Beijing is trying to position itself as a peacemaker in Ukraine, not wanting to be seen as an accomplice to Putin’s aggression. But that is hardly credible while China continues to support Russia’s war aims, and will not condemn its leader’s invasion.

Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi told his Ukrainian counterpart that Beijing is concerned about the harm to civilians and “looks forward to China playing a role in realising a ceasefire”. He has repeated the Communist Party’s well-worn mantra about “the territorial integrity of all countries”. Ukraine has appealed to Beijing to exert its influence over Putin.

Yet Beijing has avoided even using the word ‘invasion’ and continues to echo Moscow’s talking points, that the conflict is the fault of Nato, Ukraine, the US – anybody apart from Putin. But if China cannot or will not see what is obvious to the rest of the world, what possible role can it play as a mediator – especially when so many of its actions suggest duplicity?

Hours after the invasion, Beijing lifted restrictions on wheat imports from Russia and is moving ahead with large-scale energy deals, including a new long-term gas contract with Gazprom. China also reaffirmed that its ultimate aim is to expand the use of its own currency, the yuan, in all trade settlements between the two countries.

In the short term these moves will cushion the blow of western sanctions on the Russian economy, and in effect underwrite Putin’s Ukrainian aggression. In the longer term it will serve the aims of both countries to achieve financial immunity by building an alternative payments system to that dominated by the US dollar.

China’s official media has also avoided calling Russia’s action an “invasion”, urging restraint on “all parties”. Social media has been less restrained, with nationalist bloggers, always allowed more leeway, cheering on Putin. The sentence “Nato still owes the Chinese people a debt of blood”, created by the state-run People’s Daily, became the top hashtag on social media platform Weibo. It refers to the 1999 accidental bombing by Nato of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade in which three people died, and was viewed more than a billion times.

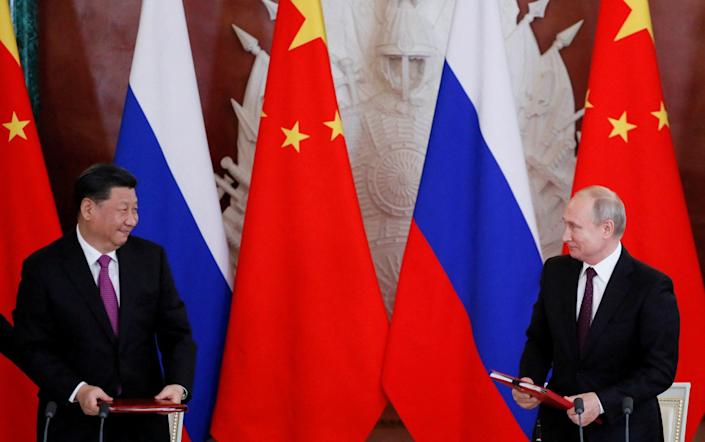

Putin and Chinese leader Xi Jinping are close personally – Xi once described Putin as his “best friend”. They made a big show of their partnership at a summit ahead of the Beijing Winter Olympics – Xi describing their friendship as having “no limits”. At that meeting, Xi for the first time explicitly endorsed Russia’s demand for an end to Nato expansion.

China does not have formal allies in the Western sense. It does not fit with Beijing’s sense of its own centrality, which is incompatible with an alliance system that might require obligations, commitments and a degree of equity. But it does have a hierarchy of partnerships, of which Russia sits at the top.

Joint military drills have become more frequent, more complex and more geographically spread. They have gone beyond symbolic shows of camaraderie, increasingly focused on co-ordinating command and control and enhancing battlefield interoperability. The Russians also have the combat experience that the People’s Liberation Army lacks, Russian troops having fought in wars in Georgia, Chechnya, Syria and of course Ukraine.

Historic animosities run deep – theirs is a marriage of convenience, but the relationship is no less dangerous for it. Putin and Xi share a deep paranoia about the West, and a loathing for western democracies. They are driven by historic grievance and victimhood, and a desire to overturn the western-led international order, against which Putin’s aggression represents a full-throated assault.

In other words, Xi shares Putin’s aims. But what of his means? And did the Chinese leaders know about the invasion of Ukraine in advance? The most plausible answer is that Xi was told by Putin in broad terms, but not in detail – or he hadn’t expected Putin to be quite so crude. Western intelligence reports suggest Xi did ask Putin to delay any action until after the Winter Olympics had finished, pointing to at least some degree of foreknowledge.

Xi now risks being tainted by association with the sheer barbarity of Moscow’s assault. He is left groping at a veneer of high-principled diplomacy, while unable to bring himself to condemn an act so self-evidently at odds with China’s supposed sacred principles of “non-interference”.

Xi will also have been taken aback by the strength and unity of the western response; as one observer recently put it, he would have preferred the invasion to have gone “uneventfully”. It is another article of faith in both Beijing and Moscow that the West is decaying, in decline and unable or unwilling to stand up for its principles. Yet western nations have been stirred by the shocking images coming out of Ukraine. Not only are Putin’s reckless actions galvanising western alliances, but the sanctions are broader and have more bite than many anticipated.

China will be watching closely the fate of Moscow’s ‘war chest’, its foreign currency and gold reserves held by Russia’s central bank. They have been targeted by the west in what may turn out to be the most effective of sanctions. The reserves now total around $630 billion, and had been seen by Russia as an important buffer. Yet many are held outside the country and could now be frozen. China holds $3.4 trillion of reserves and will now be rethinking how to resist western pressure in the event of a war over Taiwan.

The self-governing democratic island, which China claims as its own, is never far from the thoughts of Xi Jinping. As Putin’s tanks rolled into Ukraine, Taiwan strengthened its combat readiness and early warning systems. President Tsai Ing-wen warned that China might exploit the Ukraine conflict to step up pressure. Last weekend, the iconic Taipei 101 skyscraper was lit up in blue and yellow, the colours of the Ukrainian flag, in solidarity with Ukraine.

For some weeks now, the worst nightmare for strategists in Washington has been that Moscow and Beijing were co-ordinating their actions on the Ukrainian border and in the Taiwan Strait. At the very least it is widely accepted that Xi is watching the West’s reaction to Ukraine carefully as he calibrates his own strategy towards Taiwan. He may also be calculating that by supporting (or at least refraining from criticising) Russia’s actions in Ukraine, Putin may return the compliment over Taiwan in the future.

Beijing has been trying hard to discourage comparisons. It argues that Taiwan is not a sovereign state, that it has always been part of China – though this no more stands up to historic scrutiny than does Putin’s rambling questioning of Ukraine’s right to exist. Perhaps the most chilling parallel is that for Xi and Putin, the futures of Ukraine and Taiwan have nothing to do with the people who live there.

Russia is the junior partner in the relationship with China, and sanctions will reinforce this, giving Beijing enormous clout – particularly in negotiating energy deals. If Putin’s aggression forces western democracies to address their longer term reliance on Russian energy, then China will become its most important market by far – and Beijing will strike a hard bargain. Beijing may also be weighing the strategic advantage if the Ukraine crisis sucks US resources back to Europe and away from the Indo-Pacific.

Against that it must weigh the cost of guilt by association. For Beijing, it is not so much what Putin is doing as the fact his tools are so blunt and so visible to the world. The Chinese Communist Party has plenty of blood on its own hands, from the killing fields of Cambodia (Mao was Pol Pot’s biggest backer by far) to the deaths of millions during the Cultural Revolution and Great Leap Forward. It is a repressive state that uses multiple tools of coercion at home and abroad – but more cleverly deployed and not documented in real time in such chilling detail as we are now seeing in Ukraine.

There is now a real prospect of China getting caught up in the economic and political blowback over Ukraine, and the signs are that it is now recalibrating precisely where its interests lie. The irony is that the strength of western resolve over Ukraine, if it can be sustained, will benefit Taiwan, serving as a warning over what Xi could expect if he invaded.

Putin has put Beijing in a precarious position. The world was already growing wary of China – and the decisions Beijing makes over the coming days, its willingness to stand beside a pariah whose barbarism is provoking such global disgust, will shape global geo-politics for decades to come.

Ian Williams is a former foreign correspondent for Channel 4 News and NBC, and author of Every Breath You Take: China’s New Tyranny. To order from Telegraph Books for £16.99, call 0844 871 1515 or visit books.telegraph.co.uk