“In order to do my job,” Ben Stiller, as Tom Cruise’s stunt double Tom Crooze, muses in a video made for the 2000 MTV Movie Awards, “I have to ask myself: Who is Tom Cruise? What is Tom Cruise? Why is Tom … Cruise?”

This is a tricky line of questioning.

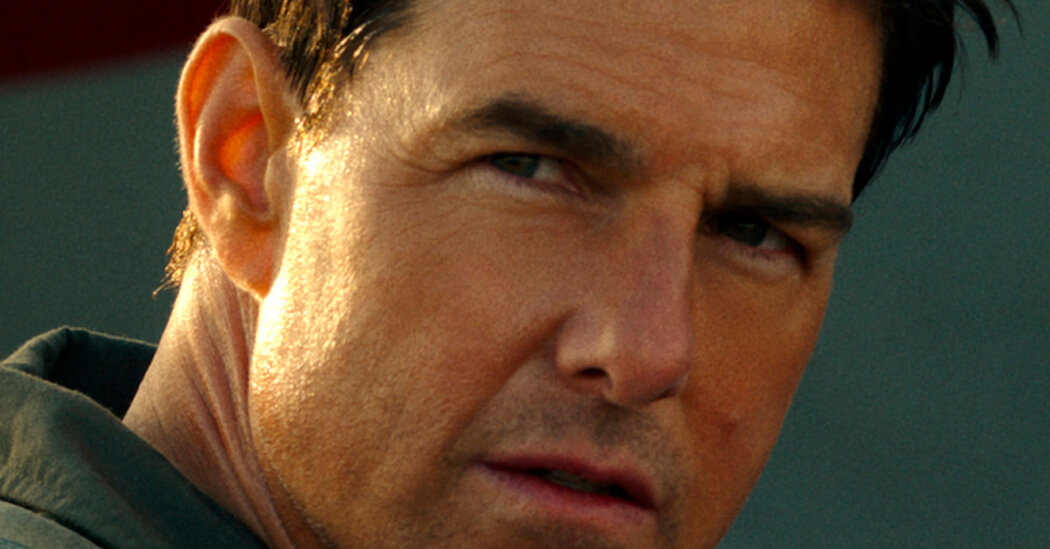

Onscreen, Cruise is unmistakably our biggest movie star, as the New York Times reporter Nicole Sperling recently explained — the last true exponent of a century-old studio system that has been steadily eroded by the rising forces of franchise filmmaking and streaming. His powerful charisma and daredevil stunt work have combined, yet again, in his latest hit, “Top Gun: Maverick,” bringing it past the $1 billion mark.

Offscreen, Cruise is elusive. He is the frequent public mouthpiece for a cryptic, controversial religion that seems harder to understand the more he talks about it. He is intensely secretive about the details of his private life. Even when he makes the occasional effort to seem like an ordinary, relatable guy, he winds up sounding like an A.I. approximation of one. Asked by Moviebill magazine to describe his most memorable filmgoing experience, Cruise couldn’t name one. (“I love movies,” he said, very normally.) When asked which team he was rooting for at a Giants-Dodgers game he attended last fall, he replied, “I’m a fan of baseball.”

It can be hard to reconcile these disparate sides. So it is worth considering the question: Who is Tom Cruise?

Much of his early success as an actor, through the ’80s and ’90s, was predicated on a certain down-to-earth charm. The sexed-up, troublemaking young Cruise of “Risky Business”; the guileless, endearingly naïve Cruise of “Cocktail”; and the tenacious, morally principled Cruise of “Jerry Maguire” each relied on his ability to convincingly embody the American Everyman, the sympathetic heartthrob the audience could desire or root for. Around the turn of the century, he complicated that image by appearing in more challenging, less accessible films, like “Eyes Wide Shut” and “Magnolia.” Auteurs like Stanley Kubrick and Paul Thomas Anderson helped showcase Cruise as a serious actor, capable of delivering subtle, nuanced performances.

‘Top Gun’: The Return of Maverick

Tom Cruise takes to the air once more in “Top Gun: Maverick,” the long-awaited sequel to a much-loved ’80s action blockbuster.

- A Triumphant Return: At a time when superheroes dominate the box office, the film industry betis betting on the daredevil actor to bring grown-ups back to theaters. It paid off.

- Review: The central question posed by the movie has less to do with the need for combat pilots in the age of drones than with the relevance of movie stars, our critic writes.

- Your Burning Questions: How similar is it to the original? Who’s back? Who’s absent? We have answers.

- Anatomy of a Scene: The movie’s director, Joseph Kosinski, on the making of a key scene in “Top Gun: Maverick.”

He has moved away from romance, drama and the independent art house. Over the last decade-plus, he has become more firmly entrenched in the action-adventure genre, perfecting the summer tentpole blockbuster. His performances tend to emphasize his easy charisma and powerful athleticism, but Cruise still brings to these roles a touch of the same delicate charm and actorly nuance of his dramatic fare. You see it in the breezy, naturalistic chemistry he shares with Jennifer Connelly in “Maverick,” and in the jaded, world-weary intensity he has carried through the last couple of “Mission: Impossible” sequels. My favorite recent Cruise performance was from the underrated “Edge of Tomorrow” (2014), in which he plays a cowardly, sniveling politician forced to relive the same deadly battle over and over again — a playful sci-fi take on “Groundhog Day” that found the actor playing against type to delightful effect.

But that’s just part of the story. One of the defining features of the last decade of his career is a level of quality control for which he himself is chiefly responsible. It’s not that he is incapable of making a bad movie: “The Mummy” (2017), Universal’s failed attempt to kick off an entire “Dark Universe” of big-budget creature features, made that clear. But recent Cruise films have in common a degree of ambition and enthusiasm that is rare in today’s blockbuster landscape, and when everything works, that effort pays off enormously. You will not see Cruise phoning in a performance. You get the sense that he treats every movie he does these days as if it were the most important one he has ever done.

The results of this commitment have a way of feeling almost miraculous. How could anyone have expected “Top Gun: Maverick,” a sequel to a 35-year-old action movie with a rather cool critical reputation, to be not only far superior to the original film, but also one of the finest action films in many years? But then you read about Cruise’s dogged insistence on keeping everything as real as possible — demanding a minimum of computer-generated effects, forcing himself through arduous flight training, encouraging his co-stars to bear G-force speeds until they literally threw up. Some of Cruise’s co-stars over the years have characterized his obsessiveness as extreme to the point of what sounds like cinematic despotism, and it’s true that it would probably be easier, and cheaper, to do much of this in front of a green screen. But that’s not Cruise. When it comes to this stuff, he cares too much.

“Mission: Impossible” was a slick espionage film, directed by Brian De Palma, based on a TV series from the 1960s. How is it possible that it yielded five sequels, and how is it conceivable that the sequels keep getting better, culminating in “Mission: Impossible — Fallout” (2018), which is pretty much an unqualified masterpiece? (The final two installments, “Dead Reckoning Part One” and “Dead Reckoning Part Two,” are due in 2023 and 2024.) Again, the credit should go mainly to Cruise, who, for the sake of our entertainment, will happily climb the world’s tallest building, hold his breath for six and a half minutes, or jump out of an airplane with the cameraman.

But Cruise’s devotion to the movies runs deeper, if that’s possible. It’s a devotion to the Movies with a capital M. As A-list talent flocks to deep-pocketed streamers with blockbuster ambitions, Cruise has remained adamant that he will not make a movie for the likes of Netflix or Amazon Prime Video, refusing to negotiate on the possibility of a V.O.D. premiere for “Maverick” earlier in the pandemic. (“I make movies for the big screen,” he explained.) His interest in preserving that traditional cinematic experience shines through in the colossal scale of the productions themselves, so that when Cruise is looming over you in immense, Imax dimensions, he feels every bit as big as the image. It’s a reminder that so much of what we watch is tailored to the streaming era — a mass of “content” designed to play as well on a phone as on the big screen. For those of us who still care deeply about the cinema and fear for its future, Cruise’s efforts feel invaluable.

It’s also a reminder of why we go to the theater to see Tom Cruise movies — to see Tom Cruise himself. We can still be tempted to the cinema by the names on the marquee, but as franchises have become the dominant force in the business, the persuasive power of those names has declined. The supremacy of proven, bankable intellectual property today over the traditional star system has meant that we are more likely to seek out Spider-Man, Thor and Captain America than Tom Holland, Chris Hemsworth and Chris Evans; the actor in the cape is more interchangeable than ever. With Cruise movies, that relationship is inverted. Does anyone particularly care about the adventures of Ethan Hunt? (That’s the name of his character in “Mission: Impossible,” in case you forgot.) Hunt is just another name for the man we really care about: Cruise, plain and simple.

Cruise has all of the qualities you want in a movie star and none of the qualities you expect of a human being. As a screen presence, he is singular; as a person, he is inscrutable. But it’s his inscrutability that has allowed him to achieve a sort of clarified, immaculate superstardom, one that exists almost entirely in the movies, uncontaminated by mundane concerns. Cruise the star burns as bright as any of his contemporaries, and far brighter than any who have come up since, in part because he continues to throw more and more of himself into his work and give up less and less of himself everywhere else. Who is he? You have to look to the movies to find out.