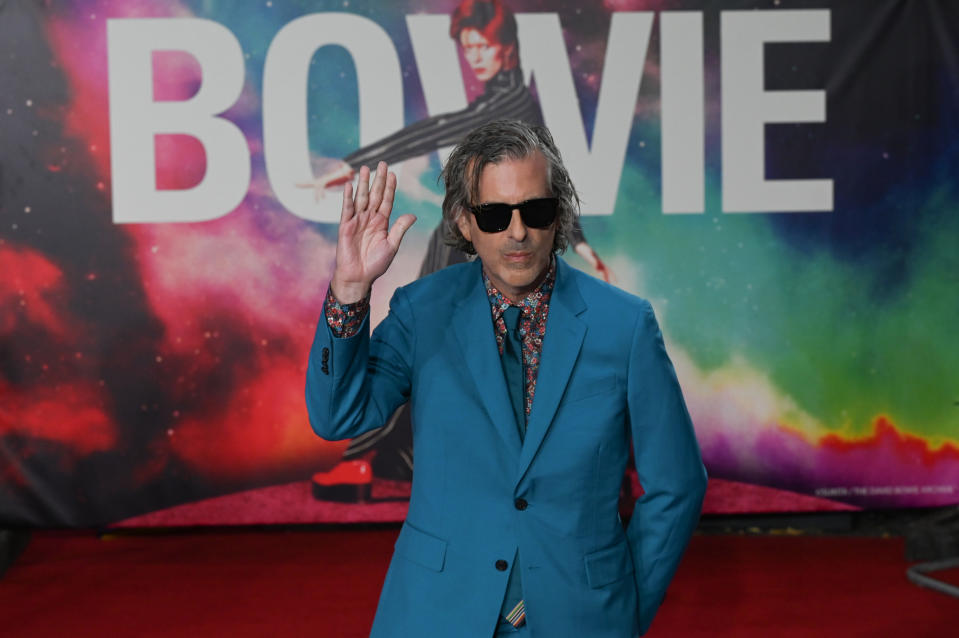

Fifteen years ago, Brett Morgen — director of the barrier-breaking documentaries The Kid Stays in the Picture, Crossfire Hurricane, Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, and now his most ambitious and artistically bold project yet, the David Bowie doc Moonage Daydream — met with Bowie himself “to discuss doing a very different type of film.”

Morgen’s fantastical idea for that alternate-universe scripted movie “was like a hybrid performance piece, essentially imagining if Bowie never evolved after Ziggy and we found him in modern-day Berlin, playing this dive cabaret on Monday night at 3 in the morning to the last few people on Earth who were interested in him. It was this whole piece about not evolving.”

That movie obviously never got made. Bowie had suffered a career-derailing heart attack just three years prior and “was in sort of semi-retirement”; his business manager, Bill Zysblat, later phoned Morgen to say, “David really enjoyed the pitch, but it’s not the right time.” Of course, unlike Morgen’s fictionalized version that never made it to the screen, the actual David Bowie never stopped evolving. The visionary, shape-shifting artist returned to music-making in 2013 after a decade-long hiatus, and released one of his greatest albums, Blackstar, just two days before his death in January 2016.

Zysblat, now the executor of Bowie’s estate, eventually reconvened with Morgen in 2016 and granted the acclaimed director unprecedented access to the artist’s vast archives. “I think Bill understood that I don’t make traditional documentaries,” Morgen tells Yahoo Entertainment. Morgen proceeded to work on Moonage Daydream for five years, two of which consisted solely of “screening six days a week, 10 to 12 hours a day, which was like the greatest job on Earth.” He pored over literally more than five million assets, including unseen paintings, drawings, recordings, photographs, films, journals, and 16mm and 35mm performance clips.

The result is Morgen’s wondrous, kaleidoscopic, IMAX-ready, 140-minute Bowie documentary/art-piece, Moonage Daydream. But while there were times when the project was “a filmmaker’s dream,” there were other instances when it was a nightmare. Ironically, Morgen suffered a heart attack of his own during the arduous process of crafting the film, [on Jan. 5, 2017 — and after that near-death experience, he learned more from Bowie’s life journey than he’d ever expected.

“Not to get heavy, but I just will say, as a preamble, that this is an emotional thing for me to say,” notes Morgen — who, at 53, is now only four years younger than the age Bowie was when Bowie had his heart attack and subsequently retreated into a quieter private life with his wife Iman and daughter Lexi. A self-proclaimed workaholic who sadly recalls getting bittersweet Father’s Day cards that read, “Hey Dad, thanks for the work ethic. You really taught me the value of working hard,” Morgen says: “It’s a little heavy-handed, but very early, when I was about to start listening to [Bowie’s archival] interviews, I had a massive heart attack. I flatlined, and I was in a coma for a week. And it was not an accident, you know. My life had been pedal-to-the-metal, my whole life working nonstop and smoking and not exercising and stressing out over every little detail. And so, I had a heart attack at 47. And when something like that happens, you question things. I have three children, and [the heart attack occurred on] one of those kids’ birthday. The other one’s birthday is actually David’s birthday. I was in coma on her birthday, which was a year to the day David died. And so, you deal with some pretty big questions.

“And as I was coming out of that, there was David,” Morgen marvels. “I did not expect to discover that he would provide a kind of road map to how to lead a more balanced and satisfying and fulfilling life. His lines [in Moonage Daydream] about how you don’t really appreciate life until you’ve lived more days than you have in front of you — these lines were really, really moving. And so, I can’t talk about the messaging of the film without talking about the heart attack, because I don’t think this film would’ve been this film in 2016. I wouldn’t have been receptive. I would not have been open. I wouldn’t have heard it. … The film offered an opportunity for me ponder, should I not be here anymore, where I would direct my children to go to answer any question? What should I do with this situation? ‘Ask David.’ And so, that was the journey.”

Feeling more inspired than ever after immersing himself in thousands of hours of Bowie’s interviews for two years — and yes, still toiling very hard, while now trying to achieve balance in his life — Morgen then started (and restarted, and restarted yet again) the process of shaping Moonage Daydream’s non-linear narrative. It was such a daunting process, it’s a wonder he didn’t go into cardiac arrest a second time.

“I couldn’t figure out the film at all,” Morgen admits. “It took eight months to crack how to structure it, because my goal at first was to have no narrative. But that, obviously, for two hours and 20 minutes, is impossible. So, then it was about creating a narrative that wasn’t entirely chronological or biographically rooted, but still sustained forward momentum. … The film was designed to feel spontaneous. I don’t need another biography piece. My feeling is, if I can get it in a book, then I don’t want to see it on the screen. And so, I think that’s what I tried to do in the film: It’s everything you can’t really explain in a book. It’s almost like a haiku.”

Wanting to “create this IMAX music experience, which was basically like a theme park ride of your favorite artist without any facts,” Morgen decided to not use any talking heads for Moonage Daydream. Instead, he let audio from Bowie’s past interviews — in which Bowie rapturously speaks of the creative process, his unending curiosity, his zest for life, and his love for Iman — serve as the documentary’s sole narration. “Part of the design of the film, part of why it’s helpful not to have people talking about him, is it creates more of that gray space that David refers to, about the sort of mystery of art,” Morgen explains. “And what I like is that his lessons about art are applicable to all facets of life, so whether you’re an artist or a day-laborer, my intent was you would be able to identify, recognize, and gain something.”

Initially Morgen teamed with Oscar-winning film editor Bob Murawski (The Hurt Locker, multiple Sam Raimi movies), whose “fingerprints are still all over the film. We worked together for about five weeks until the pandemic hit and we sort of separated out, but he’s the greatest editor that I’ve had.” The COVID-19 lockdown, along with budget constraints, forced Morgen to finish the editing job on his own (“I was sitting there making a film about alienation and isolation, thinking to myself, ‘Wow, this is really timely’”), but what actually “set the film in motion” was a “44-page manifesto” that Morgen wrote and was “really sheepish about sharing” with Murawski.

“It was just stuff like, ‘If you buried the film in the desert and 10,000 years from now we blow ourselves up and sentient beings later discover this film, would they think it’s a life that was actually lived? Is it a myth? Is it a prophet who came to Earth? Is it one of theirs who was here before them who’s reporting back? No — it’s a transmission that these sentient being are watching from a different planet, sort of like their version of Star Wars,’” Morgen laughs, insisting that his manifesto will never be seen by anyone but Murawski. “There were all wacky, really embarrassing ideas, but I think the film forced me to get to a place of game-playing and role-playing. It’s almost embarrassing to discuss, but it was required to get to here.”

[embedded content]

Morgen continued to write “about chaos and the 20th century and Freud and stuff,” but he understandably struggled to “get all those themes wrapped in.” After eight months, his work space started to feel “like a coffin” — an eerie simile for Morgen to employ, given his health scare just a couple of years earlier. “So, I drove to LAX, jumped on a flight to Albuquerque, went to the train depot, got a ticket on the Amtrak back to L.A., and I said, ‘I’m not going to go home until I crack this.’ And the second the train started moving, it started pouring out. I was trying to fashion David’s story through Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey, with the idea that he was the one creating the storms. He was the one creating the challenges for himself. And in that context, [record producer] Brian [Eno] was Yoda, and he was going come back with the Outside album.”

It all sounds pretty far-out and fantastical… but it all works, especially on the vivid IMAX screen. (Morgen stresses that he can’t imagine any other musical artist’s story being told this way.) And along with the Moonage Daydream filmmaking process giving Morgen new appreciation for the concept of work/life balance, it helped him reassess Bowie’s later-period albums, like the aforementioned 1995 electronic record Outside. In fact, Morgen now cites Bowie’s 2002 album Heathen as his current favorite. A man who frequently, humbly describes himself as “sheepish” or “embarrassed” when discussing Bowie, the director goes back to that fateful 2007 pitch meeting, before he came to appreciate those late-career records.

“This was the not-so-good part of that meeting,” he recalls with a rueful chuckle. “I sat down with David. His office on 57th Street was very small and intimate. It was just David, Bill, [Bowie’s secretary] Coco [Schwab], and myself. I had just put out a film called Chicago 10, and as we sit down, David just launches into… he was very polite as he said it, but he just destroyed the movie! He was like, ‘I don’t care for it at all,’ and just started ripping me. His mannerisms were quite elegant, but he was just shredding me to pieces! … It was a kind of strange thing, and I’ll admit, I got a little sort of like, ‘F***ing what the f***?’ And then Coco said to me, right after David finished ripping me, ‘What’s your favorite Bowie album?’ And I looked at David and I said, ‘Well, to be totally candid, I can’t say I’ve appreciated anything you’ve done since ’83.’ And he locked eyes with me and went, ‘Touché.’

“But here’s what I wanted to say,” Morgen notes. “I stopped listening to Bowie after Let’s Dance. And then I discovered the [later] music, and I fell in love with Outside and Heathen in particular. And that guilt might have pushed me to work years on this film! It’s very difficult, because you can’t go back. I just fell into the trap [of assuming] when he met Iman that he plateaued and he was not creating great music. But that wasn’t the case. It’s just that his investment in it had changed.”

But it was all meant to be. Years later, Zysblat rang up Morgen — “Apparently David really liked that meeting, despite him trashing my film!” — and not only did he enlist Morgen to make the first Bowie film ever authorized by the singer’s estate, but Zysblat gave Morgen final-cut approval for Moonage Daydream. “Bill’s only dictate to me was: ‘David’s not here to authorize or approve this, so it cannot be David Bowie on David Bowie. It has to be Brett Morgen on David Bowie,’” Morgen says.

“And Bill is very happy,” Morgen adds with a small, proud smile. “When he saw the film, he said, ‘You did the impossible.’”

Moonage Daydream will be released to IMAX theaters on Sept. 16, along with a companion soundtrack; a standard theatrical release will follow on Sept. 23.

Read more from Yahoo Entertainment: