WASHINGTON (AP) — Russia’s expanding invasion of Ukraine has opened a new and perilous chapter in Joe Biden’s presidency, testing his aspirations to defend democracy on a global level and thrusting him into a long-term struggle to restore European security.

It’s a far different trajectory than he imagined when his administration began last year with the goals of countering China’s growing influence in the world and reinvesting at home as the United States tried to turn the page on a deadly pandemic.

Biden talked about forging a “stable and predictable” relationship with Russian President Vladimir Putin, a description that implied America’s focus could then be directed toward other, more pressing challenges.

Now he is confronted with the outbreak of the worst fighting in Europe since World War II. Although U.S. forces are not directly involved, the conflict is testing the limits of American power and Biden’s campaign assurances that he was well positioned to lead the country on the international stage.

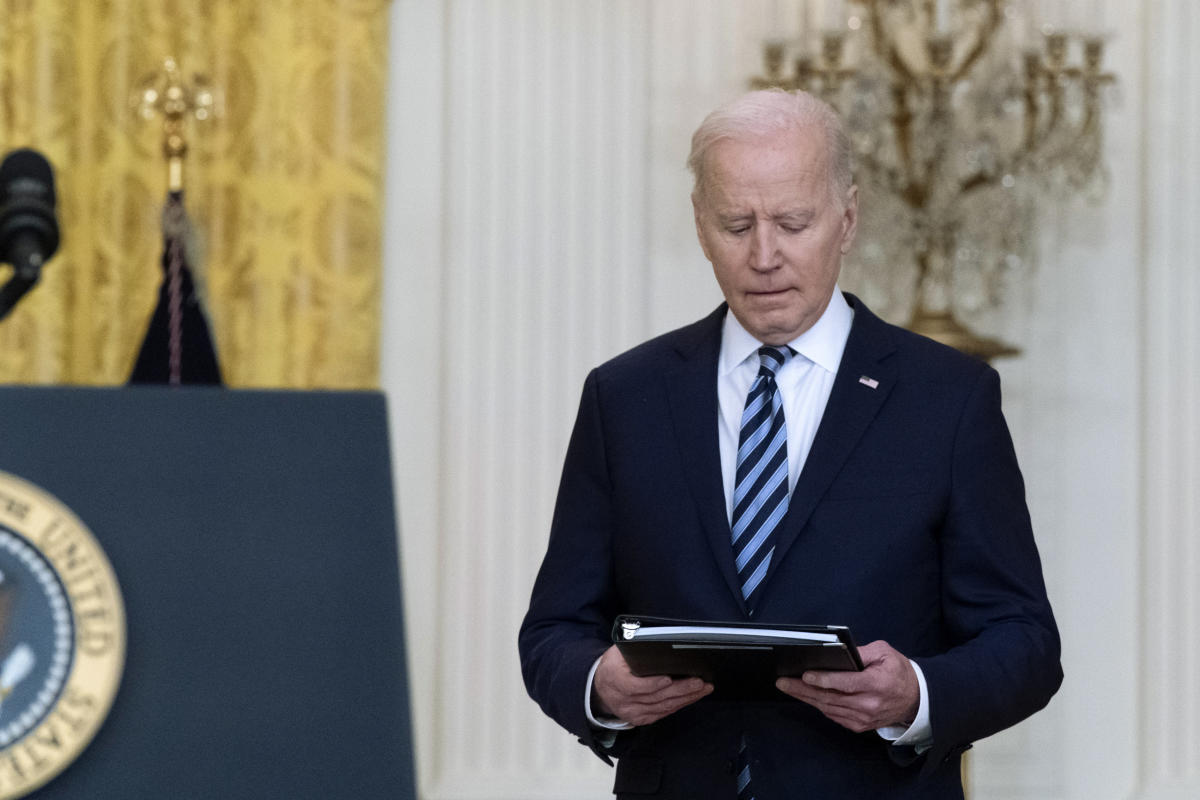

“We stand up to bullies,” Biden said Thursday at the White House. “We stand up for freedom. This is who we are.”

His efforts to prevent the invasion — by threatening sanctions and exposing Russian subterfuge — were not successful. U.S. officials believe Moscow plans to topple Ukraine’s democratically elected government and install a puppet regime in its place.

The grim scenario has forced Biden to shift toward complex plans to economically punish Russia and demonstrate the danger of an authoritarian government overturning a neighboring democracy.

“This is a fight that could take years,” said Timothy Naftali, a historian at New York University who has studied the U.S. presidency and the Soviet Union. “The future of Europe depends on the Kremlin paying a price for war crimes. If Putin gets away with this, what country is next?”

Biden announced additional sanctions Thursday, targeting Russian banks by freezing assets held in Western nations and limiting Moscow’s ability to import crucial technology such as semiconductors.

“We have purposely designed these sanctions to maximize a long-term impact on Russia and to minimize the impact on the United States and our allies,” Biden said.

What about the impact on him and his party?

The struggle will test American patience for playing a major role in foreign conflicts, even if U.S. troops are not themselves fighting. Biden already faces sagging approval ratings, and his domestic agenda, including education initiatives and climate programs, has stalled. Now the economic ripple effects from sanctions could contribute to inflation and higher gas prices at a time when the Democrats already are seen as likely to lose control of Congress in November’s midterm elections.

“I want to limit the pain the American people are feeling at the gas pump,” he said. “This is critical to me.”

Maintaining a united front with allies could also prove challenging. Although the White House has emphasized international solidarity, European nations usually have varying appetites for challenging Moscow and cutting themselves off from the financial largesse of its oligarchs. There’s dissension over whether to cut off Russia’s access to SWIFT, an international network that enables global bank transfers.

Biden predicted that Putin is “going to test the resolve of the West to see if we’ll stay together. And we will.”

Naftali said Biden, a politician with deep foreign policy experience who has embraced the traditional American role of anchoring the trans-Atlantic alliance, is “almost uniquely qualified to provide that leadership.”

“It recasts his presidency,” he said. “And this gives him an opportunity to demonstrate the arguments that you need a president who understands alliances and realizes you can’t go it alone.”

Strengthening international relationships was part of Biden’s pitch to voters when he was running against President Donald Trump, who scorned longstanding alliances in Europe.

And while Trump displayed coziness with Putin, Biden cast the Russian leader as an adversary in a global struggle between autocracy and democracy.

“Vladimir Putin wants to tell himself and anyone he can dupe into believing him that the liberal idea is obsolete – because he’s afraid of its power,” Biden said in a foreign policy speech during his presidential campaign.

On Thursday, he described Putin as someone with a “sinister vision for the future of our world,” a place where “nations take what they want by force.”

The conflict in Ukraine is only the most violent slice in a worldwide tug-of-war over democracy’s future. China has also held itself out as an alternative to Western liberalism, meaning Biden faces encroaching authoritarian powers on two fronts.

“The U.S. will have to manage both an aggressive and dangerous Russian dictator, on the one hand, and a more subtle but equally challenging Chinese regime,” said Eliot A. Cohen, a former State Department counselor who is now at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

A reminder of the challenges on the other side of the globe came Thursday when Taiwan said Chinese aircraft entered the island’s air defense zone.

Although such maneuvers have become routine in recent months, the latest was viewed warily as analysts wonder what lessons Chinese President Xi Jinping will take from the Ukraine crisis. China considers Taiwan, a self-governing island off the mainland’s coast, to be part of its territory.

There is also the potential for the war in Ukraine to snowball into an even greater crisis.

Fighting took place around Chernobyl, where the worst nuclear disaster in history took place in 1986. Disruptions at the site, which is now controlled by the Russians, could allow radioactive dust to escape and float over the area — or even neighboring countries.

“This is a declaration of war against the whole of Europe,” Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy tweeted of the Chernobyl attack.

Rep. Adam Kinzinger, R-Ill., suggested it “would certainly trigger Article 5,” the mutual defense commitment of NATO.

Already some NATO members in the region have invoked Article 4, which requires consultation when countries fear their territories are under threat. Ukraine itself is not a member of the alliance.

The Pentagon is deploying another 7,000 troops to Europe and shifting further east some assets that are already there, including attack helicopters and advanced fighter jets. Biden pledged the U.S. “will defend every inch of NATO territory with the full force of American power.”

Douglas Brinkley, a presidential historian at Rice University, said Biden “has to be ardent and tough but not let the situation unravel into World War III.”

“You don’t want Russian expansionism to metastasize,” he said. “This has to be quickly contained.”

The problem for Biden, he said, is “this can ring people’s Jimmy Carter bell,” referring to the former president’s struggle to respond to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979.

“Biden has to look at the politics of the situation,” he said. “The Republicans are going to paint him as the president who caused this.”

Trump himself, who remains influential in the Republican Party, has praised Putin as “pretty smart” for his handling of Ukraine.

Biden is already suffering from low support. Overall, 44% of Americans approve of his job as president, while 55% disapprove, according to a new poll from The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research.

An earlier AP-NORC poll conducted in January found that just 25% of Americans thought that “strong leader” was a phrase that described Biden extremely or very well.

Now Biden has both the challenge and the opportunity to prove his doubters wrong.

___

AP’s Hannah Fingerhut contributed to this report.

___

EDITOR’S NOTE — Chris Megerian has covered the White House and federal government for five years.