Before he became a filmmaker, before he created what is widely considered the greatest baseball movie of them all, Ron Shelton toiled as an infielder in the minor leagues. He never made it to the majors, but he did observe and listen, and he learned to see something noble in the everyday hustle.

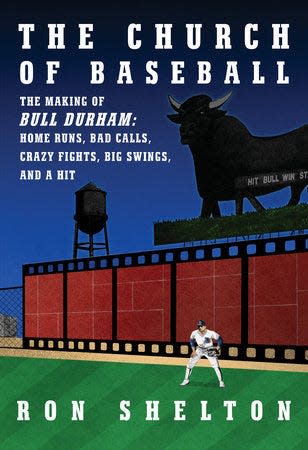

Around this time he picked up Jim Bouton’s book “Ball Four,” a very unromantic exposé of Major League Baseball. “I loved the Bouton book, but most players didn’t,” Shelton writes in his eminently readable book about his first and best movie, “The Church of Baseball: The Making of Bull Durham: Home Runs, Bad Calls, Crazy Fights, Big Swings, and a Hit” (Knopf, 256 pp., ★★★★ out of four, out Tuesday). “They saw it as a betrayal of the sanctity of the clubhouse. I saw it as humanizing all these athletes, who were much more compelling in their flaws and fears than the PR version foisted on the fans.”

Zachary Levi had a ‘breakdown.’ Here’s how ‘Radical Love’ helped him heal

Those flaws and fears, and their capacity for comedy, were what guided “Bull Durham,” much as they guide Shelton’s book. This is a down-and-dirty account of how the unlikely 1988 classic was conceived, made and sold, soup to nuts, from idealistic plans to corporate reality. Its ground-level tone and attention to detail strip away the romance of moviemaking, with only minimal rancor. In contemporary parlance, Shelton keeps it real.

Shelton’s elevator pitch for what became “Bull Durham” was “’Lysistrata’ in the minor leagues,” referring to Aristophanes’ play about women who withhold sexual favors from their war-mad husbands. He imagined a pitcher, a catcher, a woman and … not much else.

June’s top rom-coms: Jenny Colgan’s ‘An Island Wedding’ and Lucy Score’s ‘Maggie Moves On’

“The process of writing is also one of discovery,” Shelton writes. “Do I really want to know what it’s about on page one or would I (and ultimately the reader/viewer) be better served with discoveries along the way – mine and theirs?” He takes a similar approach to casting. “I want to be able to hand a part to the actor and tell them, ‘Up till now, I know more about this character than anyone. Now it’s yours – show me all the things I don’t know.’” He embraces the mystery.

Of course, Shelton got his screenplay written and his movie cast. Not that it was easy. One prominent suit wanted Anthony Michael Hall in the Tim Robbins role of pitcher Ebby Calvin “Nuke” LaLoosh. Fortunately Hall showed up to his meeting having not read the script, and Shelton was within his rights to tell him to take a hike.

Other studio operatives thought Susan Sarandon looked horrible in the dailies; Shelton correctly told them they were nuts. Even Kevin Costner, on his way to becoming a bona fide movie star, had his detractors. As Shelton points out, sometimes the suits just want their pound of flesh. He ultimately had to fire the movie’s original cinematographer, Charles Minsky (whose work Shelton loved), to save Robbins’ job. That’s the kind of bargain that makes sense only in Hollywood.

The end result was a movie that found rough magic and big laughs in the details: a meeting on the pitcher’s mound, a seduction set to the poetry of Walt Whitman, a sad, poetic monologue on the difference between hitting .250 and .300.

There’s no treacle in “Bull Durham,” or in Shelton’s book. Bouton would be proud.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: ‘Bull Durham’ book on movie, why studio didn’t like Susan Sarandon