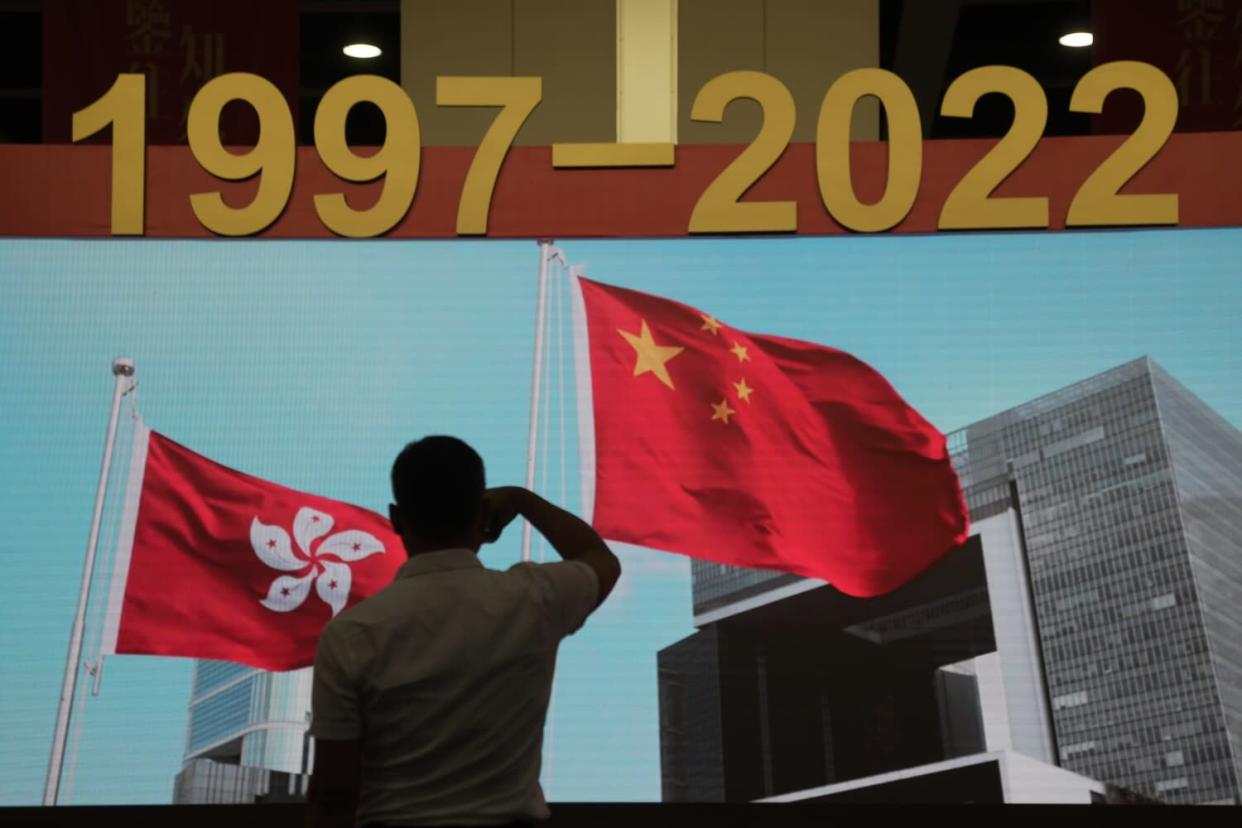

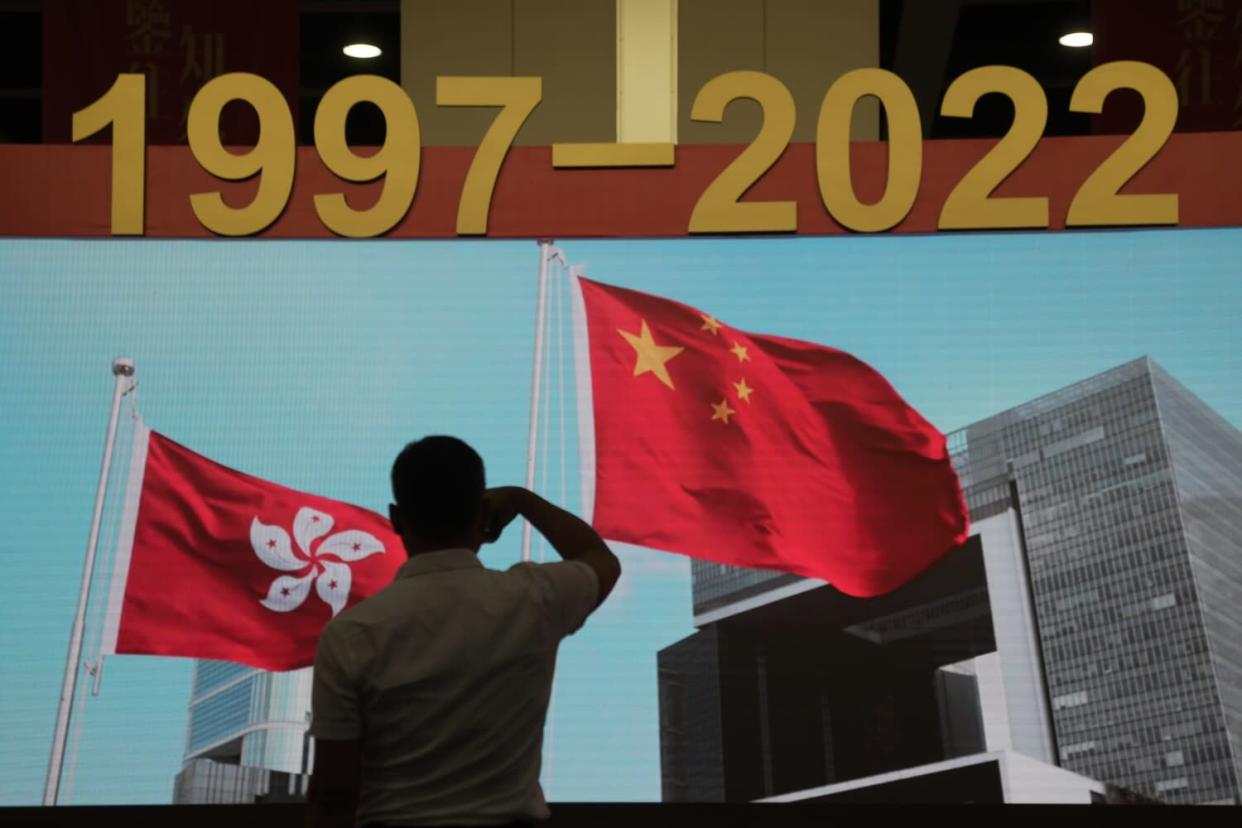

Even before he set foot in Hong Kong, Chinese President Xi Jinping’s intent was clear: to usher in the city’s next chapter under the firm grip of Communist Party rule.

In his first trip out of the mainland since the pandemic began, Xi arrived in Hong Kong on Thursday afternoon to commemorate the 25th anniversary of its handover from Britain and to attend the swearing-in of incoming Chief Executive John Lee on Friday. Xi’s presence amounted to a declaration of confidence in the city’s stability after years of COVID-19, political protests and a subsequent crackdown on dissent.

It was also a moment for Xi to further cement his position as China’s most powerful leader since Mao Zedong, months before he is expected to break with the norms of the post-Mao era and secure a third term as president. Many believe he will not stop there.

Stepping off the high-speed train at Hong Kong’s West Kowloon station, Xi and his wife were greeted by officials and masked schoolchildren who chanted warm welcomes and waved flowers and Chinese and Hong Kong flags.

As the couple made their way across the winding red carpet to a marching band’s tune, other attendees held up long red banners hailing their arrival and swayed under lion dance costumes. Around the station, anniversary decorations proclaimed: “A new era. Stability. Prosperity. Opportunity.”

“The symbolism says a lot,” said Minxin Pei, a professor of government at Claremont McKenna College. “This is an opportunity to show that he’s in charge.”

The Chinese leader has returned to a vastly different Hong Kong compared with his last time in the city five years ago. In 2019, the city was rocked by widespread protests over a bill that would expand Beijing’s legal jurisdiction in the former British colony. Then COVID-19 broke out, restricting travel and gatherings. As contentious clashes between police and protesters dwindled, Beijing implemented a national security law that saw hundreds of protesters, journalists, politicians and jailed, while others fled abroad.

The measures have effectively hastened Hong Kong’s 50-year transition to complete Chinese rule, a period during which the city was meant to retain a high level of autonomy and democratic freedom under the “one country, two systems” model formulated by the late Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping. In a short speech upon arrival, Xi declared Hong Kong a testament to the principle’s success.

“Hong Kong has withstood test after rigorous test, prevailing over every risk and challenge,” he said. “After this experience, Hong Kong rises from the ashes, showing vigor and vitality. … As long as we unwaveringly uphold ‘one country, two systems,’ Hong Kong will surely have an even brighter future.”

But critics inside and outside the city argue the opposite, saying that “one country, two systems” has essentially been jettisoned by Beijing, despite its signed agreement with Britain.

“Hong Kong is now for all intents and purposes just another Chinese city,” Pei said.

This year is of extreme political importance to Xi, whom China’s National Party Congress is expected to grant another presidential term in the fall. By quelling the unrest in Hong Kong and installing an unequivocally pro-Beijing regime, he has made strides in one of his key priorities: the reunification of the Chinese “motherland” and territories it considers its own.

That also includes Taiwan, another target of Deng’s split-rule model. Xi has called more forcefully for reunification with the self-governed island, even though its ruling political party, along with a majority of Taiwanese citizens, oppose unification and mainland aggression, leading to increased cross-strait frictions and concerns that Beijing may try to achieve its goal militarily.

“Beijing’s presence in Hong Kong will only reinforce those views in Taiwan,” said Ja Ian Chong, associate professor of political science at the National University of Singapore. “Beijing can make promises, such as allowing Hong Kong to have its own system and democracy, but ultimately is quite ready to take them away.”

The U.S. and Britain have criticized China’s repression of democracy, free speech and civil liberties in Hong Kong following the national security law, accusations that the current Hong Kong government rejects as “unfounded” and foreign interference in internal affairs. Washington has imposed sanctions on dozens of Hong Kong officials, including the new chief executive, Lee, and his predecessor, Carrie Lam.

The soured relationships between China and Western democracies have suffered further from China’s implicit backing of Russia in its invasion of Ukraine. At a NATO summit underway in Madrid, the alliance is set to modify its strategic concept to address China for the first time, labeling Beijing a “strategic challenge” and raising concerns over its political and economic ambitions and policies.

Despite Xi’s declaration of confidence in Hong Kong’s future, the extreme measures in place for his visit indicate lingering fears of further political or pandemic disruption.

Two high-ranking Hong Kong officials tested positive for the coronavirus in the days before Xi’s arrival, reinforcing concerns over infection risks. Thousands of residents are undergoing quarantine in order to participate in the week’s festivities, according to the South China Morning Post.

Authorities are also leaving little to chance when it comes to potential shows of political opposition. The city has deployed thousands of police officers for the events, banned the use of drones and made several arrests for alleged acts of sedition, according to local media.

While Chinese state media confirmed Xi’s planned visit this week, further details, even for attendees, have been scarce under the tightly controlled and coordinated agenda. The Foreign Correspondents Club in Hong Kong said this week that at least 10 journalists with local and foreign media were rejected from covering the events for “security reasons,” while some media outlets were not able to apply for accreditation at all.

Even with all the precautions, Xi will likely shuttle back to Shenzhen, on the mainland across from Hong Kong, to stay there Thursday night before returning to Hong Kong again Friday, the South China Morning Post reported.

“That shows that the officials are not fully confident that everything is under control in Hong Kong,” said Ho-Fung Hung, a professor of political economy at Johns Hopkins University.

Through arrest sweeps, a purge of “unpatriotic” politicians and the dismantling of independent media, substantive opposition to Hong Kong’s new leadership has been all but stamped out. However, Lee and Xi must still confront the city’s economic future, which has taken a deep hit from China’s strict zero-COVID protocols.

At the same time, residents and companies have begun to leave amid political turmoil and the pandemic, igniting concerns about a brain drain and threatening Hong Kong’s status as a major international business and finance hub.

In a poll conducted by the Chinese University of Hong Kong last year, 57.5% of respondents between ages 15 to 30 wanted to leave the city, up from 46.8% in 2018. The American Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong said in its latest annual survey that, because of pandemic restrictions, 26% of businesses were more likely to leave, while 44% of respondents said they personally were eying the exits.

Xi has said Hong Kong’s challenges can be overcome, with the strong backing of mainland support. Recently, he stressed the importance of Hong Kong’s steady development and engagement with young people, as well as the territory’s economic and industrial integration with the mainland through neighboring Guangdong province.

“The big challenge now will be to revive the economy,” Hung said. “They want to show that they have the determination to do it, but there is no easy way to guarantee to the world that Hong Kong is still good for business.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.