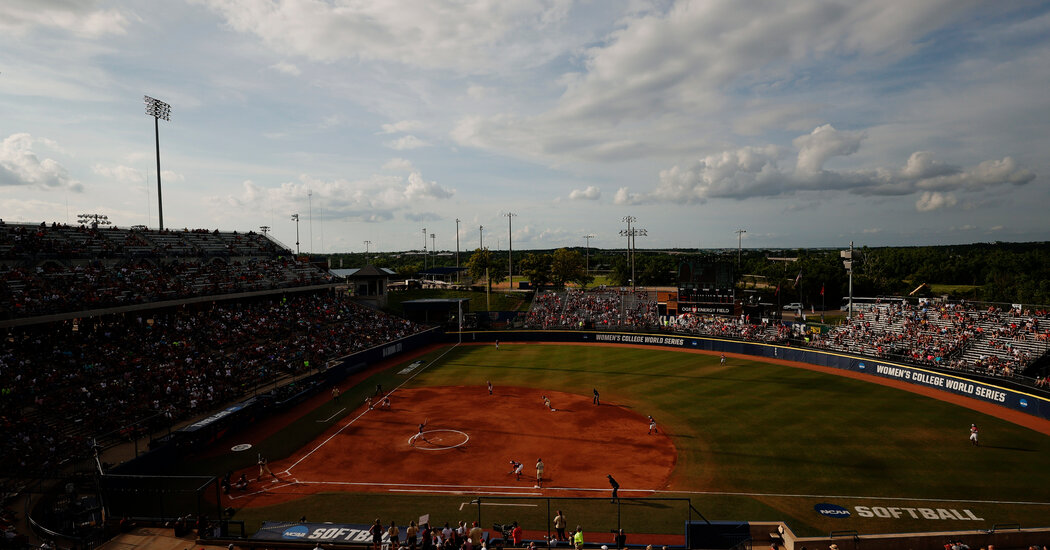

OKLAHOMA CITY — Last Saturday, like many days here in early June, was a softball fiesta. The 13,100-seat stadium — burnished and bulked up by a $27.5 million renovation that added a second deck — was teeming with young pony-tailed fans from Alva to Ardmore, partisans in Oklahoma, Oklahoma State or Texas colors, and softball aficionados who make the yearly sojourn to the Women’s College World Series.

The scene was an apt representation of the sport’s growth. Just a generation ago, most seating at USA Softball Hall of Fame Stadium was on grass berms and a few rows of temporary outfield bleachers. Now, the membership of the American Softball Association, whose headquarters are on the grounds, has ballooned to more than two million people. On television, ratings for college softball continue to blossom.

But the deepening roots of Division I softball’s championship tournament, which has been played almost exclusively at this site since 1990, and the state of Oklahoma’s standing as the epicenter of the sport may soon be tested by an unlikely foe: politics over abortion rights.

That could have a widespread effect on college athletics — potentially sidetracking the careers of athletes who are prohibited from having an abortion legally, influencing where athletes choose to attend school, and exposing some coaches, trainers and administrators to lawsuits for helping any athlete get an abortion.

The repercussions may be felt most acutely in Oklahoma, where Gov. Kevin Stitt last month signed a measure to prohibit nearly all abortions starting at fertilization, and allow private individuals to sue anyone who “aids or abets” an abortion.

The abortion law, along with another recent Oklahoma statute barring transgender women from playing on women’s sports teams, represents a new test for the N.C.A.A., which has used championships to take stands on issues that affect college athletes.

The N.C.A.A. moved a 2017 men’s basketball regional out of North Carolina after the state enacted a law barring transgender women from using women’s bathrooms. The state, which lost that year’s N.B.A. All-Star Game, eventually passed a replacement bill that removed enough of the troubling language from the law for the N.C.A.A. to return to the state for high-profile events.

In 2020, the N.C.A.A. pressured Mississippi lawmakers to remove Confederate imagery from its flag, threatening to withhold any championship events from the state.

The issue of abortion may be more vexing for the N.C.A.A. given the divisions in the country and among those in the world of college sports. The question of the Women’s College World Series has percolated in the halls of the N.C.A.A.’s offices in Indianapolis, but several committees that study women’s athletics, inclusion and mental health are unlikely to formally consider the implications of changing abortion laws until their next meetings in the fall, at the earliest.

Last summer, the N.C.A.A. agreed to consider equity and inclusion as it evaluates future championships.

N.C.A.A. leaders are waiting to see if athletes press them on abortion the same way they have with issues of mental health and racism, according to two N.C.A.A. officials, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to discuss the subject publicly.

The N.C.A.A. declined to make any officials available for this article.

Moving the softball championships would be painful.

The stakes over a softball showdown would be significant, both for Oklahoma City, which estimates that the Division I tournament pumps more than $20 million into the city’s economy, and for the N.C.A.A., whose leaders are weary from a string of recent court and political battles that have hurt the reputation of a multibillion-dollar industry that insists its athletes not be considered employees.

Any move by the N.C.A.A. to move the tournament from Oklahoma would surely be difficult, and it is unlikely that other events that are coming up would be moved, like next year’s men’s basketball Final Four in Houston and the women’s basketball Final Four in Dallas, both in Texas, which has an anti-abortion law nearly as strict as Oklahoma’s.

A relocation because of abortion laws would certainly be greeted by opposition from some N.C.A.A. member schools, especially faith-based universities like Baylor, Brigham Young and Liberty. And some large state universities would likely be skittish about crossing state legislators who control their budgets.

Some prominent college basketball players, including Stanford’s Cameron Brink and Oregon’s Sedona Prince, were among 500 current and former high school, college and professional athletes who last year signed an amicus brief supporting abortion rights in the case before the Supreme Court, including about a dozen women who had played softball in college.

The brief, which was also signed by the U.S. Soccer star Megan Rapinoe and the W.N.B.A. player Diana Taurasi, argued that a woman’s ability to make decisions about her own body supported the success of the United States women at the Tokyo Olympics last year, where women won nearly 60 percent of the nation’s 113 medals.

“Women’s participation in athletics would suffer, including because some women athletes would not be able to compete at the same level — or at all — without access to abortion care,” the brief asserted, citing several statements from former Olympic athletes who said their careers would have been derailed if they had been unable to have an abortion.

Still, pressure on the N.C.A.A. from college athletes has not yet materialized.

Part of that could be timing. The Supreme Court draft opinion was leaked at a time when academic calendars were winding down and when athletes who were in season — including softball players — were sharply focused on winning championships. Just like across the American public, views among athletes and others within college sports about abortion are nuanced.

“I’ll say that our team does have the important conversations, and we also do a very good job of compartmentalizing,” said Megan Faraimo, a star pitcher for U.C.L.A., a school whose rich vein of athlete activism has been reactivated during the pandemic. Close to half the Bruins softball team took a knee before the national anthem last week, a common sight in college sports the past two years.

“When we’re on the field, we’re playing ball,” Faraimo continued. “I think that’s the beautiful part about this sport. We’re more than athletes; we’re going to have those conversations. But we’re also going to play out.”

The issue is not academic for women’s athletes.

Victoria Jackson, a former collegiate distance runner who is a sports historian at Arizona State, said such conversations are essential.

When the N.C.A.A. in 2001 prohibited championship events from being held in South Carolina because of the state’s refusal to remove the Confederate flag from the statehouse — a ban that lasted nearly 15 years — it meant moving the regional cross country championships out of Greenville, S.C., where they had been regularly held.

“Every team had to talk about why they weren’t going to Furman,” Jackson said, referring to the college that hosted the event. “I do feel like there must be a conversation around the softball championships about what to do.”

Among younger athletes, she added: “There’s been a generational loss of how important the right to choose to have an abortion or not is, and how intimately it is tied to sports. Women are returning from pregnancy now, but that’s a recent phenomenon.”

According to the New England Journal of Medicine, unplanned pregnancies in 2011 were highest among women aged 20-24 (81 per 1,000 women); 42 percent of unintended pregnancies ended in abortion. There is no available data on unplanned pregnancies among college athletes.

In 2017, Sanya Richards-Ross, an Olympic medal-winning sprinter, revealed in a book that she’d had an abortion to compete in the 2008 Games. “I literally don’t know another female track athlete who hasn’t had an abortion,” she said.

How Roe v. Wade’s repeal might impact female college athletes was a topic that few participants in the softball World Series were interested in discussing.

U.C.L.A.’s Kelly Inouye-Perez, the only one among the eight head coaches in Oklahoma City who agreed to an interview, did not directly address the topic, but she invoked Title IX, which included greatly expanding women’s access to college sports. She said “opportunity means choice” across a variety of circumstances.

“I’m encouraging my female student-athletes to have the strength and courage to take a stance, but do your homework,” Inouye-Perez said. “Make sure you’re not just following what everybody is doing, but do your homework. See how it’s impacting you.”

Coaches at Arizona, Texas, Florida, Northwestern and Oregon State declined interview requests, and the coaches at Oklahoma and Oklahoma State, after initially agreeing to interviews, later declined.

Asked at a Saturday news conference what she would tell the parents of recruits who were concerned about the state’s anti-abortion law, Oklahoma Coach Patty Gasso said: “I don’t feel equipped to answer that because it’s never come across. I don’t even know how I would go about it. I just don’t feel comfortable on this stage to be talking about those subjects, to be honest.”

Gasso, by far the nation’s highest-paid softball coach at more than $1.1 million this season, answered a question last month about Oklahoma’s restrictions on transgender athletes similarly. Gasso told the university’s student newspaper, the OU Daily: “I haven’t been really in research mode, but I will learn more as we go along.”

A patchwork of laws would raise ‘tough questions’ for athletes.

These are subjects upon which Gasso, whose team won its sixth national championship on Thursday by sweeping a best-of-three series from Texas, may have to get up to speed.

Gasso, who came to Oklahoma from Long Beach (Calif.) City College in 1995, recruits heavily in her home state. Four starters are from Southern California, including the team’s star freshman, Tiare Jennings, who is from San Pedro and hit two home runs on Wednesday.

Jennings’s mother, Maria, said her daughter was so happy in Oklahoma that she may never come home, but she said that anti-abortion bills would raise “tough questions” for recruits in California.

The State of Roe v. Wade

What is Roe v. Wade? Roe v. Wade is a landmark Supreme court decision that legalized abortion across the United States. The 7-2 ruling was announced on Jan. 22, 1973. Justice Harry A. Blackmun, a modest Midwestern Republican and a defender of the right to abortion, wrote the majority opinion.

Heidi Supple, whose daughter Sydney is a junior at Northwestern University in Illinois, said she “absolutely” viewed abortion rights as a gender-equity issue and would not feel comfortable if her daughter attended school in a state that restricted them. “I think for a lot of young women that will be a compelling factor,” said Heidi Supple, who is from Oshkosh, Wis.

Kelli Braitsch starred on Oklahoma’s first national championship team in 2000. And last Saturday she sat in the first row behind the first-base dugout with her wife, cheering on the Sooners.

The government, she said, has no more business governing her body than it does restricting gay marriage or transgender rights. “For women, it’s everything we fight for,” she said.

She also remembers one of her former college teammates who had an abortion. “She would have lost her scholarship if she hadn’t, so she made a choice,” Braitsch said. “She got her degree and has had a nice career, but what would have happened if she didn’t have that choice?”

Dot Richardson has seen up close how an unplanned pregnancy can challenge a young athlete’s plans.

Richardson, who helped U.C.L.A. to its first national title in 1982, won a gold medal for the United States before completing medical school. She recently finished her ninth season as the coach at Liberty, the religious school founded by the Rev. Jerry Falwell, who died in 2007. Sex outside of marriage is a violation of the school’s honor code.

Richardson said she has had two players become pregnant, and neither had an abortion.

“One of our girls, the guy sent her $650 to get an abortion,” Richardson said. “If her teammates didn’t come to me and say, ‘Coach, we don’t know what to do?’ I don’t know what would have happened.” Richardson recalled with a smile telephoning the pregnant player’s father and telling him: “I don’t know how to tell you this, but you’re going to be a grandpa.”

“My biggest message is we can do more — more education, more support,” she added. “How do we help young women with their choices?”

The N.C.A.A. has shifted — and so have athletes.

Two years ago, Oklahoma was among the hubs where college athletes were making their voices heard after the murder of George Floyd. Oklahoma State’s star running back, Chuba Hubbard, publicly scolded his coach, Mike Gundy, when a photo surfaced of Gundy wearing a T-shirt promoting a right-wing TV network. And among the Oklahoma athletes raising their voices was Ashlynn Dunbar, a volleyball and basketball player who took to social media to tell fans not to cheer for her if they did not support her right to speak out.

Much has changed since then.

Consider that around the same time, N.C.A.A. President Mark Emmert emphasized in an interview with The New York Times that his organization would not dodge political subjects if they negatively affected athlete welfare. “When there are issues that affect students, under my leadership I’m not going to hesitate to encourage that we do take those positions,” he said, shortly after the N.C.A.A. had been among those that nudged Mississippi lawmakers to remove Confederate symbols from the state flag.

Now, though, Emmert is a lame duck after agreeing to leave his post by this time next year in part because he had become a political liability for the N.C.A.A. Adding to the uncertainty, a new, far smaller Board of Governors — reduced to nine members from 21 — will be seated in August when the N.C.A.A.’s new, streamlined constitution takes effect.

“The N.C.A.A. is not a political action committee,” said Betsy Mitchell, the athletic director at Caltech and a former Olympic swimmer who is a member of the N.C.A.A. committee on women’s athletics, one of four boards dedicated to issues of inclusion.

She continued: “You could make the case on some other issues around supporting young people: Oh, you can’t host the championship if you’re going to be anti-trans or actively trying to hurt trans people. But my personal opinion is that it isn’t an appropriate use of our energy or time — not because I don’t care or support the chilling effect of repealing Roe v. Wade. I just don’t think the N.C.A.A. should be taking up these kinds of topics.”

And yet Mitchell’s committee last year supported the N.C.A.A.’s statement that it should create a formal process for evaluating championships through an equity lens. Mitchell was asked if she considered abortion a gender-equity issue. “Wow,” she said, pausing for a moment to think. “I don’t know. I certainly see it as a human rights issue or a civil rights issue.”

Last Saturday night, after the USA Softball Hall of Fame Stadium had emptied out, the discomfort with speaking about changes in abortion law and the implications for college sports was evident.

Chyenne Factor, a senior outfielder for Oklahoma State, was asked at a news conference: Did she think athletes who had raised their voices on mental health and social injustice matters recently might do so again about abortion laws?

Kenny Gajewski, Factor’s coach, intercepted the question.

“I don’t know that this is the time and place to be talking about some of this stuff,” he said. “These kids are here to play softball and represent their schools.”

Gajewski then said that student welfare should be given greater sway, and went on to use an example about a random late-night drug test putting undue stress on his starting pitcher.

Gajewski was asked if he was suggesting that Factor, 23, a three-time conference All-Academic player, could not play softball and have thoughts on abortion laws at the same time.

“Your assumption is wrong on that,” Gajewski said, pausing just long enough for the moderator to intercede.

“That’s enough,” said the news conference moderator, Roger McAfee, an assistant athletic director at Cleveland State. “Any other questions for the student-athletes?”

Alan Blinder contributed reporting; Kitty Bennett contributed research.