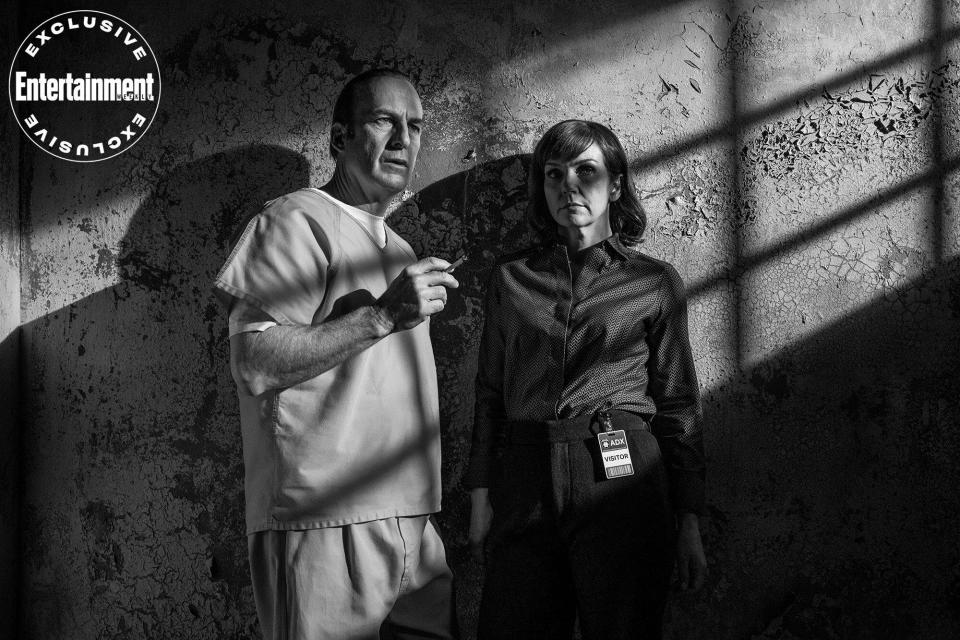

Greg Lewis/AMC Bob Odenkirk as Jimmy and Rhea Seehorn as Kim on ‘Better Call Saul’

On a cool winter morning in the high desert, they have arrived at the end of a road paved with too many bad choices. And one that’s good.

It’s the final day of filming on Better Call Saul, which technically would make this the final day of filming on the entire Breaking Bad saga — a franchise that stretches over 15 years, two series, one movie, and 817 “I’m too old for this s—” disapproving grimaces on a certain fixer’s face. Cast and crew mill about this Albuquerque Studios soundstage, working on the few remaining scenes from the 63rd and last episode of AMC’s acclaimed, unlikely Breaking spin-off prequel. Death has visited this show often in the final season — R.I.P. Nacho (Michael Mando), Howard (Patrick Fabian), Lalo (Tony Dalton), and Swimmy McGill (a goldfish) — and it lingers in the air today. “Say goodbye to the mustache,” announces star Bob Odenkirk, as he lays a key part of Gene to rest on the side of the stage. “Goodbye, mustache,” say a few crew members with a mixture of amusement and dolefulness.

It’s almost time for Odenkirk and Rhea Seehorn to film their very last scene — and puff their last cigarette — as Jimmy McGill and Kim Wexler, two married lawyers joined at the bathroom sink, concocting increasingly elaborate scams. He is the misguided, eager-eyed, corner-cutting attorney who devolves into flashy lowlife whisperer/Walter White consigliere Saul Goodman. She is the savvy, self-sabotaging lawyer who plays her cards close to her ponytail and who brims with great skills and even greater contradictions. Together they became the beating, cheating heart of the show. They were possibility. They were danger. And then they were… done. In one fell swoop, Kim punished herself by quitting the law and Jimmy, the ruinous results of a scheme that had gone so awry that Howard and Lalo became permanent fixtures in the superlab.

Years later, Jimmy was hiding out in Nebraska as neutered Cinnabon manager Gene Takovic, while Kim was living dispassionately in Florida, busying herself with the minutiae of Miracle Whip and flange diameters. When he called her up one day (not just any day; his 50th birthday), she was stunned and quietly told him to turn himself in. He taunted her and told her to turn herself in. She hung up on him. But she did fly to Albuquerque and confess all/most to the authorities and to Howard’s widow, Cheryl (Sandrine Holt).

That phone call jarred something loose in him, too. Jimmy, er, Saul, er, Gene had been dabbling in identity theft and now he was taking bigger risks, begging to be exposed. And he would be exposed, by a nice old lady played by Carol Burnett, sending him on the run, into a dumpster, and into police custody. Which brings us to this minimal-dialogue, maximum-subtext scene, in which he’s wearing his most striking outfit yet: orange ADX Montrose prison scrubs. (You saw it in black and white, but they’re orange in person.) Even more surprising? Kim has shown up as a visitor. In a rotting interview room, the pair lean against the wall and share a cigarette and a silence so familiar, they’re all but back in that HHM parking garage in the very first episode.

Co-creator/showrunner Peter Gould — who wrote and directed the finale — maps out this captivating scene with Seehorn and Odenkirk. (They quickly realize that the prison guard can’t bring Kim into the room because there’s no outside door handle, so one has to be quickly installed.) There’s talk of positioning them against the slash of light streaming across the wall so it mirrors that scene in the pilot. (Cinematographer Marshall Adams has built a digital reproduction of the set to determine the exact angle he wants for that light.) There’s debate over whether Kim should use the term “bar card” or “bar ID” when referring to her New Mexico law license that got her in here. And there’s discussion about how they’ll pass the cigarette between them, a colorful spark (see: the final version of the black and white scene) that has bonded them from go.

Problem is, Seehorn is having a little trouble with the lighter. “You didn’t light that thing very good,” Odenkirk ribs her after a rehearsal. “It’s a s—ty lighter,” she responds. “I had to get the safety down.” Odenkirk and Seehorn will struggle a bit with this herbal prop cigarette, coughing and tearing up. “The amount of smoke they create goes into your eyes immediately like a heat-seeking missile,” Seehorn says.

Weary yet clear-eyed, Gould ruminates on what’s been transpiring on his monitors for this last month, and what will hit TV screens six months from now. “In drama, the perfect elements of an ending are: It’s unpredictable before you see it, and then after you see it, you think there’s no other way it could have gone,” he observes. “The other thing is, in the perfect ending to me, you keep writing the story in your head. There’s still a little bit of a spark left there where you still are thinking about the characters. It’s not all completely tied up. That’s what we’re aiming for. Let’s see if we pull it off.” A shrug. A smile. “It’s going to be very upsetting.”

Upsetting in some ways. Upending in other ways. Uplifting in still others. That’s how Better Call Saul closed the (prison) door after six seasons on Monday night. Titled “Saul Gone,” the transformative series finale saw Odenkirk firing on all cylinders — and through all of his different personas. Facing a life sentence plus 190 years for the felonies that he committed whilst serving as an advisor to meth lord Walter White (Bryan Cranston), Gene summoned Saul Goodman and somehow negotiated a deal with the feds to serve only seven-and-half years in a cush federal prison. He wanted more. But when he dangled information about Howard’s disappearance in exchange for one more perk — mint chocolate chip ice cream, not pre-melted with ants — he learned that Kim had already confessed that particular sin. Something inside him Klicked, and he concocted a plan to get her into that courtroom under the guise that he had turned on her.

Instead, to the feds’ and Kim’s surprise, the shiny-suited, de-mustached Saul grandly owned up to the crimes with Walt. “I was more than a willing participant, I was indispensable,” he said. (Shades of Walt’s “I did it for me. I liked it. I was good at it” admission.) But there was more to confess. Saul suddenly morphed back into Jimmy McGill, but now it was the version that he always wanted to become, the one that Kim was always finger-crossing for. Heeding Ned Beatty’s advice from Network to atone!, he bared his soul to save it, accepting responsibility for his life and his foul-play failings with troubled brother Chuck (“I took away the one thing he lived for, the law”). The cost of his being honest for once, and in court, no less? Just 79 additional years at a much scarier prison. With good behavior, though…

What was Odenkirk’s immediate reaction when he read that final script? “Hooray!” he exclaims. “My first thought was, ‘Hooray, you’ve given him all the feeling and intelligence that he’s had this whole time.’ And he’s embodying who he is — the best part of himself is coming out finally. I’ve always felt he was capable of the choice he makes at the end, to acknowledge his own part in this whole thing. And that he’s not a victim. I love that he does it, and he does it because he loves Kim, and he does it because he knows that in the long run, it’s the thing that’s going to show her that he was always a really good guy. And not a broken snake.”

Gould saw justice being served in that courtroom, poetic, karmic, moral, etc. “It felt right that Saul has been in court so many times as an attorney, and now he’s there as a prisoner,” says Gould. “And it felt right that he’s made a mockery of the justice system, and now he’s part of it. He’s gone from being one of the people in the courtroom who runs the courtroom to being the subject. But he does have agency and he makes this choice when he hears about what Kim has done. I don’t think it’s a choice from the head. I think it’s a choice from the heart: ‘I’m going to be honest for once, even though it’s going to cost me dearly.'”

AMC ‘Better Call Saul’ stars Bob Odenkirk and Rhea Seehorn

Kim — our co-protagonist whose fate was always fretted by fans, given her lack of mention in Breaking Bad — knew that high price. In the finale, she was trying to move out of the self-punishment phase into something more productive, answering phones at a free legal aid-clinic, much like the one she dreamed of starting. And she was heartened to witness Jimmy’s embrace of radical honesty. “I don’t think she saw 86 years coming, but I think she knows, ‘You just closed your jail cell for a long time by doing this,'” says Seehorn. “I think there’s a lot of love and a lot of pain, but also a lot of empathy and compassion for like, ‘I’m glad you made the decision and I’m glad you made it on your own.’ She gives him his own agency, just as much as she insists that people give her hers…. She’s like, ‘If I want my own agency, then he has to find whatever his truth is himself.'”

While Saul neither achieved the explosive exponential ratings growth of Breaking Bad nor topped its own series premiere number of nearly 7 million viewers, this amalgam of cartel intrigue and office noir grew in buzz and critical stature, earning a best drama Emmy nomination every season. And what began as a wild-eyed notion grew into a hotly debated question: Did Better Call Saul manage to become an even greater show than one of the all-time greatest shows — two-time Outstanding Drama Series Emmy winner Breaking Bad? Whatever the case, after a stellar, consequence-administering, tragedy-stained final season that was nearly derailed when Odenkirk suffered a serious heart attack last July (S’all good, he’s fine now), Better Call Saul can be eulogized as one of the supreme TV dramas of the 21st century, right alongside the show that spawned it.

Hard truths were delivered in bulk on these Albuquerque soundstages, the same ones on which Breaking Bad dispensed them by the barrel. The mothership — the Krystal ship — was a wicked-humored drama about a chemistry teacher/latent megalomaniac who cooks up a meth empire with one of his burnout students after receiving a terminal cancer diagnosis. Better Call Saul would also frame a tragic story around transformation, as well as a simple karmic concept that haunted Walt: Chickens always come home to roost. But this sly, ambitious prequel/sequel proved to be its own animal, serving as a meditation on identity, morality, if-only potential, and American hucksterism, as well as the search for and embracing of the self, however treacherous that march toward evolution may be. Plus: elder law!

***

It began as a joke. As a lark. As a wacky what-if. As early as season 2 of Breaking Bad, when Saul and his flimsy Greek columns of justice began stealing scenes, the writers had been cracking wise about a Goodman spin-off. As late as season 5, those writers were hoping they wouldn’t have to kill off Saul, because a spin-off felt really promising. But honestly, this whole thing was also a way for Bad creator Vince Gilligan and fellow executive producer Gould (he who created the Saul Goodman character) to continue the magical experience they’d just wrapped on Bad by spinning an adjacent yarn and working with the same crew. Gilligan tried not to worry himself about the perils of spin-offs, or the imposing shadow of Bad. “I think Peter started to get nervous before I did,” he quips. “I remember it as a time of idyllic blissful ignorance. When you’re not thinking every minute about the pitfalls, you can stumble into great things.”

Gilligan was right, Gould was nervous. “I had two main reactions: One, we’re pushing our luck,” says Gould, who eventually became the sole Saul showrunner. “The success of Breaking Bad was so special, so wonderful, that doing another show in the same universe with the same group seemed too good to be true. So there was a little suspicion. No. 2 was fear: ‘Oh, we’re going to tarnish the legacy of Breaking Bad because this show won’t be as good.’ Of course, the third reaction was excitement.”

Greg Lewis/AMC Peter Gould, Bob Odenkirk, and Vince Gilligan

Their first instincts were to explore a half-hour legal comedy in which Saul would slither his way through a sketchy client of the week. But during the development process, their compass pointed them to a darker place: a one-hour drama about someone in the throes of invention. (Gilligan did have one concern: How do you create a drama around a glib, self-assured character? That required a serious archeological dig into the soul of Saul, né Jimmy McGill.) And how about this for a tantalizing twist: What if the early 2000s-set prequel also came value-added as a sequel, in which viewers could learn what became of Saul after he fled Albuquerque at the end of Breaking Bad?

Odenkirk was sold. Well, at first he passed on the project because he wanted to spend more time in Los Angeles with his teenage son and daughter. But his kids persuaded him to reconsider. And besides, he couldn’t deny “how different it would be from everything I’d done before.” Gould and Gilligan would also address the cartel origin story — and fill in more Breaking blanks — as well as mine a little loquacious vs. laconic dramedy through Jimmy’s run-ins/drive-bys with Jonathan Banks‘ craggy fixer Mike. (Giancarlo Esposito‘s formidable and impenetrable meth lord, Gus, was added in season 3.) To create fresh intrigue, Jimmy was given: a love interest and ally with boundaries in cryptic Kim; adversaries in sanctimonious electromagnetic-allergic brother Chuck (Michael McKean) and Chuck’s stuffed-shirt law-firm partner, Howard (Patrick Fabian); and a client against his will, in the form of cunning, soulful criminal Nacho (Michael Mando). “[The show] is becoming something you haven’t seen,” Odenkirk told EW during a 2015 set visit near the end of season 1. “We don’t know what it is yet. And when we find out what it is, it’ll be neat.”

It was neat. It was off-kilter. It was bifurcated. Armed with a University of American Samoa legal degree, Jimmy — who was never promoted out of the Hamlin-Hamlin-McGill mailroom, thanks to Chuck’s secret dirty work — was shortcutting his way through the legal system from the back of a nail salon while playing out decades-old family dynamics with Chuck. Kim was abetting and discouraging Jimmy’s questionable rackets while deep-diving into interstate banking law. Across town, Mike was meticulously staking out dicey locations while Los Pollos Hermanos owner Gus was fomenting plans for a superlab to subvert his Mexican drug overlords. To recap: On one side of the show, the biggest danger was death by cartel. On the other, it was being stuck in doc review.

The Better Call Saul universe was dense, mercurial, and zany — not as urgent as Bad, more idiosyncratic, stretching out in its own zip code in the ABQ. In addition to brooding character studies, this six-season sidewinder involved a string of menacing Salamancas, a ragtag student video crew from the University of New Mexico, sex toilets, secessionists, mall-walking freeze-outs by Sandpiper seniors, chair yoga, Kennedy half-dollar scams, compromised bingo games, the terms “squat cobbler” and “Chicago sunroof,” homages to Lawrence of Arabia and Planet of the Apes, transposed addresses, swapped pills, swiped Hummels, and transfixing cinematography (behold Jimmy looking around a mirrored corner, creating a warped, recomposed image of a man in conflict with himself).

Greg Lewis/AMC Jonathan Banks as Mike Ehrmantraut and Bob Odenkirk as Saul Goodman on ‘Better Call Saul’

And when it came to exploiting intrigue in its foreboding sunbaked environs and fleshing out these knotty-naughty characters, Saul took its sweet-ass time. In extended sequences worthy of Popular Mechanics deconstruction, Mike would systematically take apart a mysterious device or construct one. To some frustration, Chuck clung to mylar for the bulk of three seasons. The show loved to test and trust the audience, to nestle into the nooks of nuance, to luxuriate in unexpected moments (see: Gus’ leisurely conversation with a sommelier), and have its characters explore and make startling — yet not sensational — moves. “Nothing is as important as understanding the character’s mindset,” says Gould. “Usually when we get stuck, it’s because there’s something about his or her consciousness that we’re taking for granted that needs to be examined.” Seehorn puts it this way: “Peter likes ‘kicking the tires.’ If a character does something that makes it too easy for you to wrap the scene up the way you want to, then he’ll say, ‘We gotta kick the tires. Is that really what the character would do? Is it the deepest thought that person might have?'”

Audiences rolled with it as Jimmy transmogrified from an anything-to-make-a-buck lawyer into something more heartbreaking, soul-rotted, and nihilistic. He was out to prove his brother wrong/right that Jimmy McGill with a law degree was a chimp with a machine gun. And along the way, Odenkirk — revered in the sketch comedy world for Mr. Show — staked his claim as one of the most formidable actors on TV now, deftly sliding between comedy and drama. (In any given episode of Saul. But also in his career.) He was as enthralling to watch opposite Seehorn or McKean as he was a payphone, and he’s been rewarded with five Emmy acting nominations for the role thus far.

While he had 43 episodes of Breaking Bad under his belt (as well as the 2013 drama Nebraska), Odenkirk felt out of his dramatic depth when Saul started up. He invited his costars to his house for rehearsals. He believes that stress caused him to lose his voice a few days before the first day of shooting. Today, at the other end of this journey, “I’m proud that I was able to do [this role], when it demanded it at the highest level,” he says. “And that was because I was scared of letting everyone down.”

McKean praises Odenkirk’s “brilliant mind” and “purity of action,” while Seehorn testifies that he “is a genius, but he’s not accidentally a genius. I think that takes away from the amount of work he’s doing. Incredible attention to detail. He is tireless in pursuit of the best way to do a scene. And he will take big swings and big risks. He allows himself to be changed by the other person’s performance, which not all actors do.”

Gould also lauds Odenkirk’s versatility and accountability. “He’s fun to watch, and he can make lightning transitions like nobody else,” says the showrunner. “But even through all the years on Breaking Bad, what I didn’t fully understand was Bob’s amazing powers of focus, and how hard the man is willing and able to work. He took on the challenge from day one in such a serious, focused way. What we realized was that we could write anything — anything — for him, and he would run with it. And that gave us tremendous freedom to explore the character and to take Jimmy McGill and Saul Goodman to extremes that I don’t think we would’ve ever even thought of if Bob hadn’t risen to the challenge.”

The same could be said of Odenkirk’s most frequent scene partner. As Jimmy’s scams got bigger and his moral fissures deeper, another transformation was transpiring on the show. With her elliptical reactions and disorienting decisions (rewatch season 5’s marriage proposal to Jimmy), Seehorn’s Kim became every bit of a draw as Jimmy — and an utterly mesmerizing character study. And this summer, after several years of being surprisingly snubbed on Emmy nomination morning, Seehorn (whose credits include Whitney and Franklin & Bash) finally scored a Supporting Actress nod for Saul, much to the elation of fans who said they’d riot if she didn’t. (They also said they’d riot if she didn’t make it out of this series alive. Kind of an unruly bunch.)

“The degree of control that you see her exhibiting as Kim is so not Rhea,” marvels Odenkirk. “She’s effusive and fun and just emotionally giving, and Kim is withholding and buttoned down in a way that is the opposite of Rhea Seehorn. Seeing Rhea Seehorn play Kim Wexler is quite an achievement.” If Seehorn’s enigmatic expressions as Kim were art, decoding her face became a science. “The most interesting moments in life are when people don’t talk,” Gilligan says, summing up the show’s ethos.

“It was really a situation of me building this incredible relationship with the writers, as one of the characters who is not verbose, playing against the lead of the show who is insanely verbose,” explains Seehorn. “I kept trusting that they understood what I was doing with my work and in turn they would give me more scenes. Some of the writers even told me they would sometimes take lines out as a show of respect — which sounds the opposite of what it actually was, but they were like, ‘We don’t need to explain that. She’s going to play it.'”

Michele K. Short/AMC/Sony Pictures Television Rhea Seehorn as Kim Wexler and Bob Odenkirk as Jimmy McGill on season 3 of ‘Better Call Saul’

“There’s a paradox at the heart of her performance,” observes Gould. “Rhea made choices in scenes where she had very little dialogue that are amazing, and you just want to watch her. She has a poker face. And yet somehow at the same time, you can read every emotional beat. I don’t know how she does it. If you watch that scene in [the penultimate episode, ‘Waterworks’] where she breaks down on the airport bus together with the scene with Cheryl, she’s so restrained with Cheryl. You can see that it’s costing her. And then when she cries, it’s not just a sudden breakdown, there are a million little colors and transitions. It’s like a painting.”

For a show that thrived on finding itself along the way, Kim was its finest discovery. Gilligan has famously shared that he was initially planning to kill off Jesse (Aaron Paul) on Breaking Bad before recognizing the magnet-ic chemistry between Jesse and Walt. At the beginning of Saul, the writers weren’t sure how critical Kim would be to this long con, especially as they were drilling down on the Jimmy-Chuck unraveling. Soon, though, they began to see something special percolating in Kim and Jimmy — and in Seehorn’s exquisitely modulated performance as someone who was, for better and worse, her own imperfect creation, with full agency. (“You don’t save me,” she would scold Jimmy at one point, “I save me.”) “We all loved Rhea from the get-go,” says Gilligan. “She’s just a breath of fresh air. But it took probably the better part of that first season to realize, ‘Man, we really have a two-hander here.'”

The lightbulb truly illuminated in the writers’ room after Jimmy blew off the job introduction that Kim had set up for him at the end of season 1. “It was really the beginning of season 2, where he says to her, ‘If I take this job, is this’ — and he moves his hand back and forth, meaning the two of them — ‘is this going to happen?'” says Gould. “Just that piece of dialogue told us so much about them, so much about his longing for her, and her doubts about him, and so many other things, that suddenly she became very, very important.”

Odenkirk says that the chemistry was not earned; it was just there in the audition room. “We have a great friendship and an amazing partnership that, like a lot of great ones, just came off the first moment we met,” he testifies. “There was no big learning curve. It was a trust that you just look at the other person and you both know where you’re living in the scene and where the two characters are. You share that world. And that was right off the audition readings that we did together. Rhea came in on a day when there were three women reading, and the other two were great actresses as well, but there wasn’t the [snaps fingers] connection and ease.”

The bond only deepened in season 4, when Seehorn moved into the Albuquerque house where Odenkirk and Fabian lived, where rehearsals and scene analysis often took place. And while Seehorn and Odenkirk love to fastidiously prepare, they live to be surprised by the other. “We both respect each other’s work so much that I’m not only not going to block what he throws at me, I can’t wait to be thrown a curveball,” explains Seehorn of their process. “When people talk about chemistry, if somebody honestly does not know how they’re going to do their next line till the opposing line is thrown at them, that’s the tightwire you’re seeing.”

The onscreen high-wire act that was Jimmy and Kim was predestined to snap, based on his future in Breaking Bad. The daughter of a con artist was both attracted and repelled by Jimmy’s slippery legal ways and alter ego (which, in one of her many contradictory behaviors, she would help to construct). Was Jimmy corrupting Kim? Was Kim influencing Jimmy? Or was there just a dangerous alchemy that flared when the two shared a conversation and a corkboard? Yes. And when their wholly unnecessary plot to take Howard down “a peg” spun out of control, Kim needed to make herself the next casualty. The wildly talented lawyer stripped herself of everything but guilt, a fate that the show’s writers positioned as perhaps worse than death. (Attention, fans who worried that she’d be killed off: “First of all, it never seemed dramatically necessary or logical,” says Gould. “But the other thing is, it’s one thing to die, and it’s another to live with what you’ve done.”)

“It makes it an even bigger tragedy that we are aware of what Kim was capable of — and what she could have done with her life,” says Seehorn. “She is sullied beyond repair at this point. She thinks she has absolutely no right to take on this noble profession that she really put on a pedestal and kind of has been slowly corrupting the whole time…. I got to experience this very organic evolution that [the writers] did, where you just took tiny steps in the wrong direction over and over and over until you realize you’ve dug a hole and you don’t even know how you got there. And I think that’s where she is in that moment. There’s just no light anymore.”

It also sent a devastated, shame-soaked Jimmy into full denial and darkness. “Kim was the last person connecting Jimmy to some hope — a legitimate, straightforward connection that’s balanced to the world, to life, to other people,” observes Odenkirk. “And once she says, ‘Goodbye, I don’t want any more of this and this isn’t good for us, and I’m going to make a choice for us both,’ then he’s like, ‘F— this world.’ And then he’s Saul.”

Just a few episodes from the End, that split was deeply mourned by more than just the audience. “As big as it feels, that’s how big it was for us, too,” says Odenkirk. “It feels very real. It felt like a real breakup.” But heartache now yields to nostalgia, as well as pride in one of TV’s most intriguing, improbable couples, whose first utterance of “I love you” came in their breakup scene. “I loved their shared wry sense of humor, but I loved even more that they had — what’s the right word? — emotional intelligence about each other,” says Seehorn. “I know they both made some very immature decisions outside of it [laughs], but they allowed the characters to be in tune with each other and we were allowed to be perceptive. There’s so many scenes you see with relationships that supposedly people know each other really well, and the whole audience is like, ‘Dude, she’s clearly lying to your face! There’s no way you wouldn’t know that!’ We got to be completely honest in those moments. And [the writers] never sullied them by having them be stupid the next second about what the other one was feeling. I thought it was a huge part of why they looked like a real relationship and why people thought they really had each other’s backs, because they did know each other. They knew each other deeply.”

Greg Lewis/AMC Rhea Seehorn as Kim Wexler on ‘Better Call Saul’

That is fully realized in one of the very last moments in the series, when they reunite in the interrogation room. “I loved that Kim understood, without saying so, why Jimmy made that choice,” says Odenkirk. “There was something about the two of them being at peace — even though they won’t be able to be together now — in that they both fully accept who they are, and the love that they had for each other, and the way it went wrong. It was a beautiful scene to get to play. I think we’ve always struggled with the two characters not being able to see their own shortcomings. And this was a moment where they could look at each other, having fully accepted who they each are, and kind of comfort each other with that — that they both made mistakes and that the feelings that they had were true for each other.”

Seehorn was trying her darndest to tune out the magnitude of the moment — their final scene together! the final scene that the show will film! — but also commune with some of that energy. “I knew I’d have a lump in my throat as soon as I walked onto that soundstage for the last time,” she says. “And I seldom stay in character between takes. But in this instance I did, because I knew that trying to suppress getting too emotional was absolutely appropriate for the scene. Absolutely appropriate. She can’t let Jimmy see how scared and worried she is…. I was very affected by this dynamic, where it felt like Jimmy was trying to make sure Kim was okay, with how worried she is for him, how scared she is for him, how sad she is for him, how hard it is to see him there, how hard it is to leave him there. Even with him helping her light the cigarette, he’s trying to tell her that he’s okay now. And I found that just so touching.”

***

Better Call Saul may have turned into a two-hander, but there were plenty of other limbs that kept the show ambulating in unpredictable, thrilling ways. Along Jimmy’s serpentine path of transformation, the show also spun a morality tale around Bad‘s masterful fixer, Mike. (Especially once he got out of that damn parking kiosk. Not that Jonathan Banks minded his station: “The kiosk was under a bridge or a viaduct,” deadpans the actor. “So that meant that when it was 100 degrees in the summertime, it was shaded. What’s not to like?”)

“You’re now a criminal,” Mike told Daniel (Mark Proksch), who was joining the illicit pharmaceutical game but didn’t view himself a bad guy. “Good one, bad one? That’s up to you.” But even this grumpy ol’ wise man wrestled with his own code.”There’s a side of Mike that is so thoroughly decent and he knows when he is doing wrong,” says Banks. “He knows.” The prequel examined the ex-police officer who was choked with guilt over turning his cop son dirty and inadvertently getting him killed (“I broke my boy”), and who rationalized taking blood money from Gus to fund a better life for his son’s family. This exploration of the franchise’s most stone-cold enforcer was laced with quieter insights, too, such as when he reads The Little Prince to his granddaughter. “I’m so thankful for a scene like that,” says Banks. “Because there are many different levels. It’s not just reading The Little Prince to Kaylee. Mike gets to be… safe. There’s a part of Mike that he can be as tough as you want, but he lives in fear as well.”

Nicole Wilder/AMC Michael Mando as Nacho Varga on ‘Better Call Saul’

Speaking of code-carrying criminals, Saul unspooled the doomed saga of Michael Mando’s Nacho, who was trapped in a no-win cartel game involving sworn enemies Gus and Hector Salamanca (Mark Margolis). Nacho was deeply concerned with protecting those who’d steered clear of a bad choice road (especially his father). He’d make the ultimate sacrifice to ensure his dad’s safety — in the form of a bullet to his own head — but not before taking a principled final stand while kissing off Hector & Co. “The soliloquy is the accumulation of everything he’s learned, everything he’s experienced, and everything he’s become,” sums up Mando. “And to see this character cross over into death on his own terms, without an iota of fear in his heart, and being full-heartedly invested in the love of his father, is just transcendent. It’s like watching a caterpillar become a butterfly. And realizing that this guy became everything he wanted to be in that moment. I mean, he puts the fear of God in all these guys and they’re just left stunned. Because they’ve seen what true power is, and power is not intimidation. They see the power of his love and they have no words.”

One of those men — a man of very few words — was Gus Fring. Giancarlo Esposito was initially reluctant to sign on to Saul; he’d expressed interest in a Rise of Gus prequel and didn’t quite understand how Gus would fit into a Jimmy-focused series with a slightly lighter tone. But in filling out Bad‘s most scrupulous, inscrutable villain, Esposito found purpose in playing a Gus in distress, triggered by the new Salamanca in town. “[The writers] were able to see the crack in my veneer, in terms of how I controlled the chaos and led my organization, and were able to write to a certain vulnerability or fear of Lalo Salamanca,” explains the actor. “Then I was able to be more vulnerable, and a little more frustrated in my performance that Lalo was a worthy opponent and I couldn’t figure out where he was, how to get him, how to be ahead of him. And that kernel allowed me to explore a different part of Gus Fring than I had ever explored before.”

Greg Lewis/AMC/Sony Pictures Television Giancarlo Esposito as Gus Fring on ‘Better Call Saul’

That was on display in season 6’s “Fun and Games.” After the pathologically insular Gus ventured out to a restaurant to celebrate the vanquishing of Lalo, he vibed with David the sommelier (Reed Diamond). If this was indeed confirmation of Gus’ sexuality (see: his ambiguous-if-likely romantic relationship with former business partner, James Martinez’s Max) that was beside the point to Esposito. “I thought it was brilliant, the idea that there’s a vulnerability of a man who’s coming out of the cave and hasn’t really been seen in public in a relaxed fashion in months and months,” he says. “I wanted to dig deeper to find the connection. Whether that be a connection that was inclusive of a titillation that could possibly be a relationship — it was really the basic human connection. And that was a wonderful thing for me to be able to dance in that rhythm, in that music, to see him come alive again to a world that we’ve never seen him come alive in at all… That was just really exciting — and may have been the transformative moment of my time in Better Call Saul.”

Alas, the awakening was short-lived. Gus’ demeanor suddenly darkened and he quickly exited the restaurant, as if he just remembered that he can never put his guard down in this cartel war, and/or he still must avenge Max’s murder at the hands of Hector. Esposito offers an additional read: “That switch for me is that ‘I’ve never revealed myself, even to myself. It would be irreversible if I were able to, so why now?'”

A man desperate to reverse his condition was Jimmy’s brother. A gifted, prideful attorney, Chuck was plagued by electromagnetic sensitivity (supposedly) and sibling envy (definitely). “Chuck is a very self-focused man,” Michael McKean observes. “And you can dig as deep as you want into the obvious jealousies and competition for mother’s love as well as for his ex-wife’s love. The worst thing in his life you can imagine is something he doesn’t understand. A man with a really, really great intellect will be very frustrated if there are things he can’t do — communicate with Jimmy was one of them, and finding the way out of his perceived illness, whatever level that was imagined and what level it was physical.”

Long after Chuck yielded to his demons and killed himself in an altered state, Jimmy was haunted by his older brother’s brutal advice to accept his darker self. (“You can’t help it, so stop apologizing and embrace it. In the end, you’re going to hurt everyone around you.”) Chuck did speak some uncomfortable truths, though filtered through a warped perspective. “He was right about a lot of things, but you don’t go around planting dynamite under the people you’re trying to help, and that’s what happened,” says McKean. “There was a time in his quiet moments when Chuck thought, ‘Well, if he can break all the rules and screw with people, maybe that’s how I’ll get to him. Maybe I’ll find a way to make him destroy himself.’ Even after that big explosion in the first season, there were still times when you felt that they could, at some point or another, put their heads together and come up with a much better human being than either one of them is.”

Michele K.Short/AMC Michael McKean as Chuck McGill and Bob Odenkirk as Jimmy McGill on ‘Better Call Saul’

Like Jimmy, Patrick Fabian’s Howard did wound Chuck, devastating the partner he once revered by offering to buy him out of the firm with his own money. And like Chuck, Howard did clash with Jimmy before winding up in the grave, too. The smug, smiley suit who proudly flew the corporate flag proved to be rather misunderstood, and on his path to self-actualization, he wound up being one of the show’s unexpected moral centers. “The writers opened a window every season to more of Howard,” says Fabian. “We found out that Chuck was more manipulative than we expected. We found that Howard paid for school for Kim, Howard wanted to go out on his own — all those things they dropped in helped us go, ‘Well, maybe he’s not so bad.’ He takes responsibility for Chuck’s death and goes to therapy, embraces it, and he comes out the other side a better, more introspective man. Of course, he is the guy that puts ‘NAMASTE’ on his Jaguar [license plate], so there’s not 100-percent growth, but it’s something.”

Howard was perceptive enough to figure out that Jimmy and Kim were trying to frame him as an addict, and he delivered a sobering scolding (“You’re like Leopold and Loeb, two sociopaths”). Unfortunately it came at the exact wrong time. “He is the only character in the entire series — because of his knowledge of Chuck, because of all these things that they’ve had between one another — who actually can put it together,” says Fabian. “For him to come and nail them to the wall also answers questions for the audience. Howard uncomfortably tells them who they are, what they really look like. And the audience is uncomfortable about that because, let’s face it, they’re rooting for Jimmy and Kim to get together, move to Santa Fe, and have three kids — even though they know that’s not going to happen. When Howard gets to unload, you’re like, ‘Wow, they really did Howard dirty,’ and then the candle blows again. Enter Lalo.”

Greg Lewis/AMC Patrick Fabian as Howard Hamlin on ‘Better Call Saul’

Ah, yes, Lalo. Like Nacho, Lalo was just a name mentioned in a throwaway line in the season 2 episode of Breaking Bad titled “Better Call Saul,” when Saul fearfully asks the masked Walt and Jesse if Lalo sent them to kill him. When starting work on Saul, the producers thought about introducing Lalo in season 1, but Gilligan felt that his appearance could wait. Odenkirk remained curious and relentless, though. “Bob kept saying to me, ‘When are we gonna find out about Lalo? When are we gonna find out about Lalo?,’ recalls Gould. “And I said, ‘Maybe we will, maybe we won’t. We don’t have to address everything.’ And he would shake his head: ‘I think we want to know.'” Once Nacho helped to send Tuco (Raymond Cruz) to jail and Hector into a nursing home after provoking his stroke, “We thought, ‘Instead of going out of the frying pan onto the cutting board, it’s better to go out of the frying pan into the fire,'” says Gould. “So how do we make things worse? And it was: ‘What if Lalo shows up? Let’s see a different kind of cat, let’s see a different kind of cartel capo.'”

Tony Dalton’s chipper outlaw arrived audaciously in season 4, excitedly handing Nacho a delicious plate of food he just cooked up while foreshadowing his death. (“Wait, wait… you’re going to die.”) And he made up for lost time with a grin so frightening that the Joker would run for cover. While Lalo possessed exemplary deduction skills and extraordinary jumping abilities (on only one hour of sleep each night!), he was one-upped by Gus in the superlab, laughing up blood in his final gasp. It was a fitting end to a bad guy that owes a debt to, well, Samuel L. Jackson. “All the other [villains] in the series were all so serious and stoic,” says Dalton. “They were just so bad. And I figured, ‘What happens if we flip this around? What if you see a charming guy that you like?’ And I thought of Pulp Fiction, watched it, and I said, ‘That’s it! Yeah, that’s the kind of guy!’ [Jackson’s Jules Winnfield] says, ‘Say “what” again, motherf—er, I dare you!’ with a smile, and it’s like, ‘Oh, yeah! That could be something that Lalo would be saying: “Well, wait, tell me again, what do you mean? Tell. Me. Again.”‘ And it’s like, ‘Oh s—, this guy’s actually serious, but I just kind of like him, you know?'”

Greg Lewis/AMC/Sony Pictures Television Tony Dalton as Lalo Salamanca on ‘Better Call Saul’

Saul’s mention of Lalo on Bad would be a re-entry point for Walt and Jesse, something fans had been itching for since, well, season 1, episode 1. Better Call Saul interfaced in intriguing or delightful ways with its parent show, slipping Bad characters in and out of the series (from Tuco in the pilot to Betsy Brandt‘s Marie in the finale), and providing a few peeks at Saul in the Bad era. But the show’s third-to-last episode, “Breaking Bad,” revisited that night in the desert ditch and recontextualized the encounter: Saul saw Walt as his jackpot, a chance to mold this inexperienced meth man and show everyone that he could be someone. “What’s the point of bringing up Breaking Bad if we are not doing something different with it?” asks Gould. “By the time we finished 62 episodes with Walt and 62 episodes and a movie [El Camino] with Jesse, we learned what we needed to know about those guys. So what’s left? But the other part of it is these two are really important in Saul’s journey. We thought about the mistakes that Jimmy has made in Better Call Saul, especially the ones revolving around his involvement in Lalo’s business. And then we thought, ‘After all that, how on earth did he end up going into business with Walt and Jesse?’ And the answer became that this is a guy who finds it very hard to resist some of his worst impulses. It’s an escalation of something that Saul has already done.” A pause. “And then, of course, there’s the other side of it too, which is me feeling mildly competitive with Breaking Bad, and saying, ‘Well, okay, Breaking Bad did 62 episodes, we’re gonna do 63!'”

Murders. Suicides. Deaths of the soul. Walt and Jesse’s return. The final season was momentous, adventurous, and treacherous. But one day last summer on the set of Better Call Saul, death and danger suddenly felt a little too real.

***

Bob Odenkirk will tell you many times that he’s lucky to be here. He was a comedy hero before Breaking Bad came calling in 2009 with the cartoonish role of Saul Goodman — and six years later, he got to flesh the hell out of that guy and anchor his own series.

Bob Odenkirk will tell you he’s also lucky to be here in the greater sense. During a break while filming Lalo’s chilling drop-by at Jimmy and Kim’s apartment in season 6’s “Point and Shoot,” Odenkirk was on his exercise bike, hanging out with Seehorn and Fabian nearby on their laptops. He collapsed suddenly and his traumatized friends shouted for help as the life drained out of him. If he had been in his trailer, he’d be dead. If health safety supervisor Rosa Estrada and assistant director Angie Meyer hadn’t been nearby to administer CPR, and if Estrada didn’t just happen to have an automated defibrillator in her car because she was returning it to someone, he’d be dead. If his heart had stayed dormant for any more than the 18 minutes that it did, he’d… well, you know.

“We watched him collapse, we watched him turn blue, we watched him go away and we watched him come back, all in a span of about 25 minutes,” recalls Fabian. “And as the ambulance pulled away with Bob, all I could think of is how thin the notion of making a TV show seemed, and how grateful I was that in between scenes, instead of going to our trailers, we hang out with one another. I like to think of the love, of the friendship that bound us together as work buddies, set the table for the success that was Rosa bringing him back to life and the doctor fixing up his heart. By the time we were back on set, the absurdity of it all just came home to roost. We’re like, ‘Wait a second. Weren’t you dead on this very spot, like, six weeks ago?’ So there we are on set, in the same scene — actually, I’m the one who’s dead at that point. I’m walking around with my head blown off and there’s blood on me and I’m lying on the floor. And we just sort of giggled a little bit. We’re like, ‘What an incredible gift. We all get to see this thing go to the finish line, which is a miracle.'”

“The heart attack and the effects and the resonance of it, I’m going to be thinking about that for a long, long time,” Odenkirk says thoughtfully. “It was kind of a blank space for me. I have no memory of the thing, or the week in the hospital. Zero. It’s hard to conceive, but more impacted were Rhea and Patrick and Vince. I mean, they were standing there, watching me die — and fast. I was dying fast. Thank God for Rosa and Angie, because the CPR means I have a brain that I can work with. But keeping that oxygen going in my brain for the 25 minutes it took before the ambulance was able to get out here made me, you know, survive this thing.”

The other thing that is difficult — “inexplicable” even — for him to process is the gush of goodwill that came from fans. “I’m still absorbing it and thinking about it and thankful for it, and I guess I will be for the rest of my life,” he says. “I just didn’t see myself as somebody who impacted people. I think of people like Tom Hanks, Nick Offerman. These are people that are lovable. I think I’m a little bit more of a prickly character, you know? But people have somehow decided I’m a good guy. And I only can say thank you for being so generous toward me, because I try to be a decent person and kind to people all day, but I get cranky.”

While Odenkirk returned to filming just five weeks after the heart attack, it did take a while for him to feel that he was operating at 100 percent. His working hours were adjusted accordingly. “I would get tired after about eight hours and when they said ‘Cut!’ I would sit down in that set,” he recalls. “Really, I didn’t have the energy for a full day. The producers adjusted things for me, but slowly I gained my energy back.”

He’d need it. There was a lot to accomplish in those final hours. Especially in the final one.

***

“This episode is just like the first season — it’s wall-to-wall Bob,” Gould marvels as the cameras prepare to roll on Odenkirk’s second-to-last scene of the day, of the episode, of the series. “Three different flavors of this character in one episode. Wait, four!”

Right now, he is Gene, about to morph into Saul. And it is literally wall-to-wall Bob: Gene is locked in a holding cell after being apprehended in a dumpster. (Nope, not Jimmy’s first time in a dumpster.) Odenkirk and Gould are discussing how to calibrate the intensity of his pleas to make a phone call.

“Excuse me, another phone call,” says Odenkirk as Gene, knocking on the cell door. The actor turns to the co-creator. “‘Excuse me’ is good. What do you think, Peter? A little softer?”

“Your logic is right, take it down even further,” says Gould.

Greg Lewis/AMC Gene (Bob Odenkirk) finds himself behind bars on ‘Better Call Saul’

Soon “excuse me” turns into shouts of “Hey! I need another phone call! I need another phone call!” Now Odenkirk is whaling the hell out of the door. “This is how they get you? Jesus, what were you thinking?” He punches the door, cries out in pain, slumps to the floor, and then… starts laughing in sheer frustration. (Fun fact: Steps from where Gene is having this laughing freakout, Walt had a similar breakdown on Breaking Bad after he realized that the money in the crawl space was gone.)

When a frustrated Gene notices some graffiti on the cell wall (“My lawyer will ream ur ass”), it sparks an epiphany: Wait a second, I’m freakin’ Saul Goodman. “I’m going to get up quicker,” announces Odenkirk after the cameras stop. “Something about the energy.” He nails the next take. And the next one. And the next one. “I thought it was good,” he tells Gould. “But let’s do another two.”

Gould is thoroughly pleased with Odenkirk’s showcase. Then he notices something: “Did you ruin our nice door?”

“He goes a little cuckoo crazy in this season,” says Odenkirk after wrapping this scene. “But then this moment where he’s caught and he’s in trouble, his brain just goes, ‘Wait a second: I’m back in the legal system. I’m right where I should be. I can manipulate. I can use everything I’ve learned and be myself again! I’m in jail, but I’ve been in a worse jail.’ I mean, it’s worse to not let your personality just naturally exist, cover it up, and hide it. Now he’s out of it. Even though he is in jail, he’s free. He’s free to be this guy again.”

Similar to Breaking Bad, Better Call Saul was plotted season by season, with few long-term plans. How long have the writers known the end of this journey? “We really didn’t know where we were going to take this,” says Gould. “And then season 4 and 5, we started to say, ‘What if it went in this direction?’ It was really an image. It wasn’t exactly what we did. But it gave us a direction to go in.”

They almost had to switch directions when Gilligan walked into the writers’ room one day with a pitch for an alternate ending to 2019’s El Camino: A Breaking Bad Movie, which he was writing and directing. Instead of having Jesse escape safely to Alaska, Gilligan now wondered if Jesse should wind up in prison after doing something noble, but finally he’s at peace. “We all discouraged it,” confesses Gould with a laugh. “We all said, ‘Oh, we like this other idea you have much better!’ I felt the icicles crawling up my back, because I thought that was a better end for us than it was for Jesse…. Walt dies, Jesse gets away, and Saul faces the music — that feels very nice to me. A very nice trilogy.” (In the early stages of brainstorming, Jimmy’s song ended on a sadder and colder note: His reunion with Kim took place before he went behind bars, and he had less peace and more fear in prison.)

The finale shoot, which took a month, had its share of challenges and delays. The producers struggled to find a real courtroom that could double as a federal courtroom. Finally, the New Mexico Supreme Court allowed them to use its courtroom with a skylight, but only on the weekend. After a two-day shoot on Jimmy’s showtime moment in court, “We were supposed to be done with the set and [the producers] announced we needed to come back for just a few pick-up angles,” says Odenkirk. “I turned to Peter and I said, ‘And can I re-shoot the entire scene?’ And people who’d been there all day watching me do this were like, ‘What? You’re going to do it again? No, no! You did it so great! People were crying! No, no, you don’t need to do it again!’ And I said, ‘No, I think I do…. I think I went too quickly, too easily to the well here. And I’d like to do a more restrained version.’ We came back a week later, we got the set back. And you know what was great about it? It was better. It made more sense.”

A giant snowstorm stranded the crew at one location. The prison scene was shot at a real penitentiary, which was “sobering and upsetting,” according to Gould, and “suffocatingly sad,” according to Seehorn. In addition, “We were out in the desert shooting a scene that was supposed to be in the blazing heat, and it was actually damn cold,” reports Gould. “Last season, we shot in the desert and it was way too hot. We could never get it right.”

Until they did, according to Odenkirk. For season after season, the actor didn’t want to know how the show was going to conclude, largely taking the journey script by script. But now that it’s here, how is he feeling? “I love where Peter took it,” he says on that final day of filming. “These things are very hard to land, right? This is completely grounded. Not inscrutable… He wanted to do a very grounded ending that really dug right into the core of what the show is about, and what the character’s experience has been. And for me, playing this guy, I’ve struggled with the blind spot he seems to have. He’s a very emotionally intelligent guy, especially when it comes to other people. He can tell what they want. He can tell how to manipulate them. And I always felt for a guy who’s that emotionally intelligent — I don’t see how he avoids having the self-awareness…. That emotional intelligence that they wrote into this character is on display. And I really love that.”

Greg Lewis/AMC Bob Odenkirk on ‘Better Call Saul’

Standing to the side of the stage, watching Odenkirk finish his solo cell scene, Seehorn believes that the conclusion of this tale is as satisfying as it was ambitious. “On top of the massive jigsaw puzzle that Peter had to figure out to sew up so many stories — while being true to facts that were set by Breaking Bad, facts set by our future episodes with Gene, facts set by our flashbacks — there’s a lot of things he had to answer to,” she says. “And the emotional stories of all the characters? I wasn’t quite sure how he’d be able to do it. Then when I read it, I just thought it was so thoughtful and thought-provoking. It is very much within the storytelling that he and Vince have done the whole time, where the audience is treated as an intelligent, almost collaborator with the story — they’re being asked to contemplate hard questions that don’t have black-and-white answers. So in that way, I found it perfect. As a fan of the show, I would be so happy with this ending — as gut-wrenching as parts of it are.

“It’s certainly poignant,” she continues. “But it is more hopeful in a human way than, say, [how] Breaking Bad ended. [Laughs] Peter said that it would be great if it inspired people to continue the story in their head, and that’s what it does — which is different than insisting upon not answering something to not sew it up. It’s much more: ‘I wonder what the next conversation is.'”

Conversation on the set is increasingly turning to the End. There are just a couple of hours left in the day, and emotions are starting to leech into the proceedings. Executive producer Melissa Bernstein tries to wrap her head around the end of this decade-and-a-half franchise. “It’s like, ‘Can we destroy these sets now?’ Can we? I don’t know,” she says. “That makes it feel very final. A couple of the crew members have come up to say goodbyes, like, ‘I might not ever see you again.’ And I’m like, ‘That seems preposterous!'” Like the others here who have been through Bad and Better, she can’t believe that lightning struck with one underdog drama, let alone a second glorious bolt. She wistfully surveys the packed-up sets: Saul’s pillars stand sadly by themselves over here, and oh, by the way, Jesse worked as a meth-making prisoner right over there.

The set is less crowded today than one might expect, but some actors have already moved on to new projects, and there are also COVID protocols. Odenkirk and Seehorn — who get swabbed up the nose a few times during the day — use their free minutes to say goodbyes to extras, commiserate with crew members, and (try to) crank out a few thank-you notes. “I can’t bring myself to write Bob’s card yet,” says Seehorn. “I don’t know that I ever will. I think he’s just stuck with me for life.”

Seehorn has been grappling with the weight of the day, attempting to use a form of emotional jujitsu on herself. “I’m an incredibly sentimental person,” she says. “I’ve honestly been trying to trick myself into thinking it’s the first day.” And how’s that going for her? “It’s helping some. In the excitement of today, it’s just too hard for me to think about an ending ending. I love all these people. This is my favorite role in my life and the best storytelling ever.”

That struggle becomes quite evident when Odenkirk and Seehorn finish rehearsing their final scene and answer a simple but loaded question from a reporter: Do they already feel nostalgic in this moment, with memories and emotions rushing into their head?

“Absolutely nostalgic,” says Odenkirk. “This is heavy-duty stuff. Heavy duty. We’ll be talking about this for years to come.”

“I mean, it’s hard,” says Seehorn softly.

“When you’re in a great scenario, especially if you’re older and you’ve been through a lot of stuff, some part of you knows you can’t value it enough, and that it won’t be replaced anytime soon,” says Odenkirk. “And you don’t know what to do to appreciate it enough. This will resonate through the rest of my life. We’re very lucky. We’re very lucky. I mean, it’s really—”

“I don’t think I can do this right now…” Seehorn interjects, getting up from her chair and walking away in tears. Breaking up onscreen was hard enough; no longer getting to act opposite each other represents a greater death.

Greg Lewis/AMC Rhea Seehorn and Bob Odenkirk

After the final take of that reunion smoke, the tears flowed, as did the speeches from Odenkirk, Seehorn, and Gould. Odenkirk later recalls telling Seehorn in their final hug: Thank you for being so f—ing great. And what did Seehorn say? “I said, ‘I love you and I am incredibly proud of what we’ve done,’ and that I hoped he was proud of his own work,” she shares. “I told him, ‘I think what you’ve done is incredible. It’s just one of the most incredible performances, and I’ll miss being front row to that.'”

Anything else? “I mean, the other part is we then said, ‘Okay, are you picking food up at Whole Foods?’ and drove home to the same house,” Seehorn says with a laugh. “So it wasn’t that big of a goodbye.”

Harder for her was the next day. Sometimes the actress ships her car back to Los Angeles at the end of a season. Sometimes she drives it back. This was definitely a time for the latter. “I cried all the way home,” she shares. “I knew I was tired, but I wanted that 12 hours to think — to not entirely let go, but let go enough that I can be proud of it instead of holding on so tightly that you can’t enjoy releasing it to the world, you know? And knowing that it’s a book where they wrote the last chapter as perfectly as it could be written in my opinion.”

Odenkirk processes his morning-after thoughts. “I was thinking, ‘It’s going to be a long time before I let go of the feelings and this character,'” he says. “Even though I had to say goodbye to it in the real world, that guy’s going to stay with me for a long, long time — and feelings about Jimmy and Kim and the struggle that character had inside himself.” That said, like Jimmy, he found himself secreting away the more difficult feelings until they burst to the surface against his will. “I act like I don’t care, and try to get swept up in something else,” says the actor. “And then very slowly over months to come, I get hit a little more until I realize I’ve been a f—ing mess and I just wouldn’t acknowledge it. And that’s what’s happening again.”

As everyone piled out of Albuquerque, they took something with them. Sure, the memories of a lifetime. But also, a token of their desert adventure. Seehorn left with Kim’s shoplifted earrings and necklace. (But she didn’t steal them; she asked permission from costume designer Jennifer Bryant.) Odenkirk took Jimmy’s Panavision director’s hat. (“It’s the only time the character was really happy,” he says.) Esposito scooped up a handful of pebbles from Gus’ showdown with Lalo in the under-construction superlab. (“I realize now I should have just gotten a bucket of dirt, because it meant something for Gus, deep down, to make that, to create that lab under the laundry is a brilliant idea,” says Esposito, tearing up. “And to be able to do it with German engineering is even more fascinating, so that was really special to me.”)

Mando kept the silver ring with a lion’s claw; he bought it in a Navajo community in the desert and Bryant agreed that Nacho should wear it on the show. (“It represented sort of that lion heart that Nacho has,” he notes.) At one point, McKean swiped some books from Chuck’s great room — a Great Mysteries of 1948-type tome — but he brought them back after he read them. Also, “They’re threatening to send me that gigantic portrait [of Chuck], but they gotta think of something else to do with that,” he quips. “That guy’s gone.” Meanwhile, Dalton is never far from his memento. In fact, it’s still on his face. “The only thing that I kept of Lalo, which worked out for me, was the mustache,” he says. “I never had one before. Maybe I’ll keep it for a little bit.”

***

At one point on the final day of filming, Odenkirk stares longingly/amusedly at the folded-up, deconstructed Saul Goodman office. “The first day I walked into this stage, I did the little commercial — that’s the first thing I did,” he says. “Maybe I played it a little too broadly, but it was just a loud lawyer commercial. We shot that over there. And then right here was the law office set.” He points to the dismantled columns from the cathedral of justice. “I did the scene the same day with Bryan where [Saul] drops his façade and tells Walter White, ‘This isn’t who I am, this is a made-up thing.'” Odenkirk is interrupted by a staffer who administers an up-the-nose COVID test, and without missing a beat, he continues: “It was all so foreign to me. My career hadn’t really groomed me for the drama of Breaking Bad. And I really thought, ‘There’s a chance that what happens is they call me after I shoot and they go, “We’re going to have to replace you,” and I wouldn’t be insulted.’ I would’ve just been like, ‘Well, you guys were crazy to try me, you know?'”

A little later, Gould also finds himself drawn to those pillars. “I have such an emotional attachment to that set,” he says. “That was my third episode of television that Saul Goodman showed up in. We built that set. And it’s a crazy set. When Breaking Bad was over, I was sure that was it. We’d never see it again. And the fact that it’s exactly the same set, it was stored at Sony [the studio that produced the franchise] all these many years. So I don’t know. I look at it and I feel sad in a way, but you can’t help wondering: The set still exists. You never know what might happen! This is the end, but you never know, maybe not the end of the end. Who knows?”

Greg Lewis/AMC/Sony Pictures Television Bob Odenkirk as Saul Goodman on ‘Better Call Saul’

As in, one day the franchise will add another chapter in some form, as it has done twice before? “The truth is, we’re leaving, and Jimmy and Kim are still both alive,” tease Gould. “And, you know, as they always say in my family, ‘When there’s life, there’s hope.'”

Today, six months later, the door is still cracked open, but it sounds like no one is going through it for a while. Gilligan recently told reporters that “you can’t keep putting all your money on Red 21.” “Sometimes it’s good to know when to leave the party,” sums up Gould. That said, “This world is so rich and these characters are so layered and these actors are so wonderful that we’d be crazy not to at least wonder and daydream about what the other possibilities are…. The dreams I have about these characters and the fantasies seem as real to me as my real life. Almost.”

The story lives on in Odenkirk’s head. Actually, he’s got it mapped out rather vividly. “I think she comes to see him once a year — every other year, at the least,” he explains. “And I think he helps a bunch of guys in prison to get out who are innocent, or he helps shorten their sentences. He gets treated really well. I think he’s kind of the king of the prison because he’s a really, really good lawyer, and a great lawyer for the kind of people in there.”

Seehorn still holds a flickering candle for the dream team that was Kim and Jimmy. “I definitely think that she loves him,” he says. “And I don’t just mean as a friend. I think that she still deeply loves him.” And, yes, since, you keep asking, she’s totally up for the Kim spin-off. “If they want to do one, I will do it!” she exclaims. “But if we get to do it, I hope it’s not, like, 80-year-old Kim. I’d like to do it while I’m still a little spry.” But then again, who knows? In about 30 years, someone may be getting out for good behavior….

Related content: