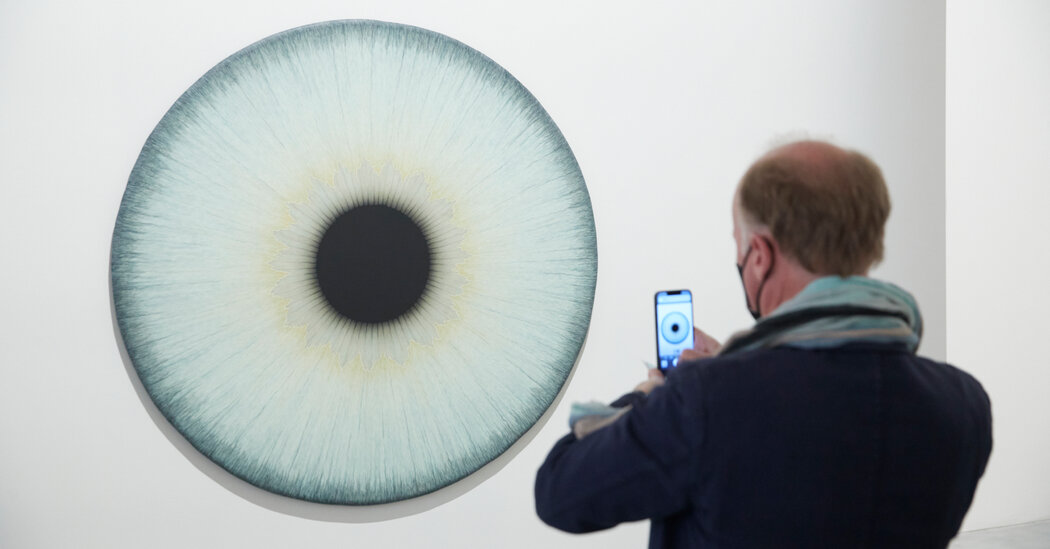

VENICE — It starts in the eyes: shy or seductive, gaping or sealed shut, aqueous frontiers between the mind and the world. There are the pupils of the German surrealist Unica Zürn, cohering out of dense, automatic black squiggles. The giant irises of Ulla Wiggen, each unique as a fingerprint and capable of unlocking a credit card or blocking passage across a border, painted in close-up on circular canvases. All over town, on palazzo-side posters and the hulls of the vaporetti, there are eyes announcing the 59th Venice Biennale: ghostly, milky corneas, drawn by the young Mexican artist Felipe Baeza, disembodied, floating in deep space.

It’s a commonplace (and one you won’t catch me using) to call an art exhibition, especially one as large as Venice’s, a “feast for the eyes.” The 2022 Biennale, or at least its central exhibition, is a feast of the eyes: a giant, high-spirited banquet of looking and scrutinizing. Eyes emerge as the key metaphor of a show that’s all about bridging realms — the brain and the social network, the dream and the ecosystem. The eyes here in Venice are portals to the unconscious but also analyzers of misrule. They stare out from paintings, bulge from videos, and on occasion (as in Simone Leigh’s bronze totem “Brick House”) clamp closed. We may be on display, but we are looking back, or looking inward.

This year’s edition of the world’s oldest and most important contemporary art exhibition has been organized with triumphant precision by the New York-based Italian curator Cecilia Alemani, who’s mounted a major show in challenging circumstances: canceled studio visits, choked shipping routes, galloping insurance costs and, now, a land war 900 miles from the lagoon. Alemani’s exhibition, titled “The Milk of Dreams,” was meant to open in May 2021. The coronavirus pandemic pushed both this show and Venice’s architecture biennial back a year, and she’s made very good use of the delay.

Her challenges were not only logistical. For a while I’ve felt that biennial exhibitions of contemporary art may have run their course. No coherent new style or movement will be emerging from our perpetually imitative present, and if you visit this year’s largely appalling national pavilions (the other half of the Venice Biennale, over which Alemani has no control), you’ll see what slim pickings contemporary art is offering up. So the curator and her team used their extra year to dip into the archives — in 2020 Alemani co-curated an exhibition on the Biennale’s first 100 years — and established a 20th-century lineage, notably through Surrealist and feminist traditions, for the themes of this show.

One of these Surrealist and feminist themes is that bodies and technologies can’t be cleanly cleaved apart. Nature and society are always reshaping each other — more than ever in time of climate crisis — and in this show machines act like animals, bodies twitch like robots, flesh merges with prostheses, and metals and plastics keep drooping, leaking, melting.

Another theme is a reenchantment of our spiritless world to arrest the political and ecological crises that empire and patriarchy have reportedly consigned to us. If modern life stripped the divinity out of Venice’s altarpieces, and made art appreciation a secular enterprise, this show wants to turn the gondola back around. So prepare for a biennial chockablock with spirits and shamans, mutations and metamorphoses, where the world we live in — for better, for worse; in beauty and in kitsch — regularly takes a back seat to worlds beyond.

Junkies of recent continental and feminist philosophy will recognize the mood music: Rosi Braidotti’s theories of the posthuman, Silvia Federici’s analyses of witch-hunting as gendered violence. And yet: When too many biennials let the labels do the theoretical heavy lifting, Alemani’s selections are strongly opinionated and deftly chosen (though not without following some recent fashions: Indigenous cosmologies; weaving as metaphor for computer algorithm; two whole rooms filled with piles of dirt). They include participants from all over, notably Latin America, and never decline into the tokenism that afflicts so many European and American museums.

The show is heavy on painting — return of the repressed, baby! — and, despite its posthuman inquiries, light on new media. It has frequent surprises and moments of stunning bad taste, such as a sculptural suite by Raphaela Vogel of a cancerous penis on wheels paraded by 10 cadaverous white giraffes. (You read that right.)

All this without mentioning what, from a less subtle curator, would be the headline here: this is the largest Biennale since 2005, and some 90 percent of its artists are women. Just 21 of the 213 participants are men, and all are showing in the Arsenale, Venice’s former shipyard; in the classical galleries of the Giardini, the number of men is exactly zero. Elsewhere around Venice it’s still the old game, with concurrent exhibitions of Anselm Kiefer, Georg Baselitz, Kehinde Wiley and other bombastic boys.

This Biennale would have been a failure if reversing the old gender bias were its mere endpoint. For Alemani, the exhibition’s disproportion has a much more precise aim: reconstituting the past to let us see the present with keener eyes. She pulls this off primarily in five shows-within-the-show — historical parentheses that frame her contemporary selections, each set off from the main flow via colored walls of dusty pink or robin’s egg blue. (The exhibition design this year is by the young Italian firm Formafantasma, who’ve subdivided and tamed the Arsenale’s tricky wide spaces.)

In the mustard gallery of the mini-show “The Witch’s Cradle,” we meet women artists who used masquerades or fantasias to evade or deconstruct male stereotypes. They include the renowned Surrealists Leonora Carrington, Dorothea Tanning, Leonor Fini and Meret Oppenheim; Italians such as Benedetta, who redeployed Futurist drawing to new subconscious ends; and also many Black American women, including Josephine Baker, Augusta Savage and Laura Wheeler Waring, the last of whom drew Egyptian/Art Deco covers for W.E.B. Du Bois’s journal The Crisis. This metaphysical tradition gets picked up today by the Portuguese-British pastelist Paula Rego, who emerges as a star of this Biennale with an entire gallery of her fraught scenes of domestic violence, where love and fear make humans act like dogs.

A second, delightful mini-show presents women artists who examined the topologies of vessels, bags, shells and containers: a beaded purse by Sophie Taueber-Arp, hanging nets by Ruth Asawa, punctured white plaster ellipses by Mária Bartuszová (eyes, eyes, eyes), and incredible papier-mâché models of the pregnant human uterus by Aletta Jacobs, a pioneering 19th-century Dutch doctor. (Let me add that, in literal terms, this is the deadest biennial I’ve ever seen, with just under half the participants in the grave.) The contemporary Thai artist Pinaree Sanpitak, who paints hazy shapes that might be leaves, or breasts, or tear ducts, offers a beautiful contemporary exploration of forms with indistinct interiors and exteriors.

Prosthetics — human inventions that make human boundaries indistinct — are a related leitmotif. I found myself engrossed here in the life of Anna Coleman Ladd (1878-1939), an American sculptor who used her classical training to craft gelatinous facial protheses, of latex and painted metal, for maimed World War I veterans. That intertwining of flesh and technology ripples through the sculptural works in the show: whether Hannah Levy’s drooping silicone on spidery metal legs, Julia Phillips’s bronze armature supporting a cast of an absent female body, or Tishan Hsu’s resin hybrids of faces and phone screens. These are among the show’s best works, though I wish Alemani had gone all the way and included Matthew Barney: master sculptor of prosthetic-grade plastics, whose attention to permeable bodies and fluid identities prefigures almost all this show’s obsessions.

Then there’s the automatic drawing and writing, séances, spiritual channeling. We have the Victorian mystic Georgiana Houghton communicating with the dead through tangled watercolors; the dense symmetrical fantasies of Minnie Evans, in which human eyes gaze out from butterfly wings. Mediums and faith healers. Spiraling vines, blossoming flowers. This all gets picked up, among contemporary artists, by Emma Talbot’s sentimental painting on fabric of starbursts and babies in amniotic fluid, Firelei Báez’s rebarbative murals of DayGlo Afrofuturist deities, or else beaded flags depicting animal-human hybrids by the Haitian artist Myrlande Constant. I clocked at least three artists drawing vines and tendrils sprouting from nipples or genitalia.

How much you can tolerate all this will depend on your own particular attunement to the music of the spheres. For my own disenchanted part (and especially as war rages), I have serious misgivings about the escapism of this magical thinking, as if, with just a little more respect for the divine feminine, everything will be all right. You can’t take a break from modernity, not even in your dreams — a lesson underscored in this Biennale by the quick-witted Inuk artist Shuvinai Ashoona, who draws seals, whales and octopuses in the drab apartment blocks and municipal buildings of the contemporary Indigenous Arctic. And the most compelling projects in “The Milk of Dreams” delve right into the incompleteness and instability of the modern world, rather than trying to get back to the garden.

In the Giardini, Alemani has choreographed a brilliant succession of five galleries that turn to gender and computing technologies, and how art might reveal our algorithms’ powers and misapplications. They begin with Wiggen’s new large irises, as well as strange and fascinating paintings she made in the 1960s of networked circuits and motherboards. (The word “computer,” after all, referred initially to predominantly female clerical laborers.) Next we encounter Italian female Op artists — Nanda Vigo, Grazia Varisco and four others — who put rational forms to eye-bending ends.

After them come two incisive women who reformatted drawing and painting for the computer age. One is Vera Molnár, who in the 1970s “drew” minimal compositions by outputting code to an early computer plotter (and who’s still working from a Paris nursing home at 98). The other is Jacqueline Humphries, whose dense abstractions of halftone dots and emoticons reaffirm painting as an ideal medium of digital perception.

One of the art world’s favorite recent catchphrases is “alternative knowledge,” cribbed from anthropology and misapplied to just about anything that defies rational expectations. A dream may be beautiful, a dream may be powerful, but a dream is no kind of knowledge at all. A better sort of “alternative knowledge” is the knowledge imparted by art, at least at its most ambitious: the pulse-racing insight into our human condition we suddenly perceive when forms exceed themselves and feel like truth. The best artists in this determined, imbalanced, and properly historic Biennale look right at that human condition, with unclouded eyes.

59th Venice Biennale: The Milk of Dreams

Through Nov. 27; labiennale.org.