10 years ago, Disney’s “John Carter” opened nationwide.

Meant to be a potential franchise-starting blockbuster, it was savaged by critics, who called the film “wanly plodding and routine” (Entertainment Weekly), and “a giant, suffocating doughy feast of boredom” (The Guardian), and was met with indifference by general audiences, who simply didn’t show up. (It opened in second place, behind forgotten animated Dr. Seuss adaptation “The Lorax”).

Quickly, the movie and its fate took on a nearly mythical dimension – it wasn’t just a box office disappointment, it was a staggering creative and commercial failure, the kind of movie that is often mentioned in the same breath as other high-profile misfires like “Ishtar” or “Waterworld.”

But the actual story of “John Carter” – how it was conceived, what happened during production, and how it all fell apart thanks largely to a misguided marketing campaign – is much more complex and much more interesting.

Most Hollywood bombs are perceivable early on, through a toxic combination of untested filmmakers, iffy (or unfinished) screenplays and unfortunate miscasting, leading to a troubled production that eventually equals an underwhelming film. In the 2006 documentary “Boffo! Tinseltown’s Bombs and Blockbusters,” Morgan Freeman equates the making of a cinematic debacle to an airline crash: “It’s usually caused by a series of mishaps.”

“John Carter” had none of these elements. There were no true mishaps. It was based on a beloved and highly influential property, created by craftspeople at the top of their game, led by a director whose previous films were runaway successes. The simple, sought-after narrative of “what went wrong” quickly falls apart. Or is at the very least obscured. And because of that, it makes telling the story of what happened much more complicated.

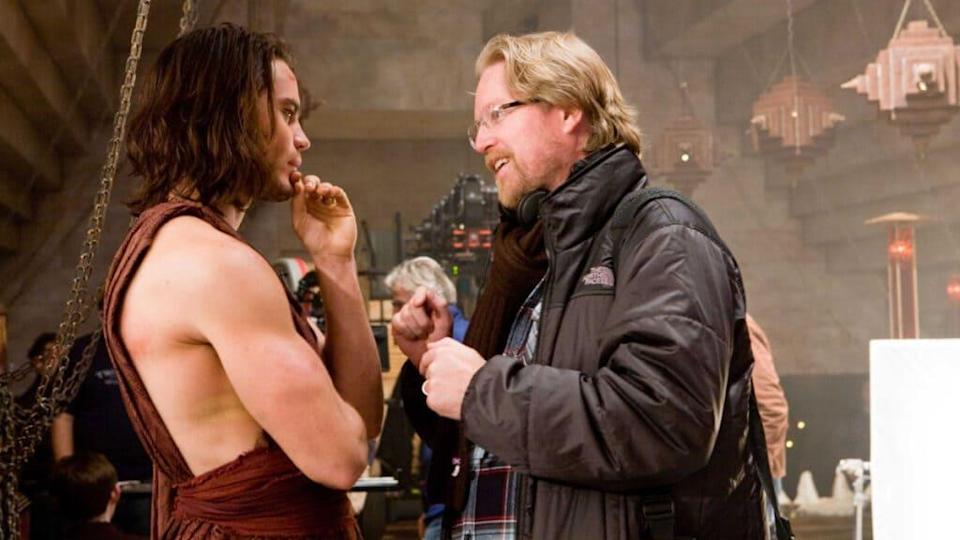

TheWrap talked to a half-dozen creative principals involved with “John Carter” for this story, conducting exclusive interviews with co-writer/director Andrew Stanton, writer Michael Chabon, cinematographer Dan Mindel, and performers Willem Dafoe and the Princess of Mars herself, Lynn Collins. (Disney was unable to accommodate TheWrap’s request for additional interviews with personnel still at Pixar.)

What emerges is a story of a filmmaker making the uneasy transition from animation to live-action, an unorthodox shooting schedule that left some cast members lost, a flawed and confounding marketing campaign, and how shifting corporate allegiances and mandates left a $307 million adventure, meant to start a franchise and based on beloved source material essentially marooned.

In the Beginning…

“John Carter” is based on the first Edgar Rice Burroughs Mars novel, “A Princess of Mars,” published in 1917. Originally released in a serialized format in a pulpy magazine called “The All-Story” with the title “Under the Moons of Mars,” the story was divided into six monthly installments and published from February to July 1912. American author Burroughs, a noted fantasist and the creator of “Tarzan,” envisioned a Martian landscape teeming with strange creatures, where warring factions battled for the planet’s resources and a former Confederate soldier was spirited away by forces he couldn’t possibly understand. Readers were immediately hooked by the imaginative concept and Burroughs’ prose, where he gave Mars a new name – Barsoom.

Ten more books followed, and the stories would serve as the inspiration for some of the most iconic sci-fi of all time — from “Star Wars” to “Dune.”

As early as 1931, attempts were underway to turn the Burroughs Mars books into features. “Looney Tunes” director Bob Clampett first approached Burroughs about translating the property into an animated feature. Test footage was produced in 1936 but failed to impress exhibitors, whose support he desperately needed. Had the exhibitors been properly wowed, there’s a possibility that Clampett’s “A Princess of Mars,” and not Walt Disney’s “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” would have been the first feature-length animated film.

While stop-motion animation pioneer Ray Harryhausen expressed interest in the property sometime in the 1950s (Burroughs died in 1950), the next legitimate crack at the material came in the late 1980s, this time via Disney. Producers Mario Kassar and Andrew G. Vajna, who specialized in high-concept, big budget extravaganzas, had secured the rights with Jeffrey Katzenberg, an executive who had recently been installed by Michael Eisner and Frank Wells. At the time studio badly needed a live-action hit, especially one that could spawn a lengthy and lucrative franchise. Various screenwriters were assigned to the project in the late 1980s, including Charles Pogue (David Cronenberg’s “The Fly”) and Terry Black. “They want this to be the next ‘Star Wars,’” Black told the Los Angeles Times in 1988. After Black, the young screenwriting duo of Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio (who would eventually write “Aladdin” and “Pirates of the Caribbean”) were handed the project.

By 1990, filmmaker John McTiernan, who was coming off the unparalleled triple-play of “Predator,” “Die Hard,” and “The Hunt for Red October,” became attached to direct. He hired “Back to the Future” screenwriter Bob Gale, whose take on the material offered more humor and incorporated elements from several earlier drafts. McTiernan also hired William Stout, an illustrator and concept artist who at the time was working on various projects for Imagineering, the secretive arm of the company responsible for the theme parks. By 1992, McTiernan had installed Sam Resnick, a writer the director had worked with (and liked) on a TV movie version of “Robin Hood.” Around that time Tom Cruise became loosely attached to the project as Carter, with Julia Roberts approached to play the Princess of Mars, Dejah Thoris.

As development continued, McTiernan became increasingly dissatisfied with the limitations of technology. He was convinced that computer-generated imagery was the only way to go, and this was still a year before “Jurassic Park” had opened. Stout recalled designing elaborate costumes for animals to wear; his enthusiasm waned too. Finally, McTiernan left the project to direct “Last Action Hero,” which was ultimately clobbered at the box office by “Jurassic Park” and labeled one of the biggest disasters in cinema history, just as “John Carter” would be all those years later.

A Director Shuffle

In 1994 Kassar and Vajna’s company Cinergi went bankrupt, following the similarly disastrous opening of “Cutthroat Island” (another one for the box office bomb hall of fame). For a decade the rights to the property languished, until producer James Jacks and Austin, Texas-based blogger Harry Knowles pursued the property for Paramount. They ended up in a bidding war, with Paramount hiring Mark Protosevich (who eventually worked on “Thor”) to write the screenplay and attaching “Desperado” director Robert Rodriguez, who planned to use an all-digital filmmaking technique to bring Frank Frazetta’s memorable cover artwork to life.

It sounded like a grand slam, but Rodriguez had resigned from the DGA following disagreements over his adaptation of Frank Miller’s “Sin City” (it’s conceivable that, had his version of “A Princess of Mars” gone through, Frazetta would have been given a similar co-director credit). Paramount, unwilling to bankroll a non-union project, quietly let Rodriguez go. With Rodriguez gone, Paramount hired Kerry Conran, who had just directed the buzzy “Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow” (which shares certain tonal and aesthetic similarities to the “Mars “stories) and screenwriter Ehren Kruger.

By 2005, Conran and Kruger had left and Jon Favreau and screenwriter Mark Fergus had been brought on. The Favreau/Fergus version was ambitious – it was said to incorporate elements from the first three novels (“A Princess of Mars,” “The Gods of Mars,” and “The Warlords of Mars”) and use a combination of practical make-up effects and computer-generated imagery to faithfully capture Burroughs’ stories. When this “John Carter of Mars” stalled, Favreau and Fegus moved onto an equally ambitious project based on a property just as revered and adored (and one that had been through a similarly tumultuous development process) – Marvel’s “Iron Man.”

Enter Andrew Stanton. Stanton had been a fan of the John Carter property since Marvel had released a comic book adaptation, “John Carter, Warlord of Mars,” that ran from June 1977 to October 1979. In high school he read the collected paperbacks. “My friends that were female would jokingly call them my romance novels and say, ‘You’re still reading your romance novels right now?’” Stanton said.

When Stanton joined Pixar in 1990, he was the second animator hired and its ninth employee. (Pete Docter was its third animator.) At the time it was a computer animation division spun off of George Lucas’ Industrial Light & Magic and purchased by former Apple head Steve Jobs, in part to build powerful graphics computers. As time went on the emphasis shifted more and more to its computer animation business. Stanton went on to co-write “Toy Story” (when the production hit story snags, it was Stanton who was locked away in a “small, windowless room,” churning out new pages, according to David Price’s “The Pixar Touch”), “Monsters, Inc.” and “Toy Story 2.” He eventually wrote and directed “Finding Nemo” (at the time the biggest animated movie ever) and “WALL•E,” rapturously reviewed by the same publications that would later annihilate “John Carter.”

It was during the prolonged production of “WALL•E” that Stanton started to dream of other worlds. “You spend so long on an animated movie, it takes five to four years, depending on how long the story takes to break. And by the time we’re actually making it or shooting it, you kind of can see the future of it and your mind starts to wonder creatively about what you want to do next,” Stanton told TheWrap. “I was like, What do I want to do next? And I was kind of dry, as far as an animated idea. I felt like I was crazy. I never had that problem before.”

Stanton had been following the various iterations of “John Carter” for years. “That’s something I have spent my whole life wishing somebody would make, and when I was in the industry from maybe the ’90s on, if I ever heard even the slightest rumor it might get made, I would get all excited like a fanboy and go, I’ll be the first in line to go and see it,” Stanton said. “I never had the hubris to think that’s something I would want to do or could do.” But when the Favreau iteration fell apart, something stirred inside him. “It was one of those kismet moments where I’m like, It’s so crazy, it just might work, you know?”

Disney didn’t own the rights yet. But Stanton went to the top brass and made, as he says, “an impassioned plea.”

“I had nothing to lose because it wasn’t like I had to do this in the sense of I have no career or that I needed the next paycheck or something like that,” Stanton said. Instead, he told the execs, “I think these things are about to fall into public domain and I think you could reinterpret them to be something that could be digested today.” Stanton was envisioning a classic tale for modern audiences. “I remember saying, ‘Fine if I don’t make it, but you should be the ones making it,’” Stanton said. “And I meant it. I thought it had the potential to just be a big franchise.”

Pre-“Game of Thrones” and the streaming boom, Stanton saw the saga of John Carter as an ongoing, episodic, big-screen adventure. “I always thought of it just like the paperback books. Those books came out way before any of us were born, before even our parents were born. When we were introduced to them, it’s like kids now are introduced to all the ‘Harry Potter’ books now. They came out and there were 12 books. It just existed as this long story,” Stanton said. “And so I was like, ‘This needs to be seen as something that keeps going.’”

But who would help bring John Carter to the big screen? And how would they do it?

Assembling the Team

As in the story of “John Carter,” let us take a moment to flashback to an earlier time: the mid-1990s. That’s when Michael Chabon, years before he won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, also had Mars on his mind. He completed a screenplay called “The Martian Agent.”

“It was, if I do say so myself, a little ahead of its time because it was steampunk at a time when that term was not widely in use at all. It was about the conquest of the planet Mars in the 1890s by the British Empire,” Chabon said. “Having completed their conquest of Earth, they had discovered the secret of interstellar, interplanetary flight in a very 1890s kind of way and were embarked on the conquest of Mars.”

Chabon now describes it as a “hodgepodge” of the John Carter stories, which he had loved since he was 10 years old. Jan de Bont, the former cinematographer who, if “John Carter” had been made by John McTiernan in 1990 probably would have shot it, was brought on to direct. De Bont was coming off of the back-to-back success of “Speed” and “Twister.” He had visual flair and could handle complicated visual effects. De Bont was in the middle of making “Speed 2” as pre-production work continued on “The Martian Agent.” Chabon and de Bont worked on the script, while Industrial Light & Magic worked on the visual effects. Derek Thompson was one of the ILM animators who, like Chabon, loved the Carter stories. They discussed their mutual admiration for the stories during meetings.

“They spent about a million dollars at the time on special effects tests for the movie. Then ‘Speed 2’ came out and there went Jan de Bont,” Chabon said. “It just fell apart. It didn’t go forward after that.” (Chabon later turned part of the script into a prose short story that was included in “McSweeney’s Mammoth Treasury of Thrilling Tales,” released in 2003.)

By Chabon’s estimation, a decade had passed. He was at a Christmas party at Brad Bird’s house. Bird, an accomplished animator who had worked at Pixar on “Ratatouille” and “The Incredibles,” is a friend of Chabon’s. And who does he run into at the party? Derek Thompson, late of ILM and now at Pixar.

“He came up to me at this party and reintroduced himself. We chatted and talked about ‘The Martian Agent.’ He said, ‘Well, have you heard the news? Disney has acquired the rights to John Carter. They’re going to let Andrew Stanton going to direct it. He’s doing the movie. It’s going to be live action.’ I said, ‘Oh my God, that’s so exciting.’ We talked about that for a little bit,” Chabon said. “That was a Friday. On a Monday, I got an email from Andrew Stanton who’s saying, ‘Hey, I heard that you worked on this Mars project, and we’re doing John Carter. Would you like to see what we’re up to?’ I said, ‘Of course.’”

Chabon visited the pre-production offices, just down the street from Pixar in a place appropriately called Fantasy Studios. Chabon saw what Stanton and the pre-production team were up to and looked at artwork that had been amassed. “Then at the end of it, he just turned to me in the car and he said, ‘So you want go to Mars?’ That was it. That’s how I came on board,” Chabon said. At the time Stanton had a draft done with Mark Andrews, another Pixar vet. “That’s the point at which I came on and stayed on all the way through,” Chabon said.

“I already knew they were both were secret lovers of the same band, is the way I put it. We all have the same albums and we all kind of, ‘Oh, you listen to them too?’” Stanton said of Chabon and Andrews. “We had the same boyhood love of Carter. It was like a pinch-me moment of, Wow, if I could work with those two, I know that it would be made with nothing but love. And that’s pretty much how it felt.”

With Chabon on board, Stanton rounded out his other Martian agents – Nathan Crowley, who had worked on Christopher Nolan’s “Batman Begins” and “The Dark Knight,” would be responsible for the production design; composer (and Pixar vet) Michael Giacchino would be tasked with giving John Carter an appropriately heroic theme; and cinematographer Dan Mindel, who had recently shot J.J. Abrams’ blustery “Star Trek” reboot,” would photograph the sands of Mars.

Mindel had small children and admitted to having seen every Pixar movie “about five million times each.” According to him, “John Carter” was pitched as the first live-action Pixar film. “It felt, to me, that it was just going to be the most incredible opportunity to see how that company works and how those guys do stuff,” Mindel said. “I was really excited to do that.”

Unlike Favreau, who wanted to base the look of version on Frank Frazetta’s illustrations (arguably one of the more iconic and memorable iterations of the characters), Stanton went in a different direction. “I think at the time, even then, I was like, ‘It’s very sexist and it’s very male, fanboy dominated.’ And I just didn’t see the need for that. I think you can find the individuals just as attractive and a different definition of sexy or romantic without having to be naked and gratuitous and this Frazetta look,” Stanton said. “I wasn’t anti in the sense that… I was just as much as a fan as a kid. But I’d just grown up, and I wanted these people to be real. I want anything, whether it’s a fish or a robot or a toy or a human being, I want them to be seen as dimensional as possible and be seen as somebody with thoughts and opinions and surprise in how they may react to something, and contradictions. And you try to get as much complexity as you can with these things. And I was really big on that with the alien creatures. I wanted them to seem like nature could have produced them under different circumstances even on our planet.” Not that the final product is completely free of Frazetta influences, as Chabon points out. “I think you could actually argue there’s a lot of the costume and spectacle of it that is not unreminiscent of some Frazetta imagery,” Chabon said.

There was also the matter of casting “John Carter.”

When I asked Stanton if there was a unifying philosophy he went into casting the movie with, he said no (besides, of course, casting British actors as many of the villains, a “very ‘Star Wars’” move). “I think because I knew that the cast was going to grow with creatures and it was going to grow with different types of races if we were to continue. And it was going to get a little more fantastical,” Stanton said. “I just think at the time, even now, it’s a big ask to suddenly make everybody literally have ‘Star Trek’ green skin. It’s just a tough one to make palatable. I just decided it wasn’t worth going there.”

Then there was John Carter himself. Stanton admits that “the lead role was a tough one to pin down. We saw everybody.” While he wouldn’t name who else auditioned, he said, “it’s literally a shorter list of who we didn’t see.” An actor quickly emerged as a frontrunner – Taylor Kitsch, star of the television series “Friday Night Lights.” (Kitsch declined to talk to us for this story, which is frankly understandable.)

Carter, as a character, is tough. He’s a widower whose wife and child were killed, and he’s a veteran of the Civil War – as a Confederate. (One of the characters describes Carter as, “Every inch a cavalry man.” Early concept art saw him wearing a low-slung hat emblazoned with the Confederate flag.) “I wanted to not absolve him of that, but also not make him pro the side he was on. The best I could do was neutralize him,” Stanton said. “And just make him disillusioned by everything he had chosen to do, war in general, let alone the wrong side. And so that was conscious at the time.” Chabon said the lack of properly grappling with Carter’s confederate ties was ultimately a “compromise.” In the final film, Carter comes across like Kurt Russell’s Jack Burton in “Big Trouble in Little Child,” a gruff everyman annoyed by the overtly fantastical situation he’s in.

And while Stanton was determined to cast Kitsch, he and his producers still continued to consider other actors for the part. One of the actors in the running for this new version of John Carter was a performer familiar with the property – Tom Cruise.

Cruise unexpectedly reemerged, hungry for the role he was once set to play. According to someone close to the production, Cruise actively campaigned for the job. Stanton admitted that there were “discussions,” but he largely didn’t budge. Kitsch was his guy. “I had Taylor already in mind by the time Tom made his interest known. Tom had a long history with the material, so it wasn’t too surprising to discover he still had interest in it. He was a consummate professional in his discussions with me about the role, and beyond respectful to the fact I was already on an audition path with Taylor,” Stanton said. “We agreed to talk further if I were to pass on Taylor, but I obviously didn’t. It was as simple and non-controversial as that.”

Lynn Collins, who was eventually cast as the Princess of Mars, Dejah Thoris, remembered Cruise’s attempts too. “That’s a different story entirely because he may have thought he was in the mix, and I think him and Andrew had some conversations, but I don’t think he was ever actually in the mix so to speak,” Collins said. “I mean the people who were testing were the people that they were considering and they were all 20 years younger than him basically is what I’m trying to say. I mean, it may have been a desire. I don’t know how practical that desire was.” At the very least, it’s fascinating to think about whether a Cruise-led “John Carter” would have had a different trajectory (and it’s also fascinating to note the year after the release of “John Carter,” Cruise starred in two sci-fi projects: “Oblivion” and “Edge of Tomorrow”).

While Collins never tested with Cruise, she did screen test with actors like Josh Duhamel, who had co-starred in the “Transformers” franchise, and her old buddy from “X-Men Origins: Wolverine,” Kitsch. (Stanton said it was down to five actors, and a handful of actresses, including Collins, when the winnowing process began.) The scene that served as the chemistry test was one where Dejah slaps John Carter across the face. “Basically I was just doing a scene where I kind of got to beat these guys up,” Collins said. When she performed with Kitsch, it was clear that they had something special. “Taylor and I have always had incredible chemistry. It was inevitable that we would get a chance to really explore it and work as a team,” Collins said. “The other guys were amazing and I’m sure the other actresses were amazing too, but that’s what these chemistry reads are about – what are all these people like together?”

Collins, who knew of the characters thanks to her father’s love of Edgar Rice Burroughs, remembers Kitsch walking into her trailer after the screen test. She was smoking at the time. He said that if she gets this role, she has to stop smoking. “I was like, ‘Yes, if I get the job, I’ll stop smoking,’” Collins said. She got the role and kept her promise.

Other actors might have auditioned, Cruise might have lobbied hard, but for Stanton it was always going to be Kitsch. “I had always had Kitsch in mind from the minute I saw ‘Friday Night Lights.’ I saw him, I think it’s the pilot, and he’s ticked off the boss and he’s left out on the rain in the mud and the bus drives off with him. It became this iconic imagery for ads for the show,” Stanton said. “And I remember thinking, I feel like I’ve seen that image before.” As it turns out that image – Kitsch soggy and sullen – perfectly matched a cover of “A Princess of Mars” that Stanton owned. “I had nothing to do with the movie at that time. It was just this removed thing. But then by the time I was thinking [about casting], I never forgot that I had always thought of that,” Stanton said. “He just kept fitting the bill from the first meet to the audition, to the screen test. It just kind of became obvious to us once we saw Taylor fully dressed and on screen and against Lynn that that was it.”

Part of the casting of Kitsch and Collins was Stanton imagining the actors being able to grow along with the parts as the franchise progressed. This was, after all, imagined as a grand trilogy. “I was always thinking of a story that kept going. And it would take a while to make these three movies. I’m like, How do I feel about how these people might age in the next five to seven years?” Stanton said. “And so that was all part of the consideration.”

Beyond Collins and Kitsch, Stanton continued to populate his cast amazingly well. Yes, there are the British performers who co-starred as villains or more morally nebulous roles, people like Dominic West (as a warrior of a warring city) and Mark Strong (as an immortal being), and even more colorful performers dot the periphery – Bryan Cranston plays a Union soldier on Earth who tries to recruit Carter to his cause and Willem Dafoe and Samantha Morton, arguably two of the most magnetic cast members, are completely unrecognizable since they performed in motion-capture suits, transformed in post-production into members of an alien race known as Tharks.

Dafoe had worked with Stanton before on “Finding Nemo,” and adored their creative partnership and described it as a “wonderful time.” “That’s a particular kind of performing, but it showed how imaginative he was, how tenacious he was, and how I like being in the room with him,” Dafoe said. “Then on top of that, Pixar was such an incredible place, because they were smart, they devoted so much time to research and development, and they really reworked things. There was nothing cynical about their approach. They were very on it. They were always testing things. They were always bouncing ideas back and forth. It wasn’t just about making a product. It was really about exploring possibilities. That’s the guy that asks me to play this 12-foot-tall Jeddak of this green race of Tharks. What? You’re going to say no to that? I don’t think so.”

Roll Cameras

Production on “John Carter of Mars” (as it was then known) began in early 2010 at Longcross Studios, outside of London. A giant ramble of drafty buildings, Longcross was formerly used by the Military Vehicles and Engineering Establishment to build tanks for use during World War II. And while the production didn’t start with any major hiccups, the early adoption of soundstages over on-location photography was a red flag (like the kind billowing on a Zodangan airship), at least for cinematographer Mindel.

“I remember meeting them all at Disney very early on and the way the script was written it was set obviously in the only place on Earth that really looks like Mars which would be the Four Corners,” Mindel said, referring to a region of the southwestern United States where the southwestern corner of Colorado, southeastern corner of Utah, northeastern corner of Arizona, and northwestern corner of New Mexico all meet. “One assumed, as one always does, when you read a script like that, in the beginning that those locations were built into the DNA of the whole thing and were never ever going to be moved to some second rate studio complex in the United Kingdom to shoot. I think that was a huge error, trying to save a buck and put the movie in England when it should have been shot in the Four Corners. Every minute of it.”

While the production did eventually move to the Four Corners, according to Mindel, the damage had already been done. “A lot of the studio work that we had done was so compromised because of the choice of studio, the size of the stages, the fact that it was all inside when it should have been outside, all that kind of stuff,” Mindel said. “Ultimately your hands are tied when you’re in a flying ship that is supposed to be open to the elements flying through the air in broad daylight and you’re in a studio in the middle of winter in the UK. It’s impossible to make those things feel texturized and part of a real environment. I think that it really suffered for that.”

For Stanton, he was just trying to figure out how to operate in live action after spending so much time in animation. “It’s a little hard to put myself back there because it’s been 10 years and I’ve done a lot of television since then. And it’s all normalized, the ways that you work in live action. But the actual day-to-day and the terminologies and the methods that you use to get the same results are very opposite sometimes, where they’re directly opposing the other.”

Still, the shoot was a pleasure for Stanton, who says that he “loved it.” “I didn’t realize I was so spontaneity-starved after nearly 20 years of planning movies which is really the way it’s done at Pixar,” Stanton said. “Instead of having to compose for an orchestra that some day played the score I was writing, I was suddenly thrown into a jazz concert and having to improv right there with my sax.” Stanton described the shoot as “scary as all get-out but it was thrilling.” “I remember there would be many days where it was either that impossible to get the day done or that hard to shoot, or that hot, or that cold. And I would just tell myself my heroes did this. Lean did this, Spielberg did this. Everybody whose movies inspired me and that have informed my taste, had to do whatever this is I’m doing today.”

According to Collins, the London part of the shoot was difficult, “People got moody and we’re all away from our families.” But when they moved to Four Corners, everyone “had a blast.” Collins says that the location shoot was also the last time that she embodied Dejah as she was originally written, detailing changes that were requested for the eventual additional photography. “I think a lot of the things that the conflicts came in about were my character because she’s written in the original script, I slap him four or five times in the movie. I mean, she’s the princess of Mars. She’s like a warrior. And I think probably what ended up happening, and this is just speculation, but I’ve had a lot of time to do that,” Collins said. “I think ultimately Disney was like, she’s too strong. She comes off as a bitch. She comes off as too hard. You guys need to add scenes that soften her up and cut anything where she’s physically violent, basically, to John.” What makes this even funnier is that her chemistry read was one of the scenes where she slaps John.

Willem Dafoe had some experience with motion-capture prior to shooting “John Carter,” not that it prepared him for how physically demanding the role would be. “Not only was it mo-cap, it was a little more involved, because I was on these huge stilts. I also was wearing a camera on my head. Where the tusks were, there were little arms. The cameras were on the end of that, so they could capture my facial expressions. It was very involved and quite grueling physically. Five months on stilts was quite an achievement,” Dafoe said. “Particularly when you’re walking in desert sand and that sort of thing. That was a challenge, but it’s fun. It’s a game, it’s a new way of performing. Basically, you are creating material for them to shape the character, because you are being filmed, they aren’t just going to a computer, but you’re also making the performance very specific, because they’re getting all the information of your facial expression and of course your voice and your postures.”

For Mindel, he employed a more restrained aesthetic for “John Carter.” He had worked with Jackie Chan much earlier in his career on “Shanghai Noon,” and Chan advised him to keep filming even after the director yells cut, because that’s when magic will happen. “Andrew was so precise about where the cuts were going to go and what was going to happen that there was very little room for improvisation. Perhaps that is one of my motivations for keeping it fairly kind of restrained.”

Still, Mindel sought out the cinematographer role on “John Carter,” partially because he wanted to know how to make a movie that employed this much animation and visual effects. “This is the future and that’s kind of how I looked at ‘John Carter,’” Mindel said. “That it was going to be a massive learning curve on the edge of the technology and for me that was one of the sort of motivators to get involved.”

Roll Cameras… Again

Everyone we spoke to loved the actual shoot, and there weren’t any calamitous events that usually signal a problem movie – it didn’t go wildly over budget, there were no stunts that went awry, cast members didn’t walk out and production heads weren’t swapped. But there was an element of the production that raised eyebrows – the decision to essentially come back to do extensive additional photography more than a year later.

Nowadays this “additional photography” is built into every big budget film schedule; it has become a tenant on which the Marvel Studios movies are based (“Thor: Love and Thunder,” out this summer, is going back for additional photography in the next few weeks, for example). But at the time it was a signal of indecisiveness and potential trouble; that Stanton couldn’t hack it. Someone once told me they had shot the entire movie “at least twice.”

A famous Tad Friend-penned profile in the New Yorker, which inexplicably ran in the fall of 2011 and saw Friend visit the set in Playa del Vista during the additional photography, captured how tense the atmosphere already was, in terms of defining what they were shooting. “What I didn’t want to say is ‘We’re doing a reshoot,’” Collins told Friend. Kitsch chimed in: ““Or even ‘We’re doing a few pickup shots’—because they’ll f–king nail you, like the movie is doomed.” Ironically, if the narrative of “John Carter” is doomed took root anywhere, it was with the publication of this profile.

Stanton says that the structure of the shoot was there from the beginning. In his words, the additional photography was “part of the design.” “What I did when I pitched making the movie, and actually the logistics of making the movie, I said the only way we know how to make a movie at Pixar and the reason they’re so good is because we basically make the movie four to seven times. We don’t animate them; we save that till the end. But we board them, put our crappy voices to them and put CD soundtrack music to it. And we put on a play, like a bad dress rehearsal again and again and again and change whatever we do until it’s better,” Stanton said. “I’ve never been part of a movie where you make it once and it works. I literally remember saying, ‘If that’s what you demand of me, let’s not do this.’ I said, ‘Can we take part of the budget and upfront, already put on the map, on the calendar, we’re going to have this amount of time and money to finish either what we didn’t finish shooting on the first go round, or to correct what we got off on?’” Disney agreed. And Stanton did the additional photography.

For Collins, though, the additional photography was where she started to see the strength and determination of her character start to erode. They “added the scenes of her and her father.” She remembers Stanton and producer Lindsey Collins telling her, “I think they think that she’s too hard and they want her to be more likable.”

Collins was having trouble keeping track of which Dejah Thoris the filmmakers (and studio) wanted – the headstrong adventurer and warrior of Mars, or the more demure love interest for John Carter (they had also directed her to speak with a British accent). “Eventually, during the reshoots, I finally was just like, ‘Andrew, stand by the camera and tell me what to do.’ Just tell me what to do. Because I’ve lost track of who this is,” Collins said. “And he was like, ‘It’s you, basically it’s you.’ And I was like, ‘Great. Okay. So just tell me when it’s off, and if you need more of this or that.’ I just had to let go entirely.”

Stanton, Collins pointed out, was nothing but encouraging and helpful throughout the entire production process. “Andrew, in my opinion, in many ways can do no wrong,” Collins said. “He not only held my hand through the whole process, but he was just, it was so vulnerable to be like, okay, here I am. And my butt cheeks are out. I’m trying to have a six pack. And he was so supportive and so encouraging and so complimentary.” She remembers that she was going through some personal hardships during production too, of which Stanton was conscious and just as kind.

Chabon would send scenes to Stanton and get them back from him throughout pre-production and production. “I would send him a scene that he said needed something done to it. He would tinker with it and send it back to me and say, ‘This, but then do your thing to it.’ So, then I would do my thing to it,” Chabon said. “Then I’d send that back to him, down to the point where we’re dealing with a half a page scenes, just back and forth. It was really fun. It was a wonderful experience.”

Mindel said production was “a gift.” “I tried so hard to keep it in the sort of fantasy space that I thought it should be in. I’m proud of it. I think it’s good. I mean, there’s a few wonky pieces, obviously, but basically I love it,” Mindel said.

And the learning curve Stanton was going on, which was sometimes precipitous, finally ended with a true understanding of animation versus live-action. “I finally figured this out I think by the time I was done shooting on ‘Carter,’ which was that all the people that love reading the instructions went into animation, and all the people that hate reading instructions, stayed in live-action or went to live-action,” Stanton said.

While the shoot might have been over, the journey to Mars was far from complete. And team “John Carter” was about to experience some significant turbulence.

Losing Mars

Several significant developments unfolded while Stanton was still shooting “John Carter.”

In the summer of 2011, Lionsgate’s “Conan the Barbarian” was released. Like “John Carter,” it was the retelling of a beloved pulp hero, this one created by Robert E. Howard, and this new version carried a sizable budget ($90 million) and a cast that combined up-and-coming television stars (led by Jason Momoa) with more established names (like Stephen Lang). It also fell considerably short at the box office. After the opening, one of the screenwriters, Sean Hood, took to Quora, a kind of Ask Jeeves-style message board, and wrote about the experience.

“A movie’s opening day is analogous to a political election night. Although I’ve never worked in politics, I remember having similar feelings of disappointment and disillusionment when my candidate lost a presidential bid, so I imagine that working as a speechwriter or a fundraiser for the losing campaign would feel about the same as working on an unsuccessful film,” Hood said. He went on to talk about how passionate the fan base was, and how the character had endured after all these years. And yet it was a flop at the box office and critics hated it.

One of those reading that post was Michael Chabon.

“When I read that, just this chill just sent on me. Even though at that point, I don’t think I had any indications yet. Nothing had gone wrong that I was aware of at least,” Chabon said. “But still I was like, ‘Oh, f–k. That could happen to us.’ It hadn’t occurred to me before,” Chabon said. “I was like, ‘No. We’re doing something so great. It won’t happen to us.’”

Elsewhere, the Martian sand underneath the filmmakers’ feet was starting to shift.

Dick Cook was the studio chief who greenlit “John Carter.” He was replaced by Rich Ross, who came from the company’s television division. “All of these people were grappling with the fact of this movie that none of them understood, or cared about, or didn’t mean anything to them,” Chabon said. “They didn’t get anything about it, and they were now in charge of marketing this thing that they didn’t understand, love, care about, or know, and had no real emotional, or professional, or business stake in it because they weren’t the ones who had fought for the rights, and invested in and greenlighted the project.”

Also, unbeknownst to the production, by the summer of 2011 (when “John Carter” was entering its additional photography phase), Disney CEO Bob Iger had started discussions with George Lucas to purchase Lucasfilm — and by extension, “Star Wars.” While the deal wouldn’t be finalized until a few months after “John Carter’s” release (for a whopping $4 billion), the would-be franchise repeatedly pegged as the company’s answer to “Star Wars” since the late 1980s was now moot – they didn’t need their own “Star Wars” anymore. They were about to just straight-up own “Star Wars.”

Still, post-production trucked along.

A handful of visual effects companies were hired to handle the movie’s complex computer-generated imagery which included, amongst other things, a walking predator-city that was like a menacing version of a Hayao Miyazaki creation (many of the flying scenes bear a certain resemblance to Miyazaki works, including “Castle in the Sky” and “Porco Rosso”) and an adorable, dog-like creature named Woola who quickly becomes John Carter’s BFF. One of the visual effects houses the production leaned hardest on was Double Negative (now known as DNEG), at the time best known for their work on several Christopher Nolan films.

Robyn Luckham was an animation lead at the time and is now Animation Director and Global Head of Animation, DNEG. At the time he was coming off of having spent seven years in New Zealand. Having just completed work on “Avatar,” he was anxious to come back to England. “There was so much great creature work, performance capture, Andrew Stanton…” Luckham said. “It was a match made in heaven for us.”

Luckham said that there are two real types of animation in movies – there’s feature animation, like the kind of animation that Pixar produces, and there’s VFX animation, which Double Negative was responsible for. Stanton married the two disciplines. Luckham and his team learned a lot from the filmmaker. “He really wanted to talk directly to the animator on the shot, which is quite unique. You have to go through many layers of VFX supervisors to get your chance, but Andrew wanted to and everyone embraced it, and he was great. He started to teach us lots of things about what they do at Pixar and what we could do in our world, things like, he should be able to read the dialogue without any audio. So, when you are playing it back, you should know exactly what’s going on without the audio.”

One of the biggest challenges for the visual effects artists, including Luckham, was a sequence with hundreds of Tharks, the 12-foot-tall creatures (Willem Dafoe plays one of them) riding their beasts to the city of Zodanga. “It killed me. I remember doing it, but they wrote software just so we could handle the size of things. I’m like, There’s no way I can stop things intersecting. it’s impossible. There’s so many legs and there’s so thick. I’m like, you’re just going to have to be blurred and hope for the best that no one notices. No one did, thankfully,” Luckham said. “I remember the Thark stuff was super challenging. I’d open my work scene and it might take three hours just to get it open. I’m like, ‘Okay, let’s try and manage how to actually move something in this thing.’”

Even for Stanton, the amount of effects were daunting. “We were basically making two movies. So much of it was visual effects, it was basically making two thirds live-action and one third an animated movie, full on,” Stanton said. “There were more animated shots in what was left to do on Carter than an entire animated feature.”

Stanton also wrestled with the shape of “John Carter” in post-production, particularly with its controversial framing device, which has Carter’s nephew Edgar Rice Burroughs (Daryl Sabara) receiving a telegram that his uncle has died, after which he’s whisked away to his office and finds a hidden manuscript detailing his adventures on Barsoom. “There was always suggestions that were attractive, the idea of just starting with a guy waking up on Mars. And I always understood, and even in private sometimes you’d think like, Well, that would certainly grab me even more and get me going,” Stanton said. “But every time we tried it, both in script form and even in a couple storyboard forms before we’d shoot, the movie would just come to a grinding halt because at some point, you had to know all this other stuff that we would have.”

As Stanton and his collaborators struggled to finish the movie, work began on selling the movie. One of the biggest decisions came in the first part of 2011, when the project formerly known as “John Carter of Mars” simply became “John Carter.”

There was already some controversy around the title – “John Carter of Mars” is actually name of the final book in the Burroughs cycle. The first book and the one that the movie is based on is called “A Princess of Mars.” (“Technically the first movie should have been titled the ‘Princess of Mars,’ so off the bat, I was so confused as to what was happening,” Lynn Collins said.) “A Princess of Mars” was out of the question because, as Stanton said at a press event in December 2011, “I’d already changed it from ‘A Princess Of Mars‘ to ‘John Carter of Mars.’ I don’t like to get fixated on it, but I changed ‘Princess Of Mars’… because not a single boy would go.”

The decision to drop the “of Mars” was a little more complicated. Chabon remembers attending a meeting led by Disney’s new president of movie marketing MT Carney, who a New York Times article described as having “zero movie experience, coming from a New York marketing agency specializing in packaged goods.” She went through a list of 11 movies from the past 15 that all had “Mars” in the title – Disney’s own “Mission to Mars” and “Mars Needs Moms” (both costly duds), along with other movies like “Mars Attacks.” Chabon said that these were “movies that had in some cases had nothing in common with each other except for the fact that they have Mars in the title. Almost all of them were bad movies.”

“So, we’re taking Mars out of title,” Carney told the group. “It’s just going to be called ‘John Carter.’”

“That was first moment, I was like, ‘Oh, f–k. This is not good. We may be in trouble here,’” Chabon said. “From that meeting until it came out, it was not good after that.”

When speaking with Stanton, he was more diplomatic. “It wasn’t my call,” Stanton said matter-of-factly of the title change. “It was suggested and I didn’t fight it.” When pressed about Carney, he said that she “was clear and confident in her views on directions we should take.”

Somewhat confusingly, they allowed Stanton to keep the “JCM” logo on posters and other marketing materials. And the end of the movie, a second title card appears on the screen, reading “John Carter of Mars.” At the time Stanton told Badass Digest that he fought for the title card at the end of the movie, “Because it means something by the end of the movie, and if there are more movies I want that to be what you remember.”

The first “John Carter” teaser trailer debuted online on July 14, 2011. Set to a moody Peter Gabriel version of Arcade Fire’s “My Body Is a Cage” (Gabriel sang the closing credits song for “WALL•E”), the teaser eschewed any information about the collective accomplishments of the artists behind the movie (no mention of Stanton or Burroughs or Chabon), or the long legacy and impact of the Carter stories on popular culture. Considering the original stories informed everything from “Star Wars” to “Dune” to “Avatar,” it was quite an omission. Vulture later said that the movie was “doomed by its first trailer.”

There were reports, at the time, that Stanton did have enough finished effects shots to put in the trailer, perhaps owing to his inexperience with live-action (a claim repeated in the aforementioned Vulture article). The filmmaker refutes this. “Frankly, that kind of critique happens on every trailer,” Stanton said. “You never have the shots that the people want for your trailer.” It was also insinuated that Stanton was a little too involved with directing the movie’s marketing campaign. “I was very involved. And that might’ve been part of the problem. I don’t know. You can Monday morning quarterback this ’till you’re blue in the face. But I’m just as guilty for thinking maybe taking Mars off and putting it on at the end of the movie and just earning the right to have Mars for the rest of the series was a bad call. Who knows? I just don’t. In all honesty, there’s no upside to going back and trying to guess all the things that might’ve corrected something.”

In the weeks leading up to the release, there were still more baffling decisions – for every great idea, like Stanton hosting a TED Talk about the art of storytelling (a genuinely illuminating discussion), there was a very bad idea, like a global contest called “Are you the real John Carter?” where if your name was John Carter, you could win the chance to go to a secret fan screening of the film (this is 100% true). After a somehow even-more-befuddling Super Bowl spot (this one set to Led Zeppelin’s “Kashmir”), fans from TheJohnCarterFiles.com got together online to make their own trailer, one that acknowledged the legacy of the filmmakers and the property’s past. If Disney wasn’t going to sell “John Carter” properly, they would.

[embedded content]

All the usual levers that Disney pulls on their big tentpole releases and corporate priorities – a flood of merchandise in the retail and online stores (as well as big box locations like Target), targeted placement in the domestic Disney theme parks, primetime specials on the Disney Channel or ABC that could explore the history of the characters – were missing. The film was being zapped into theaters without any of the pomp and circumstance that usually accompanied a big Disney release.

A Disastrous Release

On February 22, 2012, the premiere of “John Carter” was held at Regal’s LA Live Theatre in downtown Los Angeles. This was somewhat odd, given that since Disney purchased and renovated the El Capitan in Hollywood, most of their premieres have been held there (starting with 1991’s decidedly “John Carter”-ish “The Rocketeer”). An official Disney press release trumpeted that the premiere “was held in a 800+ seat venue, in 3D for VIP guests, filmmakers, and studio executives on Regal’s huge 70-foot-wide screen. Simultaneously, two additional theaters were filled with D23 members. fans and radio ticket winners.”

Before the event, Stanton said that he was blissfully unaware of the bad buzz that had been patiently building. “I was, I think, a little deaf, dumb and blind to it all. I didn’t see it coming at all,” Stanton said. “I think what happened was everybody that did gave me a wide birth. I was left in my echo chamber and it was hard. It was really hard.” Mindel also said that he wasn’t aware of the storm clouds brewing over Barsoom. “I wasn’t very cognizant of any of it,” Mindel said. Collins too said that she was kept out of the line of fire. “They sheltered me, sheltered me, sheltered me until the LA premiere,” Collins said.

Dafoe had been following the press surrounding the movie and knew that the sentiment wasn’t good. “I mean, not obsessively, but, when you make something and you had a good experience and it was exciting, you hope that’s going to be conveyed and people are going to respond to it. I think it goes without saying that, and this is tricky because you don’t want to be, I don’t know — my recollection was that even before it was released, there were grumblings about it,” Dafoe said. “I heard what some of the grumblings were about, everything from the name change to regime change to poor publicity. But I remember before the movie was even seen, people were counting it out.”

“I remember the day of the premiere in LA. I was down with my family. We’re all staying in this hotel downtown, across the street from the theater where it was going to be premiering,” Chabon said. “We had advanced reviews, and they have all that advanced information they’re getting about ticket sales and all the algorithmic things they’re using to predict what the box office is going to be. None of it was good. You’re in that mode where you’re like, Well, they can be wrong. Those things aren’t always right. People are trading their counter examples they’ve heard of about one time when that stuff proved to be wrong. We just all kind of knew at that point it was going to be bad. It was not going to go well.”

Collins remembered walking the red carpet, with Kitsch walking in front of her. She saw Kitsch walking towards Rich Ross, who then told Kitsch something. Collins couldn’t hear it over the din of the red carpet (paparazzi and reporters shouting, fans screaming, publicists whispering into your hear). “He said something to Taylor and Taylor kind of took a step back and started to walk away,” Collins said. “And then I stopped and I was like, ‘What just happened?’ And he said, ‘It’s a disaster.’ He just told me, ‘It’s going to be a f–king disaster.’ And we still had to go down the press line.”

Things, incredibly, got even worse for Collins.

The night after the LA premiere, Collins and her then-partner were at another function for the film. Her then-manager turned to her and said, “You’re just going to have to disappear because you’re the one who’s going to get the heat for this.” Collins asked, “Why?” And her manager said, “This is just the way the cookie crumbles. Usually that’s what happens.” She called the period immediately after the film’s release “devastating.”

“It was so indicative of that stereotypical, the woman gets the brunt. Like really sh–ty,” Collins said. “Taylor went on to continue to work, he did ‘Battleship’ and other things, but basically my people shelved me for a while. This is so devastating because it wasn’t just the film disappointing me, now it was the entire industry and my representation. And I ended up firing those people. It took like a year for me to do that, but I took a break and tried to figure out, up until then my career and my work, I really allowed it to define me.”

Mindel basically wouldn’t talk to us about the release, saying, “That is a really dangerous conversation, I think, to have, while all the people are still alive.” Fair enough!

And the movie was a disappointment. It opened at the domestic box office behind “The Lorax” and wound up making only $281 million worldwide, which wouldn’t be that bad but the movie’s production budget (before tax rebates but also before marketing costs) was a whopping $307 million. Ten days after its release, Disney announced that it would take a $200 million write-down on the movie. Ross and Carney both left the studio almost immediately afterwards (Carney still had more than four years left on her contract). Perhaps they were sacrificial lambs on some alter on Barsoom. Or perhaps it was their comeuppance for not helping the film succeed.

Luckham said that Double Negative was even impacted following the film’s release. “It was tough for the company actually,” Luckham said. “They were trying to build this big creature department and go real full on, which they didn’t go so much. They went more back to what they knew. They had obviously done really well from it. But all that creature work that we wanted to do, everyone got cold feet because ‘John Carter’ didn’t have a good reaction. We didn’t have another big show like that for a long time. It was tough.”

Articles were feverishly written about what went wrong and what the approach should have been. Few discussed what went right. “John Carter” is a flawed movie, but it’s also endlessly charming. It has a winsome, earnest spirit and the action sequences bristle with ingenuity and life. It’s goofy, but it’s also incredibly fun, and harkens back to previous adventuresome live-action Disney movies like “The Rocketeer” and “Dick Tracy,” both costly productions that underperformed and both (now) cult favorites. The design and the cinematography are genuinely stunning and Stanton takes big swings, like a scene of Carter massacring a race of evil Tharnks that is intercut with him burying his wife and child back on Earth. The movie really goes for it in a way that few blockbusters do. Stanton left it all on the field.

A few months after its release, the Los Angeles Times did a piece checking in on Stanton. Immediately after “John Carter” came out, Stanton “escaped to New York and spent the next three weeks riding the subway, noodling on scripts and visiting with his daughter and some friends.” “I had to go into true ‘Lost Weekend’ to just purge myself. There’s always a little bit of hubris that has to come into just having the gumption to make something so big,” Stanton said. “There was probably a small part of that or maybe a big part of that that was healthy to just come back to Earth. And know that the sun was still going to rise and that it didn’t have to be everything about my life.”

Stanton got moral support from an unlikely source – Bob Iger. “He called me immediately and gave me a great quote that I think it’s the quote, you can look it up, about Teddy Roosevelt being the lonely man in the ring that has the guts to actually do it versus talk about doing it,” Stanton said.

The speech is called “The Man in the Arena,” it reads in part: “It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.”

“It was the best thing anybody could say at that moment and especially him. And I was just super grateful to him. I was grateful to him prior. I thought he was a great leader and a great guy coming into the company,” Stanton said. “It just made me all the more loyal to him after that, whatever they needed help with.”

Of course, what they really needed was a sequel to “Finding Nemo.”

Just a few months after “John Carter” opened, the Pixar sequel “Finding Dory” was announced with Stanton returning to the animation studio to direct. I asked Stanton if Disney leaned on him to direct the sequel. “That was something that I was producing from 2010,” Stanton said. “From 2010 to 2011, I was always in early, early development and going to produce somebody else to direct. And the second the movie came out, and I realized I didn’t have anything else to do, I was like, ‘Okay. I’m going to switch from my producer hat.’ I was always going to write it and produce it but I went from there to directing. I needed to go to a safe place where I was with family. And since it was already in motion, it seemed like the right move. But the only reactionary thing about that movie was me deciding to direct it versus just write it and produce it.” “Finding Dory” made more than $1 billion worldwide.

The Sequels That Never Were

Of course, the biggest tragedy was that more films weren’t made. When Stanton was still on Twitter, he shared logos for the second and third films in the series. He and Mark Andrews had already worked on the treatment and were about to send it to Chabon. Collins said that Stanton pitched her and Kitsch the second film in the series. Everyone was excited to work together again. “He pitched it to us too, which is why it’s so heartbreaking,” Collins said. “Because it was like, oh my God. Oh my God.”

With Disney losing the rights to the property in 2014, that pitch was lost for all time.

Or was it?

Andrew Stanton revealed to us his pitch for the “John Carter” sequel, “Gods of Mars”:

“I love the idea of you were going to open with the prologue. It was going to be that every movie had a different character saying the prologue. The first one is Willem, as Tars. The second one’s prologue narration was going to be Dejah. And it was going to give anybody that hadn’t seen the first movie a little precursor of the history that got you to this movie,” Stanton said. “Shorthand, interesting imagery, whether it was artwork or whatever. And then you were going to reveal she was telling it to her baby. And you were going to realize, Oh my God, it’s the child. It’s Carthoris, this child of Dejah Thoris and Carter. And that story she’s telling, she’s telling the story of the father that this child will never know.”

Stanton continued: “And then her dad, Ciarán Hinds’ character, Tardos Mors, said she’s been up too long, she’s tired, let her grandfather have a moment with the child and I’ll put her to bed. Then it was going to be revealed to be Matai Shang in shapeshifting mode. And he was going to steal the baby. And then it was going to go onto the opening credits. The next image after the opening credits was going to be Carter lying in his funeral suit in the middle of the desert, just looking like a dead body in a wake and just waking up.”

“Then he’s just going to take off his jacket like it was nothing and just start walking. And then eventually, just like out of ‘Lawrence of Arabia,’ way out in the horizon, is going to come a Thark on a thoat. And he’s going to surprise Carter by saying he knows exactly who he is and there’s been somebody looking for you. He brings him to a camp and it’s Kantos Kan which is James Purefoy, who’d been searching forever off of any river where this guy went. And so shocked that he’s found him. And then he says, ‘You have to get back now to heal him.’ And he gets back and you think it’s going to be a reunion, only to find out that there’s been some time between the prologue and the main credits.”

Stanton continued: “Now Dejah’s gone missing. She’s convinced that the Therns took their child and if Carter ever comes back, she went down the River Iss to try and find him. And then, like ‘Beneath the Planet of the Apes,’ it all takes place, everybody going into the earth to find out who’s really been controlling the whole planet. There’s a whole race down there that has been with high tech. Basically, it’s been a third world without anybody knowing it on the top of the surface and the first world’s been inside the whole time operating the air, the water, the everything to keep the world functioning. And yeah, I can keep going.” Stanton paused, then said: “But I’ve never told anybody the beginning of that. You can hold that dear.”

While all that world-building in “John Carter” ultimately bore no fruit in terms of tangible sequels from Stanton and Co., the film itself continues to endure a decade later despite its infamous reputation upon release.

Lynn Collins had a long journey to come to terms with the movie and her performance. But now she is embracing the unruly chaos of “John Carter.” “People started reaching out to me and expressing to me how much the movie changed their life, how much the character inspired them and motivated them. It’s posterity forever. I will die, and people will still be seeing this movie,” Collins said. “It’s huge. It’s a big deal. I ultimately think a movie that is that polarizing is good no matter what, because that’s what art is supposed to do. It’s supposed to provoke. It’s supposed to inspire. It’s supposed to catalyze. And I think that’s what this movie did.”