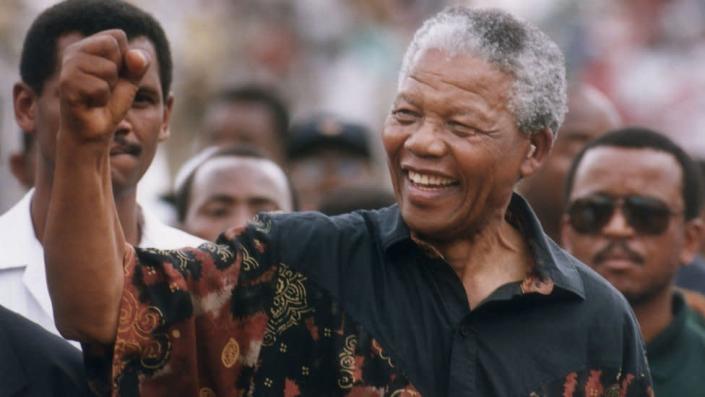

In the autumn of 1994, Nelson Mandela, who had been a political prisoner in South Africa four years earlier, was moving into his new presidential office at the Union Buildings in the capital, Pretoria.

The nation stood at the unfamiliar intersection between hope and uncertainty.

That was because apartheid, a decades-old system of governance that pitted citizens against each other along racial lines, had just collapsed.

It was time for people from all walks of life to hold hands and forge a new path towards peace and reconciliation, following years of bloodshed.

But no-one knew exactly what the promised land looked like, not even Mandela himself.

One of the first steps the new government took was to assemble an elite security detail that would protect the head of state, as he assumed his new role.

In an extraordinary move, Mandela’s administration merged a group of white officers from the notorious apartheid police force with black political activists.

In today’s terms, it would be like asking Russian and Ukrainian or Palestinian and Israeli armies to join forces.

“I looked at my comrades and said: ‘How do you trust these guys? How are we going to work with these guys?’ We were sworn enemies and it was difficult for all of us,” Jason Tshabalala, a black member of Mandela’s team of bodyguards, tells the BBC Africa daily podcast.

Mr Tshabalala was born and raised in the township of Soweto, where Mandela once lived.

He took a decision in the 1980s to actively campaign against apartheid, after his mother was fired from her job for chewing gum during working hours.

This personal incident made him acutely aware of racial discrimination and the unfairness in his country.

He later joined the liberation movement, the African National Congress (ANC), which sent him to countries like Zambia and Russia, for extensive academic and military training.

For months, he handled different types of weapons, preparing to fight a racist system that claimed the lives of some of his closest comrades.

But with apartheid coming to an end in 1994, fate placed Mr Tshabalala in an incredibly awkward position.

He was now required to put his anger towards white domination aside, and work side-by-side with the same policemen who represented everything he feared and hated.

“There were fundamental trust issues when we started the amalgamation process,” he says, his face suddenly tensing up as he talks about this period of his life.

At one point, the black bodyguards wondered if their white counterparts were planning to harm their political master, Mandela.

“You know, you always had that in mind to be quite honest. ‘How do I trust these guys when they locked him up for all these years?’ Some of them were involved in all kinds of criminalities while they were defending apartheid. So, it did cross our minds.”

‘There to do a job’

But Gert Barnard, a white member of the presidential protection unit, did not see things that way.

His responsibility, he says, was to catch a bullet for the man who was fondly known as Madiba.

“I spoke to a number of my colleagues during that time. I asked: ‘Has it ever crossed your mind to take out Madiba [Mandela]?’ I cannot recall any of the apartheid police guys that ever said, ‘I was thinking of it.’ We were there to do a job. We were professionals.”

Mr Barnard was an experienced police officer who previously guarded two apartheid-era heads of state, FW de Klerk and PW Botha.

He was born and raised in a conservative Afrikaner family in the mining town of Stilfontein, in the North West Province.

“I saw how my dad came home and whenever a black guy wanted to clean the garden he would say, ‘no! no!'” His father would then use a derogatory word for black people.

“I obviously saw that and I didn’t want to fall into that same trap of not respecting people.”

Mr Barnard says that he was guided by his strong Christian values, which discouraged racial hatred.

Fast forward to 1994, and his assertions were put to the test.

He had to report for duty with the same people he was once told were planning to attack and drive white South Africans to the sea.

“There was animosity. We interrogated them when they were still called terrorists, and now we had to work together.”

On their very first day at work, these two groups of bodyguards made their feelings known.

The black officers closely surrounded Mandela, while the white ones stood a few feet away.

The president almost immediately noticed these racial tensions and sat them down.

Mr Tshabalala remembers what Mandela told them.

“He said: ‘Guys, I want you to ensure that you work together. We’ve gone through a difficult period in our country. We are building a country now. Part of building a country is for us to reconcile and work with all South Africans’.”

Mandela’s charm

The team reluctantly and grudgingly followed their boss’s orders.

But of course there was no escaping Mandela’s charm, sincerity and rare ability to get two clashing factions to work together.

Weeks into their gruelling schedule, members of the protection unit began warming up to each other.

In that process, they found out how tricky it was to work for Madiba.

“I remember one incident when our motorcade was driving to the office, and it was raining. I think he noticed a lady who was stuck on the side of the road. All of a sudden he said: ‘Stop!'” Jason laughs, as he recalls this moment.

Mandela ordered his bodyguards to help the stranded motorist.

“So, you can imagine the whole protection detail with suits and ties, helping this lady in the rain. That was Madiba for you”.

Mr Barnard says he was always surprised at how engaged his boss was on a personal level.

“He wanted to know what is happening in our lives. We had a unit in Cape Town and in Pretoria. Each unit had two teams looking after Madiba. So, in one team there were about 16 to 18 bodyguards, and Madiba knew each and every person. He knew their wives, he knew their children.”

Mandela died peacefully at his Johannesburg home on the 5th of December 2013.

If he was still alive, he would have turned 104 years old today, 18 July.

Meanwhile, Jason Tshabalala and Gert Barnard went on to serve as security officials in the private sector.

To this day, they remain friends who are part of the same WhatsApp group of former bodyguards.