The birds no longer sing, and the herbs no longer grow. The fish no longer swim in rivers that have turned a murky brown. The animals do not roam, and the cows are sometimes found dead.

The people in this northern Myanmar forest have lost a way of life that goes back generations. But if they complain, they, too, face the threat of death.

This forest is the source of several key metallic elements known as rare earths, often called the vitamins of the modern world. Rare earths now reach into the lives of almost everyone on the planet, turning up in everything from hard drives and cellphones to elevators and trains. They are especially vital to the fast-growing field of green energy, feeding wind turbines and electric car engines. And they end up in the supply chains of some of the most prominent companies in the world, including General Motors, Volkswagen, Mercedes, Tesla and Apple.

But an AP investigation has found that their universal use hides a dirty open secret in the industry: Their cost is environmental destruction, the theft of land from villagers and the funneling of money to brutal militias, including at least one linked to Myanmar’s secretive military government. As demand soars for rare earths along with green energy, the abuses are likely to grow.

“This rapid push to build out mining capacity is being justified in the name of climate change,” said Julie Michelle Klinger, author of the book “Rare Earths Frontiers,” who is leading a federal project to trace illicit energy minerals. “There’s still this push to find the right place to mine them, which is a place that is out of sight and out of mind.”

The AP investigation drew on dozens of interviews, customs data, corporate records and Chinese academic papers, along with satellite imagery and geological analysis gathered by the environmental non-profit Global Witness, to tie rare earths from Myanmar to the supply chains of 78 companies.

About a third of the companies responded. Of those, about two-thirds didn’t or wouldn’t comment on their sourcing, including Volkswagen, which said it was conducting due diligence for rare earths. Nearly all said they took environmental protection and human rights seriously.

Some companies said they audited their rare earth supply chains; others didn’t or required only supplier self-assessments. GM said it understood “the risks of heavy rare earths metals” and would source from an American supplier soon.

Tesla did not respond to repeated requests for comment, and Mercedes said they contacted suppliers to learn more in response to this story. Apple said “a majority” of their rare earths were recycled and they found “no evidence” of any from Myanmar, but experts say in general there is usually no way to make sure.

Just as dirty rare earths trickle down the supply chains of companies, they also slip through the cracks of regulation.

In 2010, in response to war in the Congo, Congress required companies to disclose the origin of so-called conflict minerals — tantalum, tin, gold and tungsten — and promise their sourcing does not benefit armed groups. But the law does not cover rare earths. Audits are left up to individual companies, and no single agency is held accountable.

The State Department, which leads work on securing the U.S. rare earths supply, did not respond to repeated requests for comment. But experts say the government weighs the regulation of rare earths against other green goals, such as the sales and use of electric vehicles. With ongoing negotiations in Congress, the issue has become increasingly touchy, they say.

Rare earths are also omitted from the European Union’s 2021 regulation on conflict minerals. A European Commission statement noted gaps in oversight of the supply chain stretching to Europe, and said “it is yet unclear how” a Chinese push to regulate rare earths will work.

With no regulation or alternatives, companies have quietly continued shipping rare earths without environmental, social and governance audits, known as ESG.

“What would be the result if now the world would say, ‘We want to do ESG audits on all rare earths production’?” said Thomas Kruemmer, director of Ginger International Trade & Investment, which does mineral and metal supply chain management. “The result would be that 70% of production would need to be closed down.”

___

The story of rare earths is one of a naked grab for resources while leaving the wreckage to other countries.

The United States offshored its rare earths mining to China in the 1980s because of environmental and cost issues. China’s leader at the time, Deng Xiaoping, declared rare earths China’s answer to “oil in the Middle East.” Tens of thousands of Chinese in the countryside discovered that they could make more in a month of mining than years of farming.

For decades the industry prospered. China became the world’s foremost miner of rare earths. A Beijing magazine called the profits “more addictive than drugs.”

Then, stung by public criticism, officials in Beijing declared war on the country’s dirty industries, including rare earths mining. At a 2012 press conference in Beijing, a top Chinese industry official brandished photos of the devastation — pockmarked land stripped bare of vegetation.

Caught in the crossfire were miners like Guo, who asked to be identified by his last name only.

For years, Guo, a former car repairman, earned a handsome living after joining the booming rare earths industry in his native Jiangxi province. Then Beijing began enforcing some of the world’s strongest environmental laws, shutting down mom-and-pop operations like his. Chinese satellites now snap photos from space, hunting for hidden mines.

But even while the supply from China is now monitored, the global demand for rare earths is expected to explode by 300% to 700% by 2040, according to the International Energy Agency. The proposed Inflation Reduction Act in the U.S. would increase demand even more by subsidizing the sale of electric vehicles in one of the world’s largest markets.

“The disturbing reality is that the cash that fuels these abuses ultimately comes from the world’s fast-growing demand for these minerals, driven by the scaling up of green energy technologies,” said Clare Hammond, a senior researcher at Global Witness, which also conducted field work in Myanmar.

China is also responding to competition from Europe and its greatest rival, the United States, which has called its dependence on rare earths from China a “national security risk.” Concerned that its shrinking reserves could allow Western countries to break its stranglehold on the industry, China encouraged companies to look abroad.

“Environmental controls have become much stricter,” said a government trade researcher, who declined to be named because he was not authorized to speak to the media. “That’s why imports have increased. It’s better to get rare earths from abroad.”

The Chinese foreign, industrial and environmental ministries and the Jiangxi regional government did not respond to requests for comment.

As mines in China shuttered, ore prices rose. In neighboring Myanmar, home to some of the world’s richest deposits of what are known as heavy rare earths, opportunity beckoned. Thousands of Jiangxi miners streamed across the border.

“It reminds me of the European colonial attitudes towards Africa,” said an industry analyst, speaking on condition of anonymity to avoid damaging ties with the Chinese government. “You just can’t be relying on third-world-type mining practices in a dictatorship like Myanmar. It’s not sustainable.”

That does not bother Guo.

In 2019, he got a call. An old contact was opening up shop in Myanmar and needed a technician. Would he like to go?

Guo said yes, joining what he describes as a modern-day gold rush. He recounted primitive working conditions, including clouds of mosquitoes and nights spent burning logs in ramshackle cabins. The miners dug hundreds of feet deep with shovels and their bare, callused hands.

“I lived in a virgin forest, I lived like a savage,” he said.

He and other Chinese workers in Myanmar described a web of small, unlicensed private mines that sell to China’s big state-owned mining conglomerates – directly or through trade intermediaries. When cash changes hands, few questions are asked.

“I’m only responsible for digging the mountain up and selling it,” Guo said. “The rest is none of my business.”

Since 2015, imports from Myanmar have grown almost a hundredfold, according to UN trade data. Myanmar is now China’s single largest source of heavy rare earths, making up nearly half of the supply, according to Chinese customs data and expert estimates.

A few years ago, there were just two or three mines in Myanmar, then dozens. Today there are hundreds, and Guo guesses there may soon be thousands. At this pace, he predicts, it won’t be long before Myanmar’s rare earths are all gone.

But Guo cares little about preservation or politics.

“They talk about future generations, I’m talking about survival today,” he said. “We just see if we can make money. It’s that simple.”

__

There is a name for what Myanmar has become: A “sacrifice zone,” or a place that destroys itself for the good of the world.

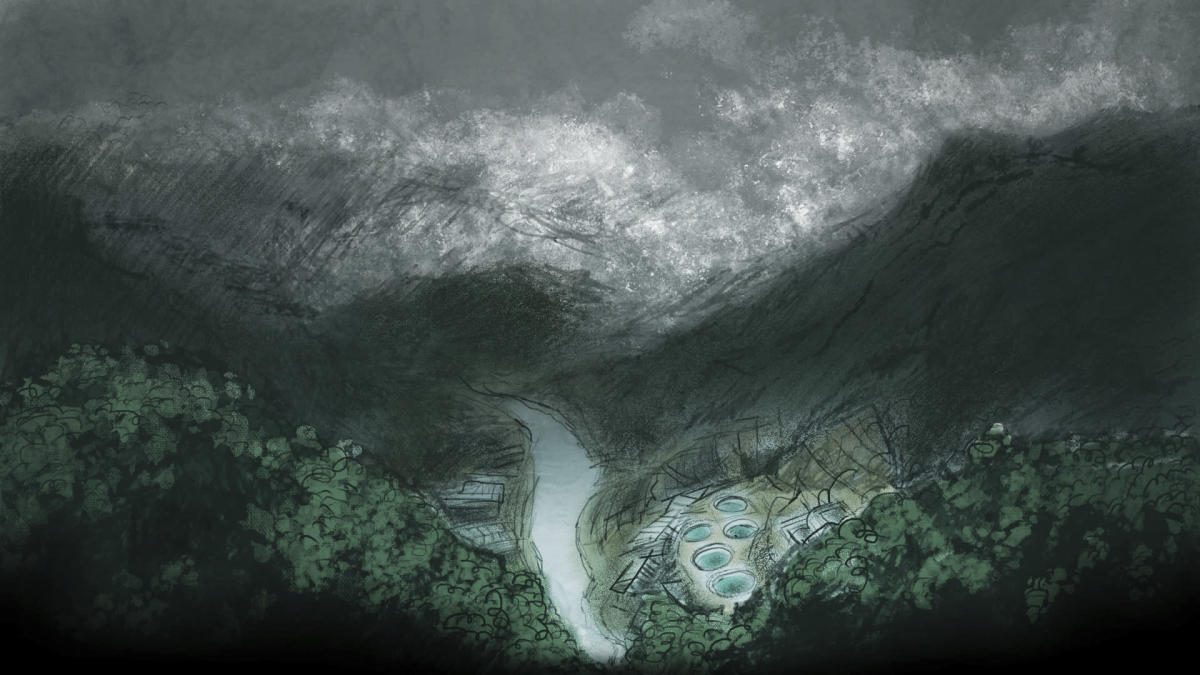

The sacrifice is visible from the air, in toxic turquoise pools that dot the landscape covered by mountain jungles just a few years ago. Since rare earth clays in Myanmar are soft and near the surface, they can easily be scooped into these pools of chemicals. Satellite imagery commissioned by Global Witness showed more than 2,700 of these pools at almost 300 separate locations.

The leaching agents have tainted tributaries of Myanmar’s main river, prompted landslides and poisoned the earth, according to witnesses, miners and local activists. Water is no longer drinkable, and endangered species such as tigers, pangolins and red pandas have fled the area.

A villager who lives along a river some 15 miles from the center of the mining sites said his wife used to catch and sell fish. Now the few they can catch make them ill, so they must buy from elsewhere at higher prices instead. Every time he enters the water, his feet feel itchy.

“There are no fish along the creek, not even small fishes,” said the villager, who asked to be anonymous for his safety. “Everything went extinct.”

Militias are rampant in these northern forest frontier areas, with at least one tied to the Border Guard Force backed by the Myanmar military, or Tatmadaw. Since seizing power last year, the Tatmadaw is under international sanctions for human rights abuses, which means the rare earths money it gets from the militia may be going into a violent crackdown against civilians.

With the armed militias in control, villagers have no recourse to defend their land.

When village leaders filed a complaint about the effects of rare earth mining and testing on land needed for black cardamom, walnuts and livestock, a high-ranking militia leader aligned with the Border Guard Force angrily summoned them. He said rare earth mining would proceed with or without their agreement.

“You, village leaders, should solve this issue,” he yelled as he pointed to the leaders, according to a recording of the January meeting obtained by Global Witness, which was shared with and verified by the AP. “Otherwise, I’ll have to start shooting and killing people. Do not underestimate me. I am not a child – this is not child’s play.”

The Myanmar military, militia-owned mining companies and militia leaders did not respond to requests for comment.

In the meantime, mining projects continue to get ever closer to the land villagers are trying to protect.

“We dare not complain,” said a villager, who also asked to be anonymous for his safety. “If we say something … they beat us. We don’t want to be in prison.”

The militias and warlords have turned Myanmar’s frontier with China into a modern-day wild west, with each tiny fiefdom demanding a cut of the profits that flow through its land.

“(The money) has to be going to people that are not nice people,” said an executive at a Chinese magnets maker, who declined to be named to speak on a sensitive topic. “There’s no way out of it.”

For Dong, a Chinese miner, the hundreds of dollars he hands to the armed men lining the roads in Myanmar are the price of doing business.

“To enter Myanmar, you pay,” he said, declining to give his first name to speak on a sensitive topic. “It’s all about the money.”

Dong said police have told him that the rare earths he extracts can only be sold to China, not to the Americans or Japanese, because they are China’s strategic resources. He is under no illusions about the damage from acids so strong that they corrode the shovels of his bulldozers and excavators – something he’d never seen before.

“This stuff is unbelievable,” he said. “It’s definitely polluting.”

___

As rare earths from Myanmar travel around the world, they pass through many hands.

The most destructive mining is for heavy rare earths, which are critical to make powerful magnets heat-resistant. Ores are trucked across the border from illicit mines in Myanmar to southern China, where state-owned companies buy them up in sacks by the thousands. Among them: Minmetals, China Southern Rare Earth, and Rising Nonferrous Metals.

Some 70% of China Southern’s rare earth ores came from Myanmar, with the rest from recycling, Jiangxi customs official Liu Jingjing wrote in a paper. China Southern, among the world’s largest processors of heavy rare earths, has no active mining in China, according to Liu’s paper. A company post highlighted how it is “seizing overseas rare earth resources” and “opening up” imports from Myanmar.

Minmetals, another major producer, warned shareholders in recent annual reports that it relied heavily on imports, as its one major mining project in China didn’t produce enough. Rising Nonferrous, the third company, wrote on their website in 2020 that their trading subsidiary had won approval from Chinese customs to import Myanmar heavy rare earth ores.

All three companies did not respond to calls, emails and faxes requesting comment.

Those companies in turn supply three major magnet companies: Yantai Zhenghai Magnetic Material, JL MAG, and Zhong Ke San Huan, public agreements show. Rising Nonferrous also supplies Guangdong TDK, a joint venture with Tokyo-based TDK, one of the world’s largest manufacturers of cell phone, laptop, and hard drive components and a supplier of Apple and Samsung. TDK and the magnet companies did not respond to requests for comment.

As the ore is transformed into magnets, it is separated, refined and melted, according to interviews with miners and magnet engineers. Along the way, materials from different sources often get mixed, making it difficult to track any particular shipment of rare earths from Myanmar to a specific batch of magnets.

Chinese magnet makers often don’t know where their rare earths come from because many multinational companies don’t ask, an engineer at one company noted.

“There’s never been like, where do you get your rare earth?” said the engineer, declining to be named to speak candidly. “There should be concern, but there’s no concern within the industry.”

The magnet companies go on to supply intermediaries like components manufacturers and trading companies as well as big brands. The rare earths can pass through many more tiers of suppliers before reaching a consumer.

“The transparency in this industry is just so poor that the companies don’t know,” said Kristin Vekasi, a professor studying rare earth sourcing at the University of Maine.

Among global carmakers, GM, Volkswagen, and Mercedes said they expect suppliers to adhere to codes of conduct and due diligence, and Mercedes added that they were designing new motors to eliminate heavy rare earths. Ford said they conduct audits and request suppliers to identify sourcing.

Hyundai denied using rare earths from Myanmar, and Stellantis said that “to the best of Stellantis’ knowledge,” their rare earth supply chains only involve operations in China. Some auto parts makers, including Bosch, Brose and Nidec, also said they were assured by the magnet companies that their components were free of rare earths from Myanmar. Others, such as Continental AG and BorgWarner, said they expected suppliers to adhere to their codes of conduct.

However, only an order from the Chinese government could force companies to separate rare earths from Myanmar and China, according to Nabeel Mancheri, secretary general of the Rare Earth Industry Association. The group is trying to build a blockchain-based verification to link up international customers with the Chinese companies “upstream.”

“Nothing exists on auditing the Chinese supply chain,” he said. “Downstream players simply rely on whatever certificate they get from Chinese companies.”

Among electronics giants, Samsung said they did not tolerate rights violations or environmental damage but did not answer other specific questions about their suppliers. Toshiba, Panasonic and Hitachi did not comment on suppliers but said they would suspend working with businesses violating human rights.

Thyssenkrupp said it had “initiated measures” to find out more about the origin of the minerals for its magnet supplier. Other machinery manufacturers like Mitsubishi did not respond.

Among wind turbine manufacturers, Siemens Gamesa, which has projects in the United State and Europe, said it audits immediate suppliers and is preparing to trace those further upstream. It said “supplier feedbacks” showed only rare earths from China. Other wind companies, like Xinjiang Goldwind, did not respond.

But Klinger, the expert on illicit minerals tracing, said the only way for a company to be certain to avoid rare earths from Myanmar is to have their supply chain “entirely outside of Myanmar, China and potentially outside Southeast Asia.” She said there are cleaner ways to mine, but they cost more – a huge hurdle in the cutthroat world of commodities.

Mike Coffman, a former congressman who pushed for the original U.S. conflict minerals rules a decade ago, said he would like to see an expansion of the domestic supply of rare earths minerals, which is now before Congress. And U.S. Sen. John Cornyn, a Texas Republican, introduced a measure this year aimed at reducing U.S. reliance on China for rare earths and other critical minerals.

However, alternatives are still a long way in the future. In 2022, the U.S. and Australian governments both backed domestic rare earths projects with multimillion dollar financing, but facilities are years and tons of metals behind China’s current capacity.

Other countries with rare earths deposits are reluctant to mine them. Greenland’s parliament last year voted to halt a rare earth mining project, and efforts to develop a promising deposit in Sweden stalled because of local objections.

In the meantime, villagers still protest in one area in northern Myanmar where the black cardamom and walnuts grow – for now. Standing in the green mountains under a tree, a villager made it clear why they continue to raise their voices even when there’s been no recourse for others just a few mountains away.

“They are mining rare earth everywhere and we are no longer safe to drink water,” she said. “There is nothing to support the children. Nothing to eat.”

___

AP researcher Si Chen, investigative journalist Martha Mendoza and AP Diplomatic Writer Matthew Lee contributed to this report.

____

To contact the AP’s investigations team, email investigative@ap.org.